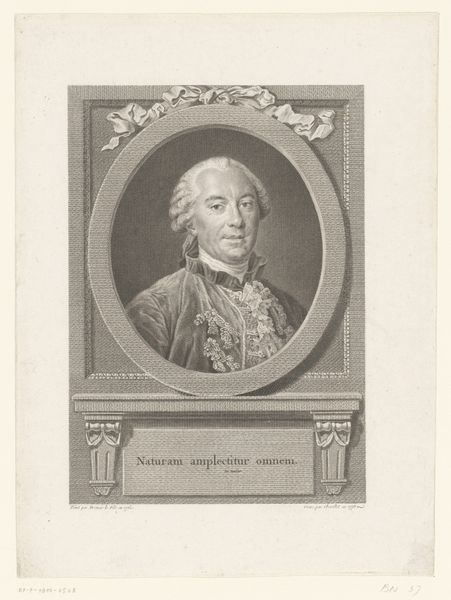

graphite, engraving

#

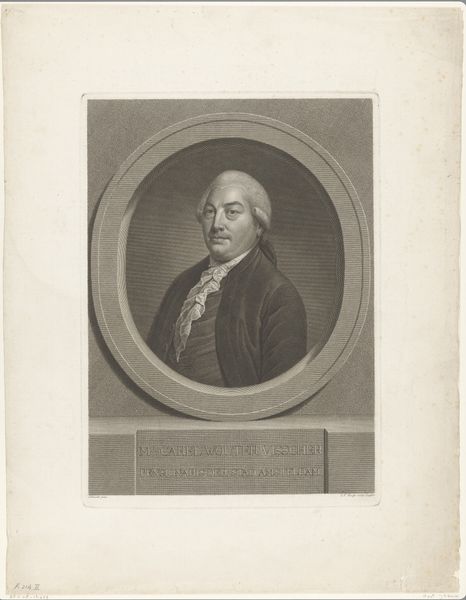

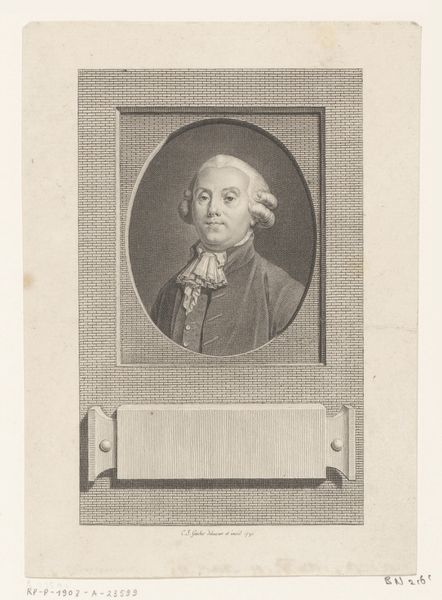

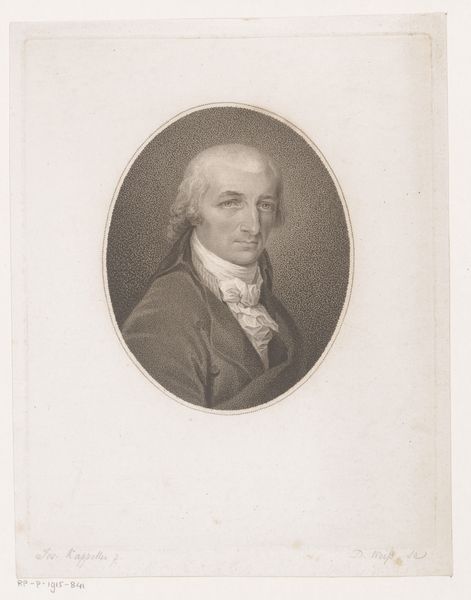

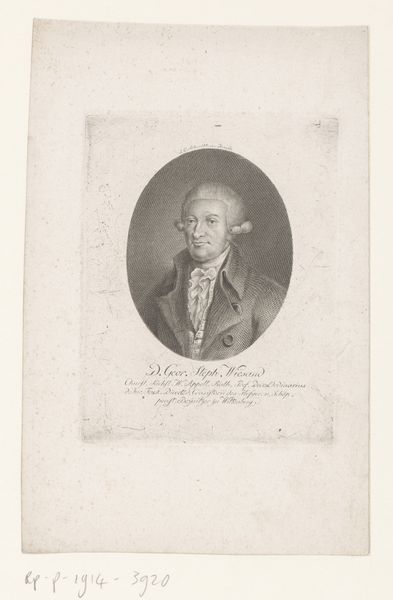

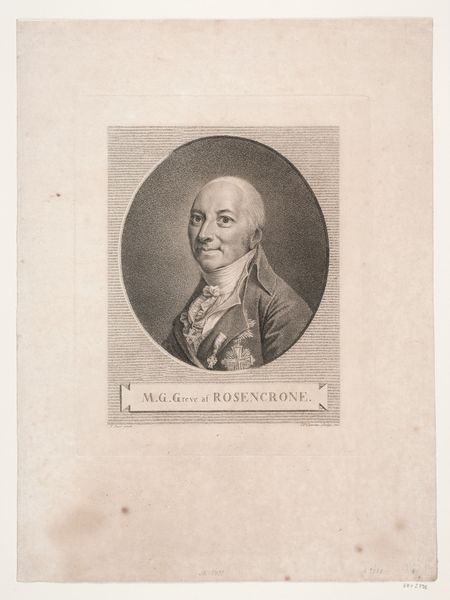

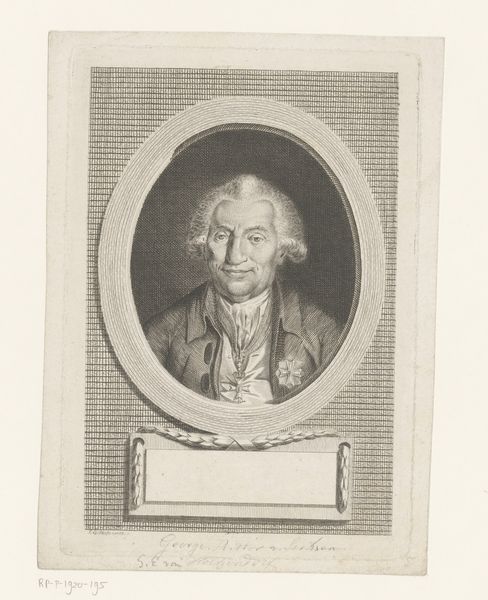

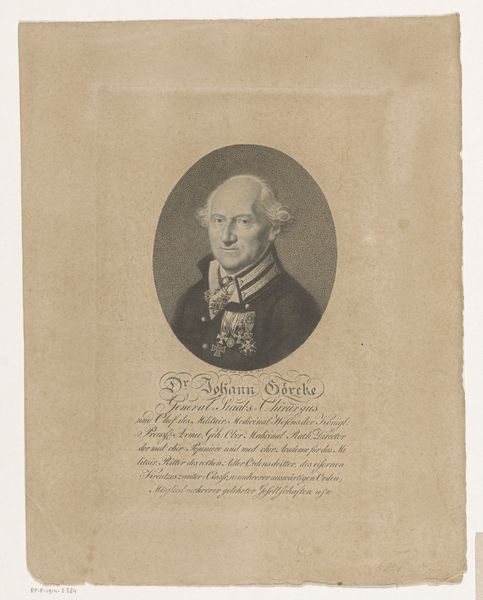

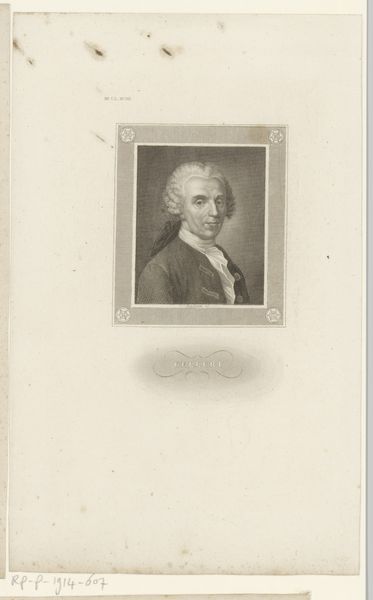

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

#

archive photography

#

historical photography

#

old-timey

#

graphite

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 316 mm, width 234 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

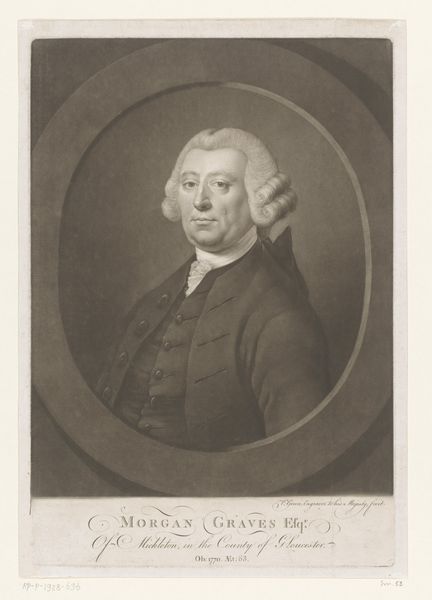

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to "Portret van een onbekende militair," a graphite and engraving piece from sometime between 1767 and 1843, attributed to Johann Carl Bock, currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: What immediately strikes me is its almost unsettling stillness. The rigid posture, the averted gaze—it all conveys a sense of restrained power, the kind that perpetuates oppressive structures. Curator: I see your point about power. Military portraits often utilize such conventions to convey authority. The man’s neatly styled hair and formal attire, for instance, visually signal his status. Moreover, that stark white powdered wig can also symbolize something deeper. It appears artificial, unnatural, as though designed to mask something that should be left unaltered. Editor: Exactly! We need to critically examine who is represented in art and why. Military figures from this period, so closely associated with colonialism and its inherent violence, necessitate scrutiny. This man, whomever he might be, actively participated in a system of exploitation, even if he remained personally anonymous. Curator: Symbolically, this artwork presents a compelling face for history. We're not talking about painting here but graphic arts: engraving. Its reliance on line work and its replicability points towards dissemination; It’s a portrait meant to circulate, meant to cement an ideal, that has a more lasting quality as historical record and can become something more universal beyond individual fame. Editor: The choice of monochromatic engraving furthers that erasure by stripping away individualization. While ostensibly documenting an individual, it reinforces the values of militarism as an apparatus of power. So the historical record becomes its tool. We need to question those symbolic choices instead of celebrating the portrait solely as an aesthetic object. Curator: Agreed, understanding those tensions embedded in art of this time helps us challenge them still resonating now. By considering that historical record for its true meaning. Editor: Precisely. Only then can we disrupt inherited hierarchies and create a truly inclusive visual narrative.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.