!["VIII Station", achtste station in de lijdensweg van Christus [?], Jeruzalem [?], Palestina [?] by Maison Bonfils](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzViMmJkMWQzLTc2NTUtNGZlNS05MTE5LTU1OTU5MzNkNDhlMS81YjJiZDFkMy03NjU1LTRmZTUtOTExOS01NTk1OTMzZDQ4ZTFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

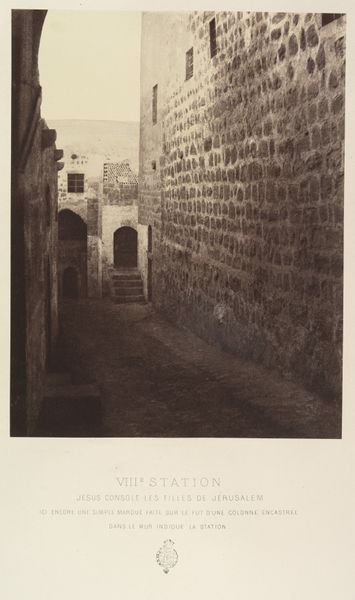

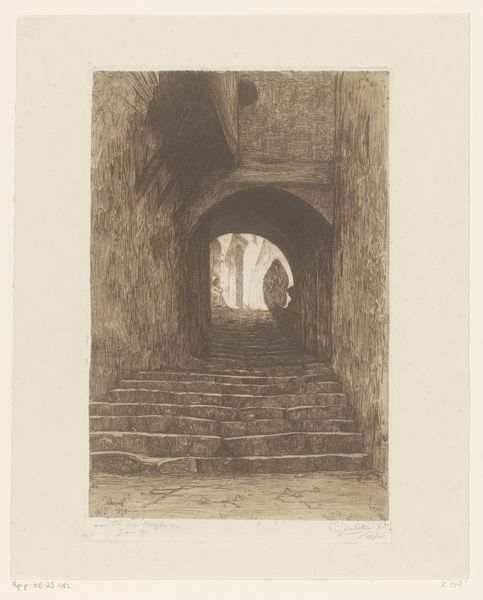

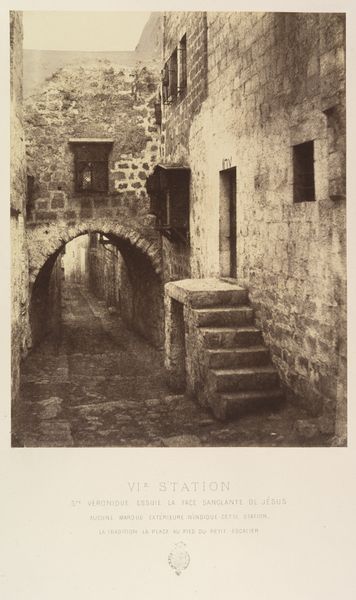

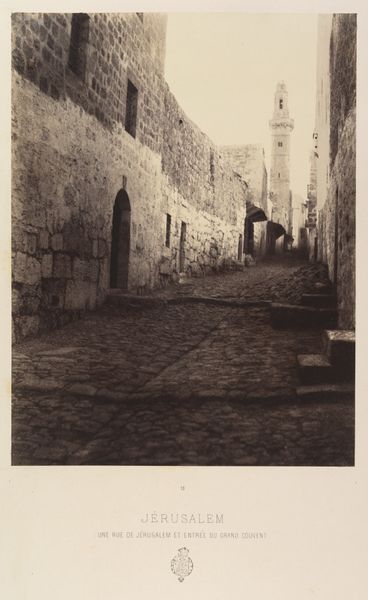

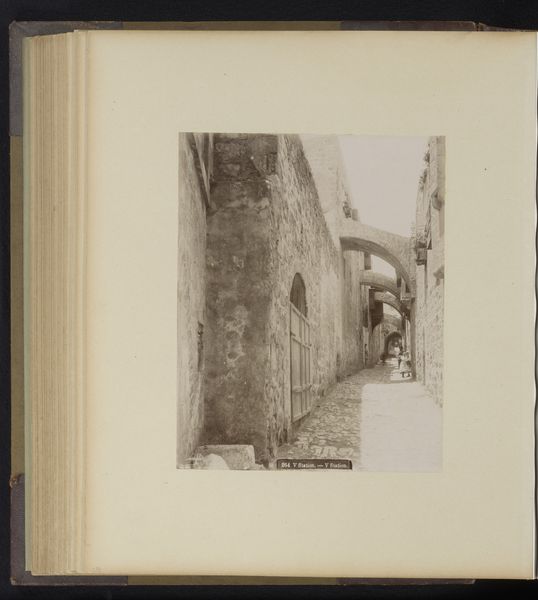

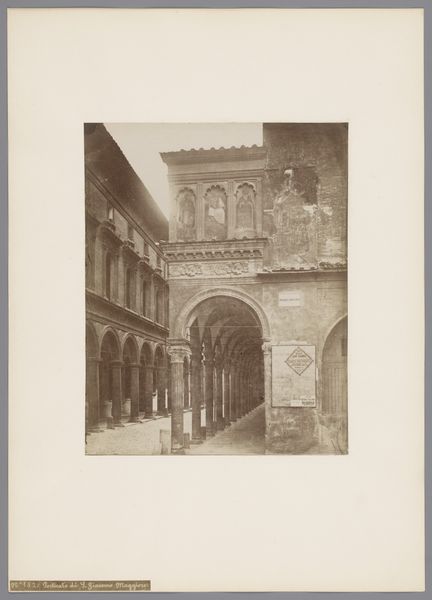

"VIII Station", achtste station in de lijdensweg van Christus [?], Jeruzalem [?], Palestina [?] c. 1880 - 1900

0:00

0:00

maisonbonfils

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photo of handprinted image

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

remaining negative space

#

monochrome

Dimensions: height 277 mm, width 218 mm, height 394 mm, width 344 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This photograph, titled "VIII Station," is attributed to Maison Bonfils and thought to have been taken between 1880 and 1900. It's a gelatin-silver print, showcasing a street scene in what's believed to be Jerusalem, Palestine, and it depicts the eighth station of the Via Dolorosa. Editor: It strikes me as claustrophobic at first glance, a long view of the stone corridor, but the depth of the light at the tunnel's far end brings relief and guides your eye. The material reality of those aged stone walls and cobblestones feels heavy with history. Curator: Precisely. The albumen print, hand-printed on location, is an example of early photography’s role in documenting and, indeed, constructing orientalist perceptions of the Middle East for a European audience. Think about the labour involved – the physical presence, the darkroom tents. It was a meticulous, resource-intensive undertaking. Editor: That’s where my mind goes too – not just the immediate view but what this represents within power structures. How does this imagery circulate and perpetuate colonial narratives? It portrays a specific version of Jerusalem to consumers back home, framing a cultural experience packaged for the Western gaze, effectively exoticizing local life and potentially feeding into biases. Curator: Good point. One can speculate as to why this route and not another was captured. Were tourists, for example, funnelled through specific routes for control? The tangible print reveals a specific encounter, shaped by decisions about process, location and material means. Editor: The visual encoding reinforces stereotypes. The narrow alleyways signify, in some interpretations, the timeless "otherness" of this location—separate from modern advancements and frozen within colonial fantasies. What about local responses or acts of resistance towards these pervasive images and the broader colonial machine they represented? Curator: Unfortunately, access to information is limited. Yet examining the material existence allows analysis of circulation, value and ultimately consumption back home, highlighting a crucial link in understanding socio-economic inequalities in our history. Editor: Agreed. Ultimately, this image isn't merely a photograph; it’s a carefully manufactured commodity intertwined with socio-political currents, serving the orientalist market's hunger. We must consider that and also consider its present-day circulation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.