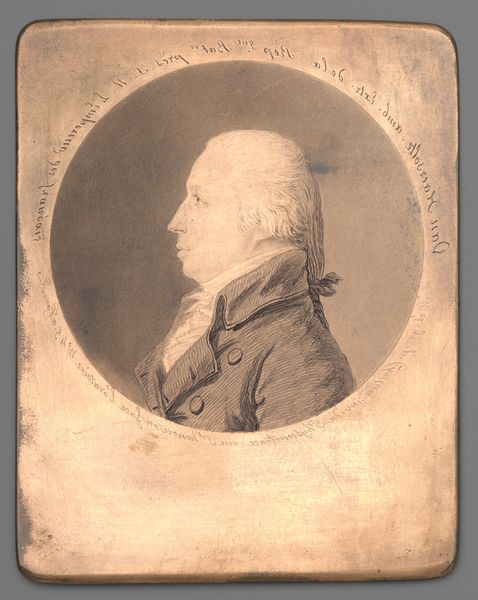

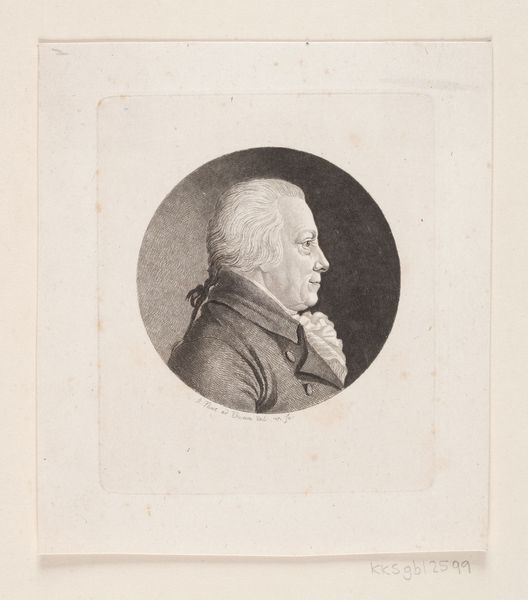

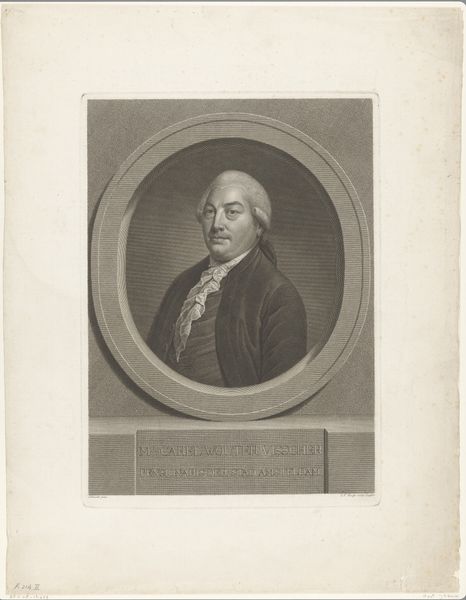

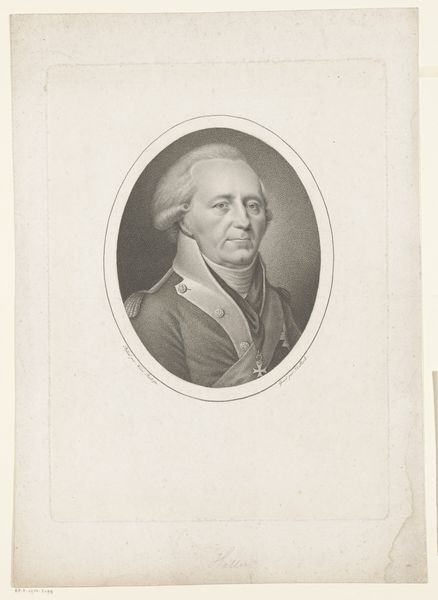

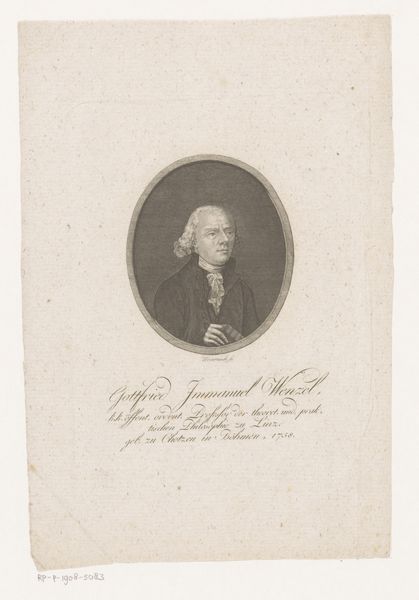

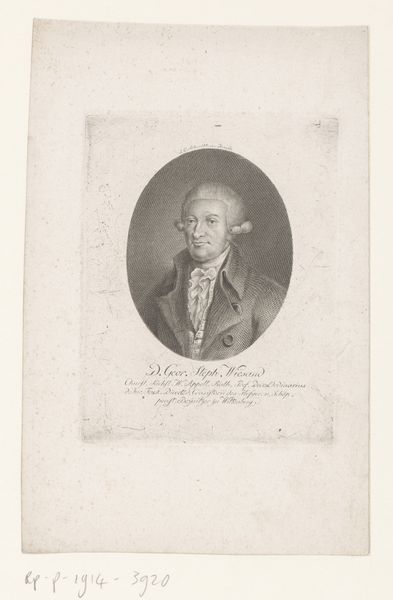

Portrait of a man in uniform to right 1786 - 1799

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 3 in. × 3 1/16 in. (7.6 × 7.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The piece before us is a late 18th-century portrait—more precisely, an engraving by Gilles Louis Chrétien, titled "Portrait of a man in uniform to right," placing it somewhere between 1786 and 1799. It exemplifies the Neoclassical style so prevalent at the time. Editor: It's austere, isn't it? That sharp profile cut against the stark white, almost… Roman in its severity. Gives me the shivers, thinking about powdered wigs and revolutions. There's a crispness in the line that feels very detached. Curator: Absolutely. Chrétien was actually quite the innovator, pioneering a mechanical engraving technique called the physionotrace, which allowed for accurate and reproducible portraits. This was significant in democratizing access to portraiture. It created multiple portraits to be distributed among networks, social circles. Editor: Ah, so it's the 18th-century equivalent of the selfie! Makes me wonder who this man in uniform was, and who might have received copies of this portrait. Did it serve some specific purpose for him? His clothing seems important. Curator: The uniform signifies his belonging to a particular regiment, an elite class. These portraits weren't just about likeness; they were about status, about cementing one's place within the social hierarchy. Chrétien's clients often included members of the aristocracy, military figures, or notable bourgeois. Editor: So, image as power… it tracks! I wonder, looking at it closely, if the accuracy granted by this new machine also unintentionally strips away some of the soul. It is accurate, sure, but a little… empty? It almost seems too literal. No poetry! Curator: I see your point. Perhaps the technical precision prioritized the factual over the emotive, reflecting the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason and empiricism. The revolution then turned the public's access to reproducible portraiture, which had mostly included the noble, into an emblem of propaganda. Editor: Yes! Despite, or perhaps because of the lack of personal feeling, the print encapsulates this important moment of time. Thank you for bringing this history to light! Curator: My pleasure. It is a small picture with echoes of revolution, isn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.