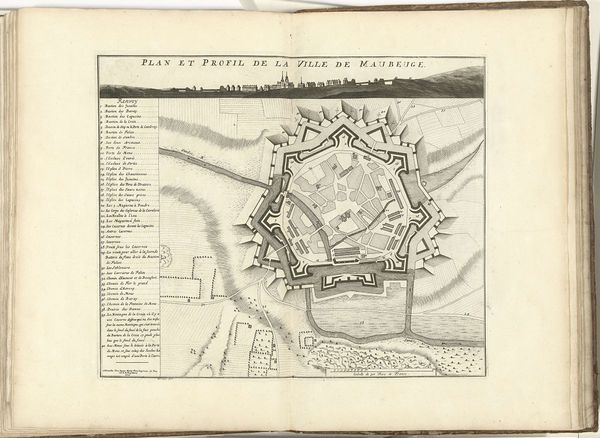

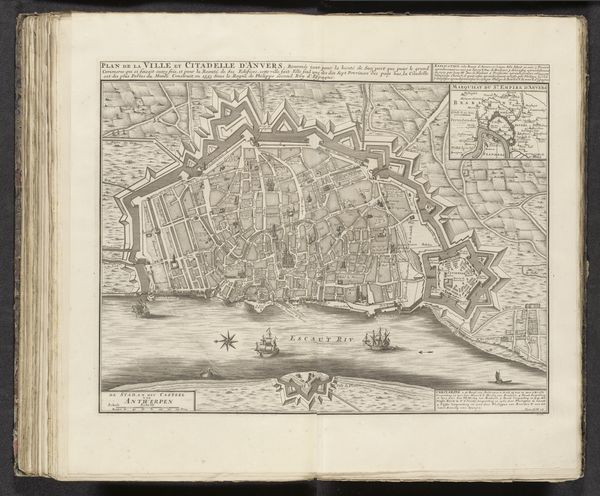

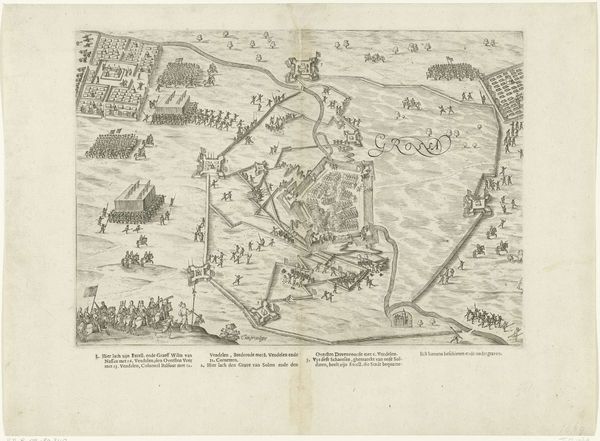

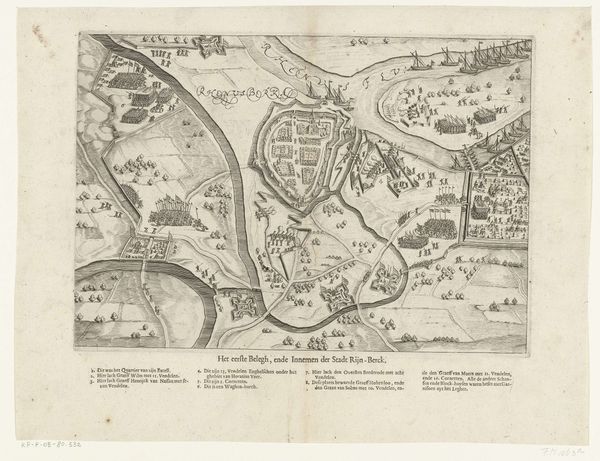

Titelpagina van het pamflet: Journael ofte Dach-register van 't principaelste in Vlaenderen geschiet, sedert den 25 april tot den 15 September 1604, so vant inneme des Schansen, schermutsingen, als ooc van 't geweldich belegh en overgaen van Sluys, 1604 1604

