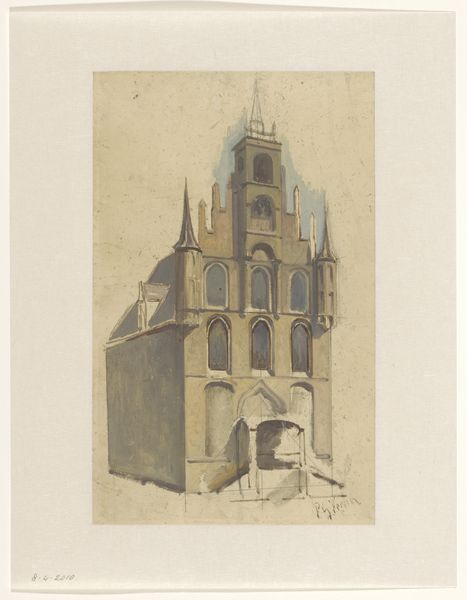

painting, watercolor

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

watercolor

#

realism

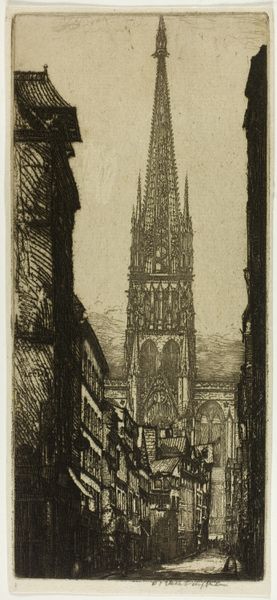

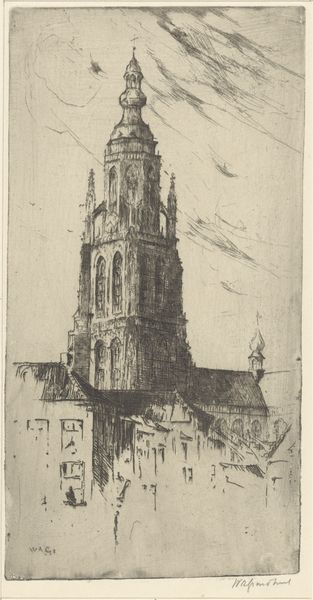

Dimensions: height 137 mm, width 74 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

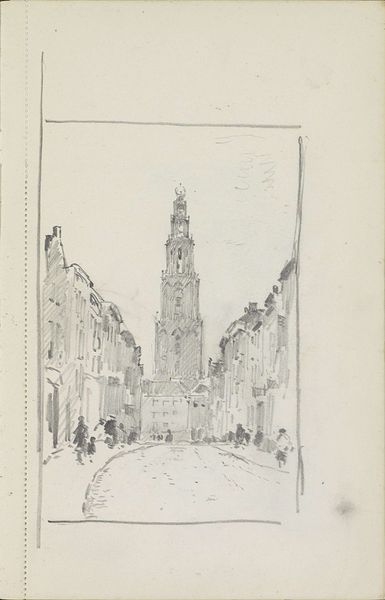

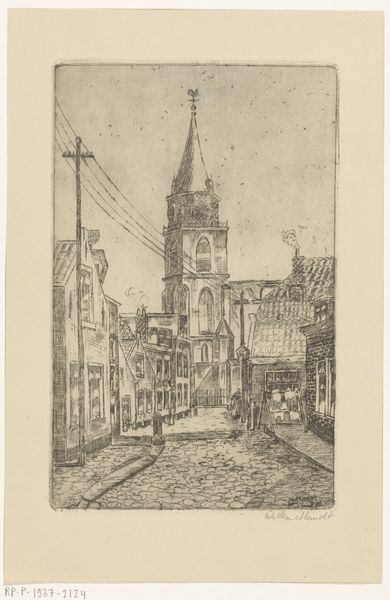

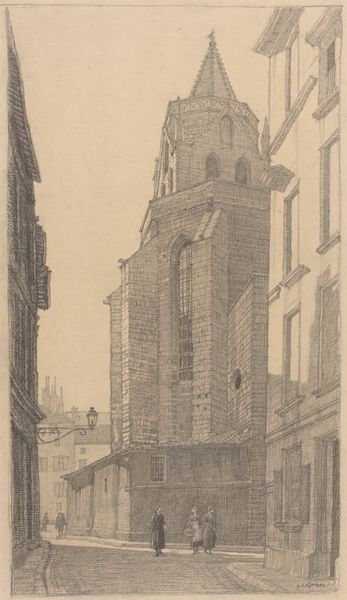

Editor: This is "Straatgezicht met doorkijk op de Grote Kerk te Breda," a watercolor by Carel Jacobus Behr, painted in 1832. The towering church, seen through the street, creates such a striking sense of perspective. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see a deliberate choice to frame power, both ecclesiastical and societal. The church dominates, certainly, but observe how the architecture of everyday life hems in the ordinary people populating the street. Think about the religious and political landscape of 1832 Netherlands; Behr’s choice of perspective seems loaded with commentary. What social classes do you imagine inhabited the buildings that frame this view? Editor: Well, the buildings on either side seem like standard housing, suggesting maybe a mix of merchants and working-class families? Curator: Precisely. And considering the context, do you believe access to or influence within the church was distributed equitably across those classes? Behr presents a clear visual hierarchy that mirrored real-world social structures, revealing not just a landscape, but a system of power. Editor: I hadn’t considered the social dynamics so explicitly. It's easy to get lost in the artistic style without thinking about the societal context. Curator: Indeed, Behr was working within the stylistic framework of both Romanticism and Realism. His attention to architectural detail serves Realism, but the overall atmospheric quality leans Romantic. Can you see how both of these influences impact your perception of the church and the townspeople? Editor: Yes, the detail brings a sense of truth to the scene, but the light and soft color palette almost idealize it. So it presents reality but perhaps with a certain bias? Curator: Exactly. And what happens when we see that bias? How does the very act of image-making shape our understanding of the world? Editor: That's a powerful way to consider historical art. It’s not just about aesthetics; it's about uncovering hidden messages. Curator: Precisely. And questioning them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.