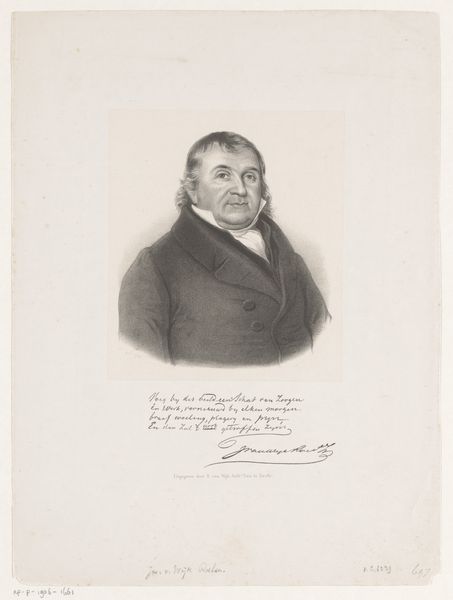

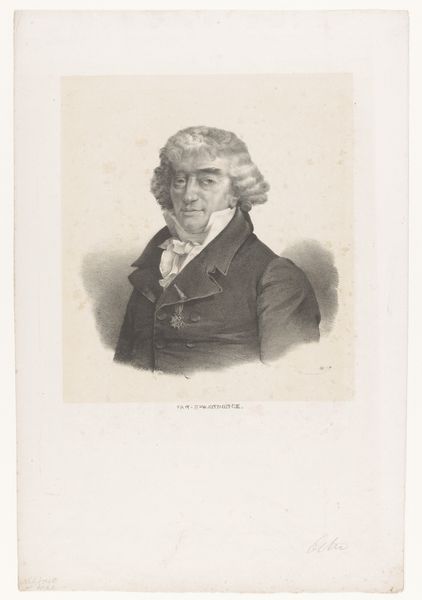

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 311 mm, width 243 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us hangs "Portrait of Frédéric Théodore Faber," a print executed in 1822, currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. Its medium is engraving. What's your immediate take on this piece? Editor: Stark, isn't it? The lines are so deliberate, almost clinical. There's a seriousness to the subject that feels very… proper. Curator: Indeed. Engravings like this played a crucial role in disseminating images widely, making portraiture more accessible to a broader public. Think about the labour involved – the meticulous cutting of the plate, each line representing a conscious decision. Editor: The linearity emphasizes form; you can trace the structure of his face, the cut of his coat. The artist really plays with light and shadow to give dimension to what would otherwise be quite flat. This close attention given to volume and chiaroscuro almost flattens it; paradoxically there are some flattened areas. Curator: Precisely. This connects to the prevailing Neoclassical ideals, championing reason, order and idealised form during the rise of industrial methods for art production and commercial distribution. Editor: Do you see any sort of connection between the choice of material in relation to the subject itself, and the moment when it was created? Curator: I do. The rise of prints reflected the shift towards more democratic art forms and affordability. It’s a testament to art's adaptability within changing economic structures. Prints are objects produced at multiple copies, a great method for promoting certain imagery through large, socially expanded circles. Editor: But what does the technique and style then tell us about Faber as a man? Does the artist flatter him with this technique or reveal him? The cool detachment is striking, considering portraits usually seek intimacy. Curator: Perhaps it mirrors the man's status or profession within a society that demanded such visual conformity and decorum. He may want to suggest refinement with this portrait. Editor: Maybe. What resonates is that this image transcends the personal to offer us a glimpse into social and economic climates. Curator: Ultimately, the image is shaped by a system where even personal representation cannot fully detach from labour and the means of mechanical reproduction. Editor: And visually, it offers a certain compelling restraint.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.