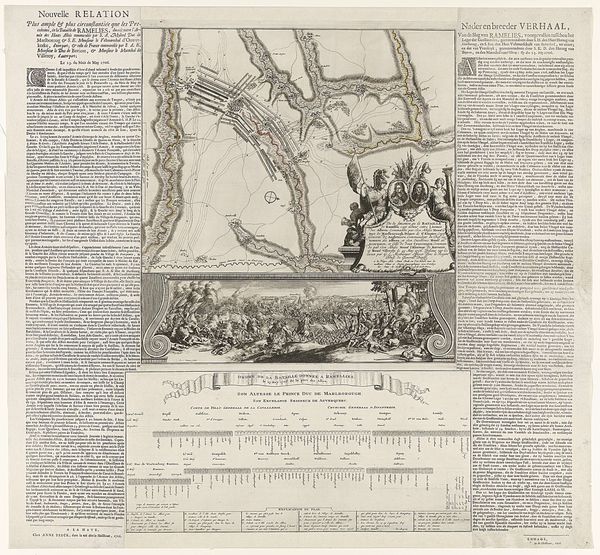

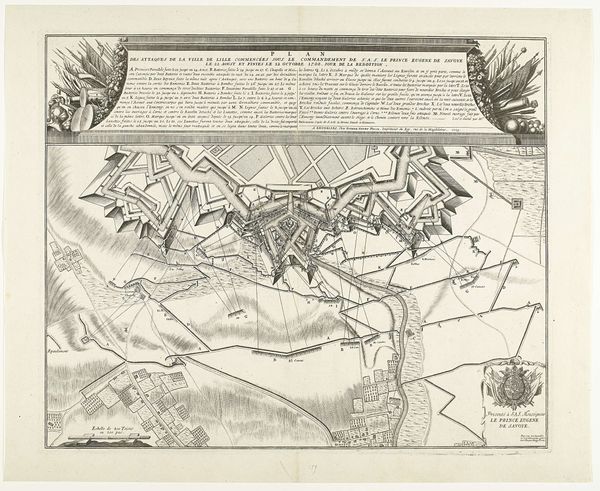

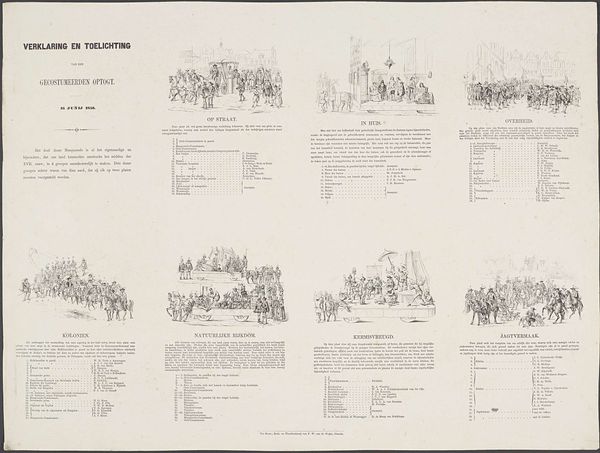

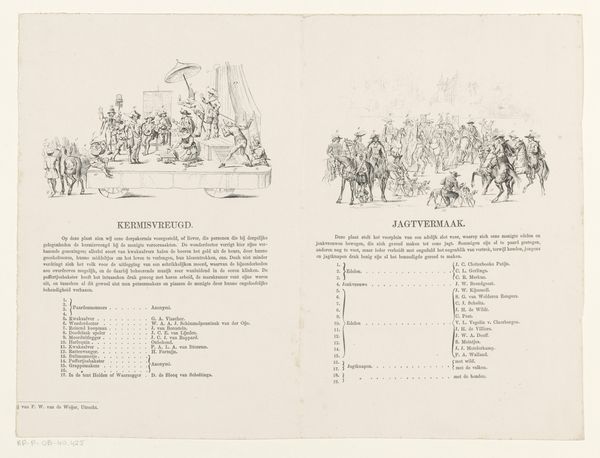

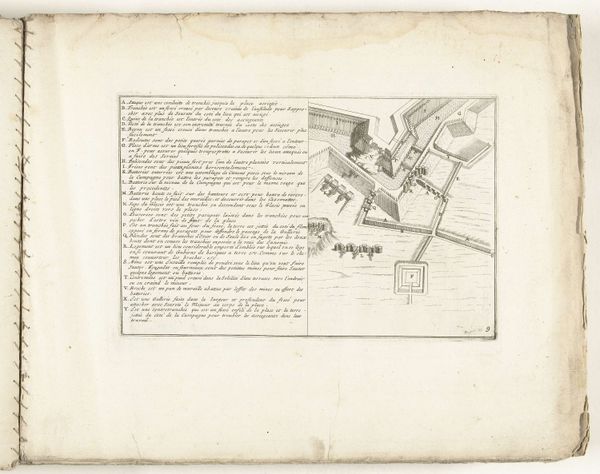

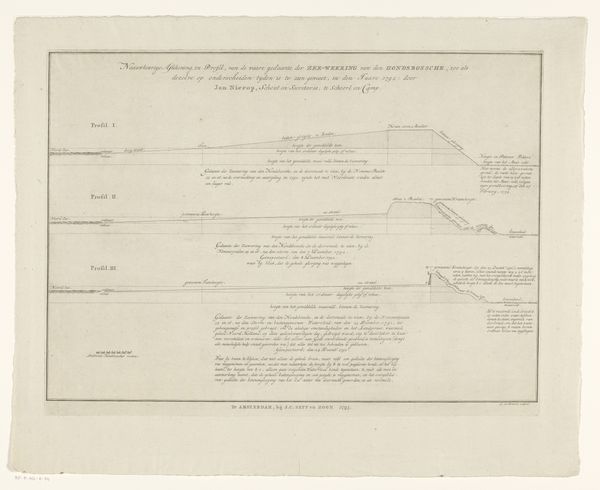

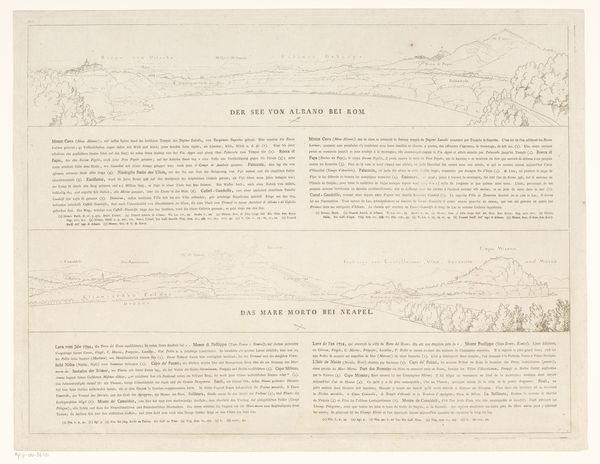

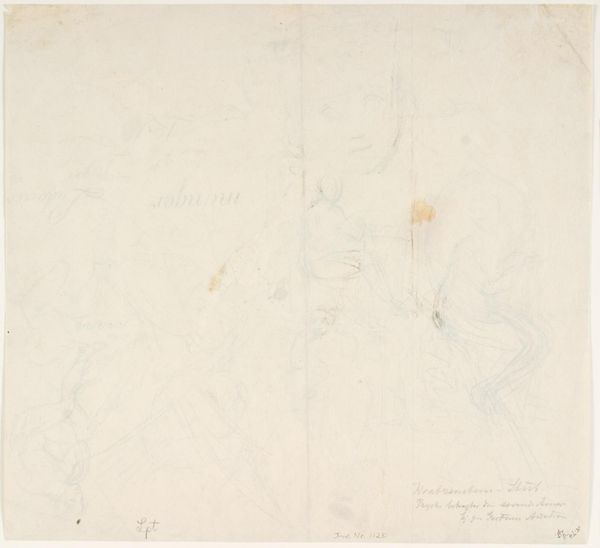

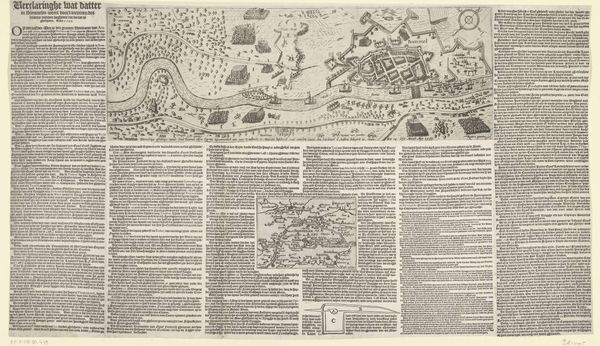

drawing, print, etching, paper, engraving

portrait

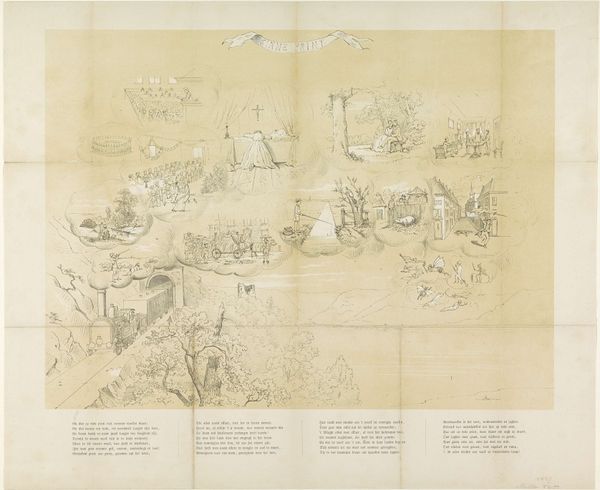

drawing

etching

paper

romanticism

history-painting

engraving

Dimensions: height 470 mm, width 514 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have John Burnet's "Key to the Portraits in the Battle of Waterloo," likely from 1819. It’s a print, an etching really, showing portraits and a battle scene in the background. I'm struck by how it serves as both an informational guide and a piece of art. How should we interpret a piece like this that blends artistry and historical record? Curator: That's a crucial observation. Think about it: Burnet created this "key" in the wake of a pivotal moment in European history. Waterloo wasn't just a battle; it was a moment intensely politicized, mythologized, and used to shape national identity. An image like this reinforces certain power structures by depicting key figures, the victors, primarily, casting them as heroes in a readily reproducible format. Who gets a portrait and why? How might this affect public opinion and the long-term memory of the battle? Editor: So it’s not just a neutral guide; it actively participates in constructing a particular narrative of Waterloo. Are the depicted figures idealized? Is this common for this type of historical print? Curator: Exactly. While there might be some effort toward likeness, these portraits also convey authority and respectability. Consider who commissioned and consumed these images. Were they intended for a broad public or a more elite audience? This helps us understand its role in reinforcing social hierarchies. How does the text accompanying the portraits support that? Editor: It looks like excerpts from Wellington’s dispatch... So, official documentation alongside glorified portraits... It paints a clear, favorable picture of the British victory, doesn't it? I now see how a seemingly straightforward guide becomes a powerful piece of propaganda. Curator: Precisely. Art is rarely neutral, especially when it intersects with historical events. Reflecting on the role of art in shaping perceptions of events can prompt critical dialogues around its influence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.