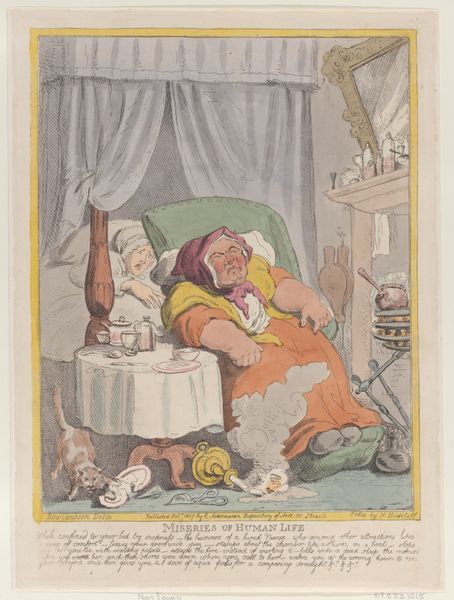

drawing, coloured-pencil, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

# print

#

etching

#

caricature

#

caricature

#

paper

#

coloured pencil

#

romanticism

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 208 × 257 mm (image); 208 × 257 mm (plate); 213 × 263 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have George Cruikshank's etching and colored pencil work, "The Cholic," possibly from 1819. Editor: My initial impression is one of intense agony and a touch of the grotesque, but presented in a rather… refined way. It's like a nightmare served on fine china. Curator: A keen observation. Cruikshank, known for his social caricatures, utilizes the print medium to broaden its reach. Consider how the etching, alongside hand-applied color, would allow for a more democratized distribution of this potent imagery. It critiques, through visual means, the social realities concerning health and the body in Romantic era society. Editor: Precisely. Note the devils tormenting the poor woman, and that beam constricting her waist. This vividly depicts physical distress, and I cannot ignore the artistic and cultural memory relating such bodily affliction to symbolic 'devils.' Do you see hints of how anxieties might coalesce in one’s own perception, externalized in these demonic torturers? Curator: Indeed. Also, don’t miss the satire implicit in rendering the material excesses—the plush chaise lounge, her fine gown—in the same frame as this visceral display of suffering. The production of such items necessitates social disparity, perhaps insinuating the source of her "cholic." The labor underpinning the material comfort starkly contrasts with the lady's personal torment. Editor: Symbolically, though, consider her constricted waist. Her suffering could also speak to constraints on women of the period: those of dress, and, more metaphorically, the pressures placed on the feminine form both physically and socially. The ‘devils,’ then, may symbolize anxieties related to restrictive societal norms. Curator: I’m especially drawn to how the materials themselves—etching and color—mediate that tension, enabling Cruikshank to render visible and tangible the societal strains manifesting as individual affliction. Even in our looking, it urges a critique of its means, not just of its symbols. Editor: Very well observed! And to me, the longevity of such symbols points towards cultural undercurrents that linger still. In short, it is always important to contemplate the meaning but, equally so, our connection to it as the viewer. Curator: Absolutely. Thinking about both production and representation deepens our viewing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.