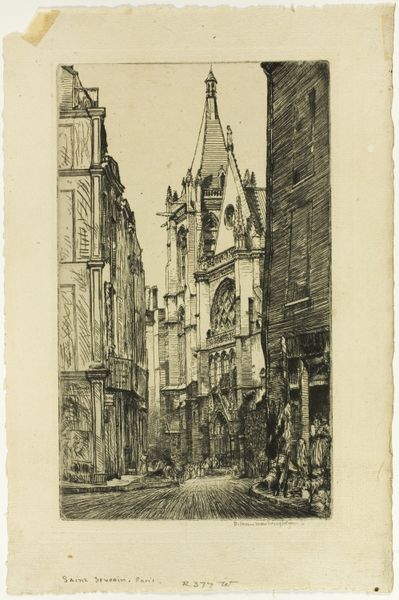

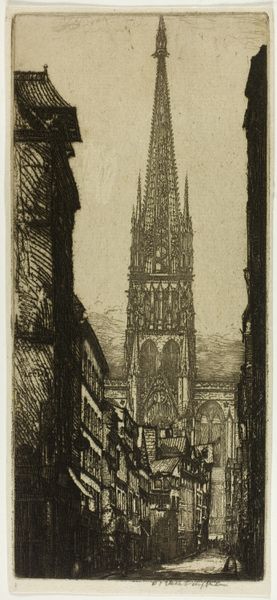

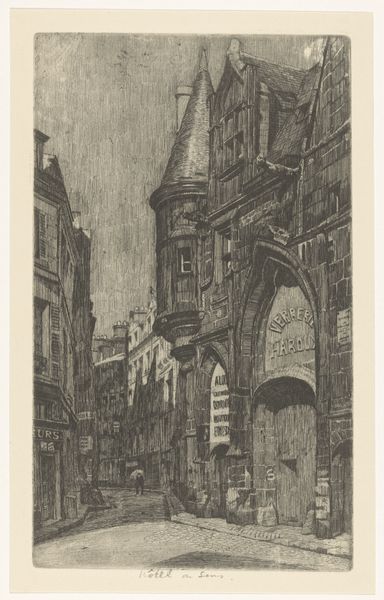

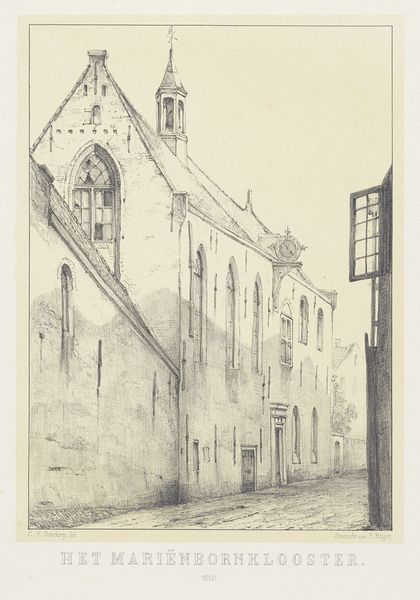

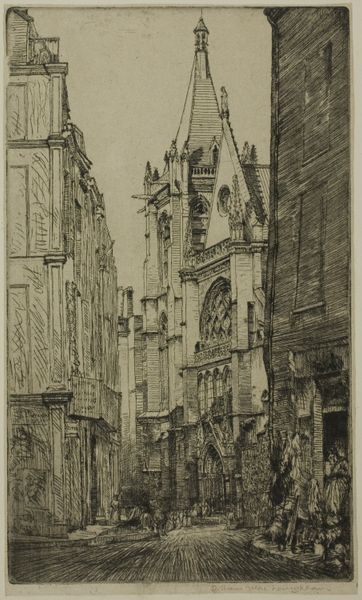

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

france

#

cityscape

#

realism

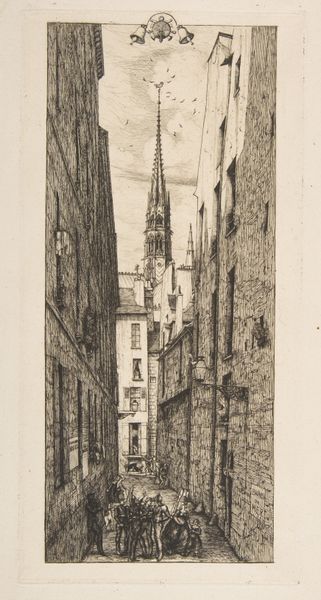

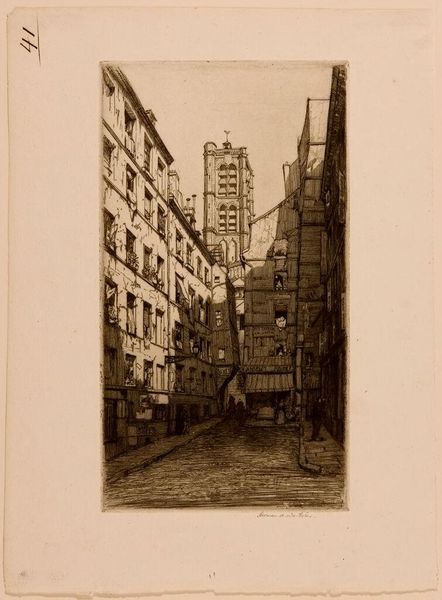

Dimensions: 280 × 120 mm (image); 298 × 147 mm (plate); 336 × 159 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us we have Charles Meryon's 1862 etching, "Rue des Chantres, Paris," currently residing here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Oh, what a deliciously cramped little world. It feels…oppressive, in the most elegant way possible. The perspective just slams you into this narrow street, and that gothic spire towering in the background—it’s almost mocking. Curator: I find the architectural detail astonishing, particularly given that etching relies so heavily on line work. You really get a sense of the age and density of Parisian construction, how the city kind of…grew in on itself. The choice of etching captures the textural details. Editor: Textural is right. You can practically feel the grit of those stones beneath your fingers, smell the dampness rising from the ground. Look at the way Meryon’s rendered those figures huddled in the foreground—they seem almost secondary to the architecture. What materials did he use, anyway? Was the paper specially sourced? Curator: Meryon, from what records indicate, employed a traditional copper plate for the etching process, and it was printed on paper—the exact sourcing isn’t clearly identified in museum records, though given the period, it was likely a good quality, locally-produced stock. Knowing Meryon, every aspect was deliberate, even his choice of printing paper. His dedication to his craft speaks to a man absorbed, and the amount of labor clearly went into these minute depictions, where his mind saw so much significance and story. Editor: Exactly! Because who are these figures? What are they doing? Are they laborers, beggars, dissidents plotting some anti-establishment uprising? They’re clearly engaged in commerce. It’s fascinating how Meryon has elevated a mundane street scene into something so loaded with implied narrative and class anxiety. Are we seeing, perhaps, an elegy of the Parisian underbelly? Curator: That's a beautiful way to describe it. I'm consistently struck by Meryon's capacity to draw the eye skyward, to the grand scale, when so many other works of this kind would keep the gaze level to the immediate drama on the ground. Editor: I suppose for me it speaks of both social stratifications, in this instance: the church above and the bustle below; a commentary about work; about access; about all that defines this singular view that Meryon made so accessible. Curator: It feels strangely prescient, don't you think? An artist working during an era of massive urbanization, anticipating a world even more defined by these compressed urban spaces, while leaving traces of how the city fabric was made? Editor: Absolutely. It’s a dark poem etched in ink and paper—a testament to the power of material and memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.