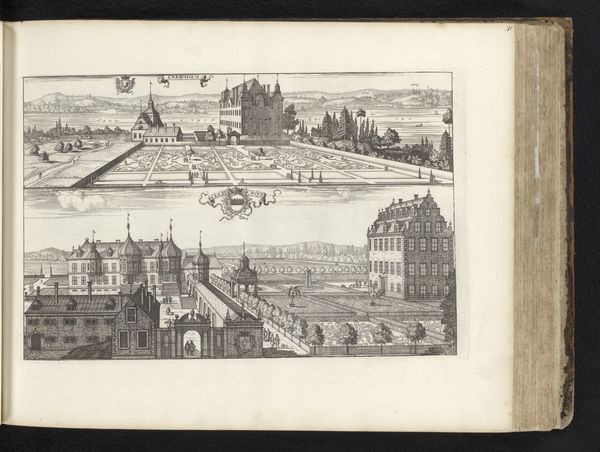

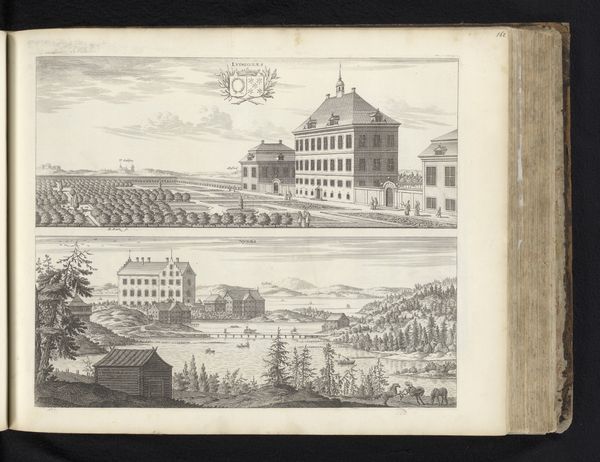

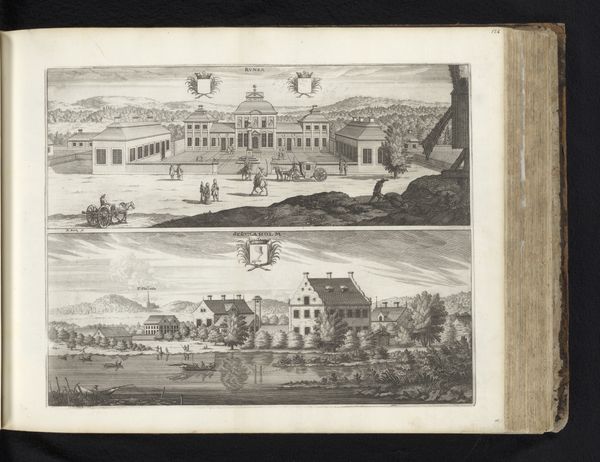

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

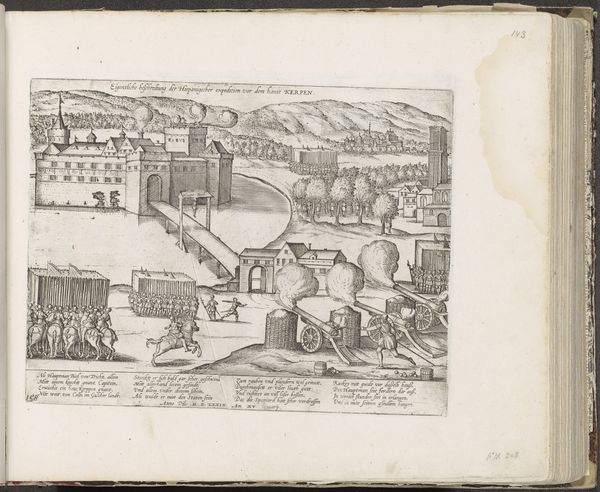

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 269 mm, width 336 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a print from 1695 by Erik Reitz, titled "Gezicht op slot Fiholm en landgoed Hanstavik," which translates to "View of Fiholm Castle and Hanstavik Estate." It's a fascinating depiction of two prominent estates. Editor: It’s interesting how it presents these properties as paired architectural statements, separated by… what feels like a significant social distance despite being on the same page, literally. The contrast in setting—water versus garden—also amplifies their different natures. Curator: Indeed. Prints like these played a crucial role in circulating images of power and status in 17th-century Sweden. This wasn't just about showcasing buildings; it was about communicating the influence and reach of the families who owned them. Think of them as early real estate brochures intended for an elite audience, but steeped in symbolic messaging. Editor: The engraving, especially the rendering of the water, is remarkably precise. Looking closely, one notices the emphasis on the built environment, overshadowing human figures, which is typical of that period. This print begs the question: how were the grounds managed? How much human labor was necessary to maintain the scale of these lavish landscapes and properties? Curator: Reitz, as an artist, likely had a patron. Consider that producing engravings required specific training and equipment; its consumption reinforces a power dynamic. Whose vision were these images meant to convey? What impact did it have on the working classes, or farmers? Editor: Examining the labor behind it reframes the appreciation. We acknowledge not only artistic skill but the real toil involved. This adds a dimension—a tangible human component. It is intriguing how such a meticulously crafted scene almost invisibilizes its makers. Curator: Ultimately, viewing this piece through that socio-political context shows its utility and influence. These kinds of cityscapes and architectural portraits served purposes far beyond pure aesthetic pleasure. They reinforced hierarchies and solidified certain perspectives. Editor: It goes to show how seemingly objective renderings always contain embedded values, impacting even our current gaze upon historical landscapes and properties.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.