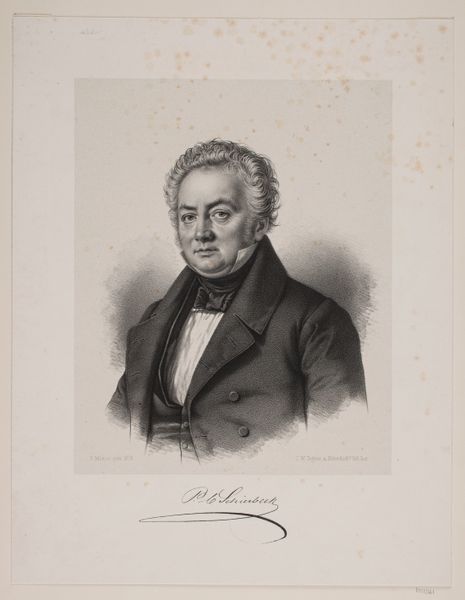

drawing, pen

#

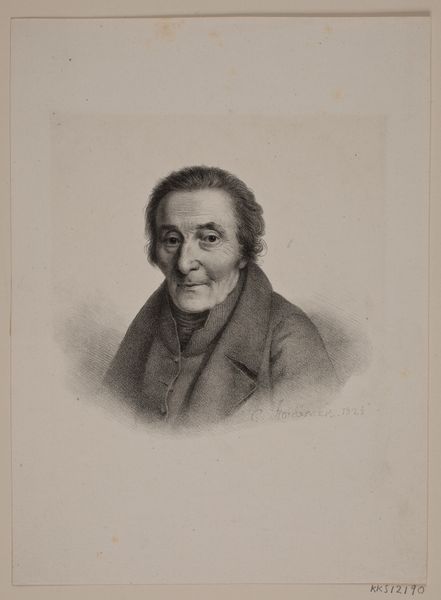

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

pencil drawing

#

pen

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 202 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece, I'm immediately struck by its starkness. The limited palette of grays gives it a solemn, almost austere quality. What do you make of it? Editor: I see the portrait of Gottfried Dietrich Schröder. Jean Augustin Daiwaille rendered this image sometime between 1809 and 1850. It's a Neoclassical drawing that seems to be pen and pencil on paper, currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. For me, it’s not only a picture, but the sum of the labor that went into creating it. Curator: I'm intrigued by that! I wonder, though, about the symbols embedded here. That confident gaze… the carefully draped fabric suggesting respectability and status… It feels almost archetypal of a certain class of men at that time. It has that familiar look. Editor: I'd be interested in researching the paper itself, see where Daiwaille might have acquired it. Mass production wasn’t what it is today. The labor involved is central to me, like how those tight strokes define the subject’s face. Also, what would it mean for such work to be rendered at that time? Did it reflect economic shifts? Curator: I wonder if Schröder had specific expectations for his depiction, wanting to project an image of wisdom, strength, or even piety. Notice that play of light and shadow to create those expressive lines. I wonder if he chose to hold still. Or whether Daiwaille captured some more fleeting essence, something unique about the subject’s character? Editor: Absolutely. To add to your perspective, I notice there are limited mid-tones; they seem either quite pale, or dense in tonality. A fascinating aspect that could derive from some form of scarcity? Or, an abundance of tools which create this sharp contrast? I see it not just as his individual artistic choice, but a decision entangled with available resources, artistic markets and material culture. Curator: All compelling. In the end, this portrait whispers secrets of a man, a society, and a moment frozen in time. Editor: Indeed, it prompts us to consider not just *who* is depicted, but *how* the very act of depiction occurred, and how that labor tells a story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.