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

early-renaissance

#

engraving

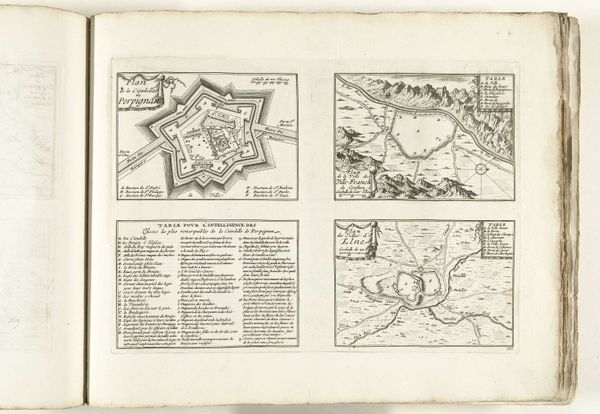

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 144 mm, height 205 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

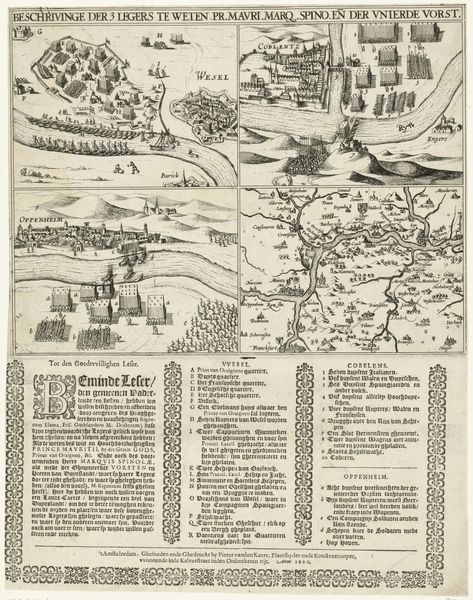

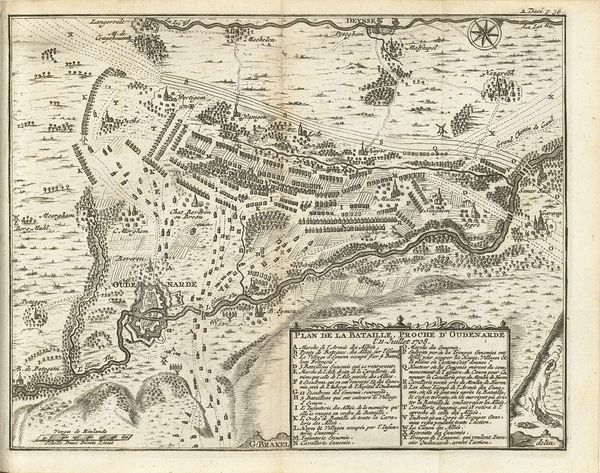

Curator: Let’s begin by focusing on this incredibly detailed engraving titled "Titelpagina van het pamflet: Journael ofte Dach-register van 't principaelste in Vlaenderen geschiet…," created in 1604. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate impression is that it’s a surprisingly clear, almost diagrammatic rendering. The black and white starkness emphasizes a kind of brutal functionality. This wasn’t created to inspire beauty, it seems, but rather to communicate strategic information. Curator: Precisely. The engraving functions as the title page for a pamphlet detailing events in Flanders during the period of April to September 1604, focusing on sieges, skirmishes, and the siege of Sluys, documenting the military actions led by Spinola. The list on the left and top is really valuable because it highlights significant locations. Editor: I see the connection now—the list as an index of places depicted materially on the map. This kind of production really straddles the line between craft and documentation. Consider the labor invested, the materials selected, the deliberate decisions behind carving these tiny geographical details... What does it tell us about early printing practices and the relationship between disseminating information and manufacturing objects at this time? Curator: Absolutely. It underscores the intersection of politics and the printed image in the Early Renaissance. The map isn't just about topography; it is a symbolic representation of power, control, and conflict during a politically tumultuous time. The pamphlet situates these events within the broader context of the Dutch Revolt. Editor: So, by scrutinizing this pamphlet not merely as art but as a product of its time—we expose complex material and labor relationships involved. Looking at the production process makes the work’s explicit social purposes as an activist communication device really stand out. Curator: I agree. Approaching this artwork allows us to view early print media as essential, multifaceted objects capable of documenting lived experience as well as participating actively within the world as disseminators of cultural, and historical, understanding. Editor: Seeing the pamphlet as a material witness to historical events forces us to contend with the social contexts of production, revealing the intrinsic relationships between objects, information, and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.