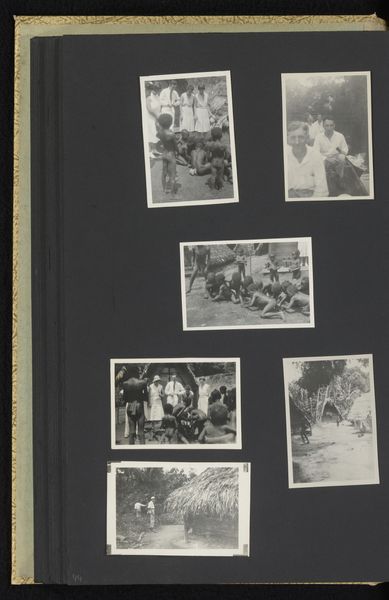

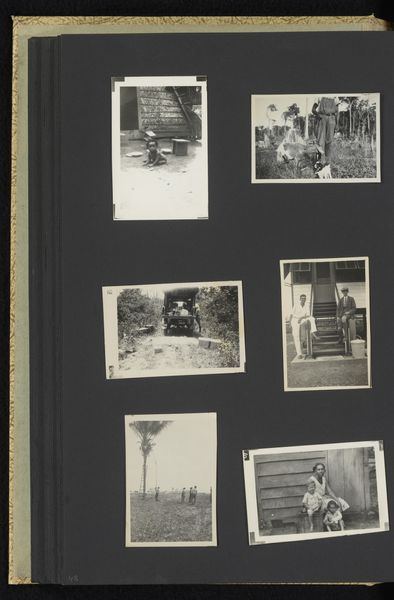

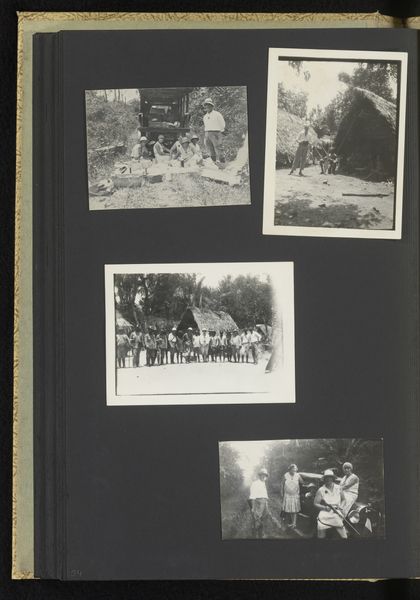

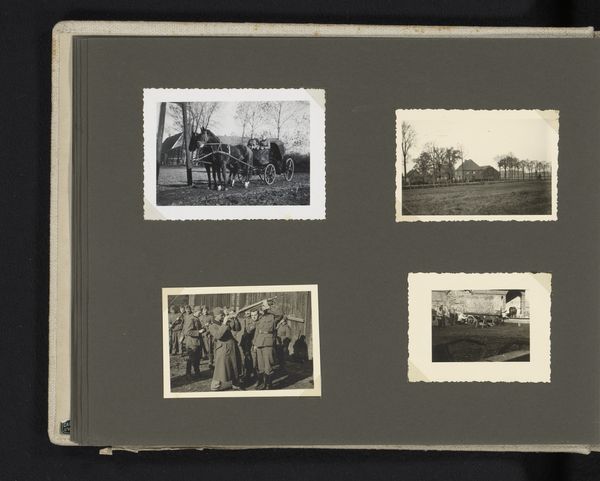

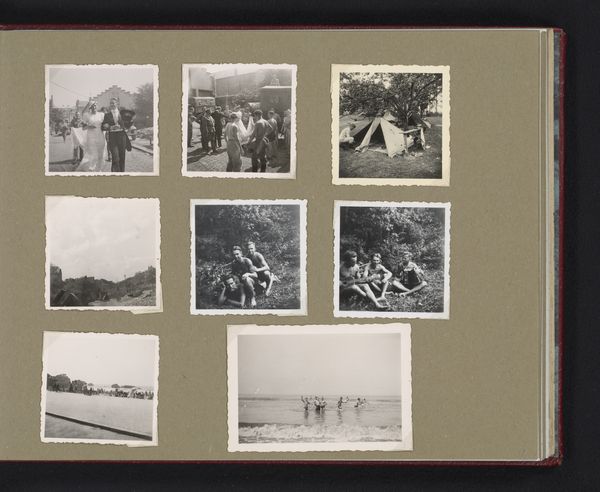

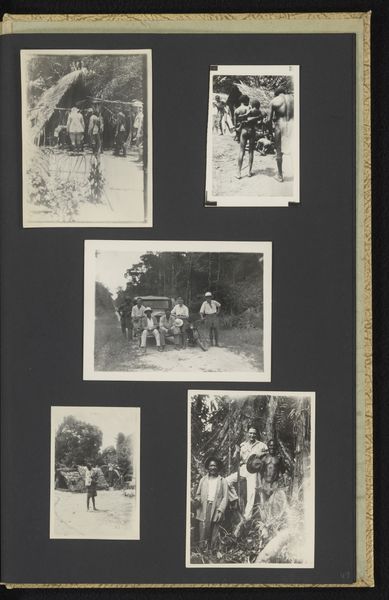

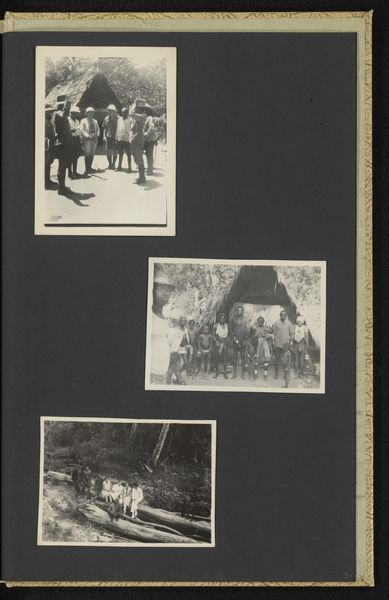

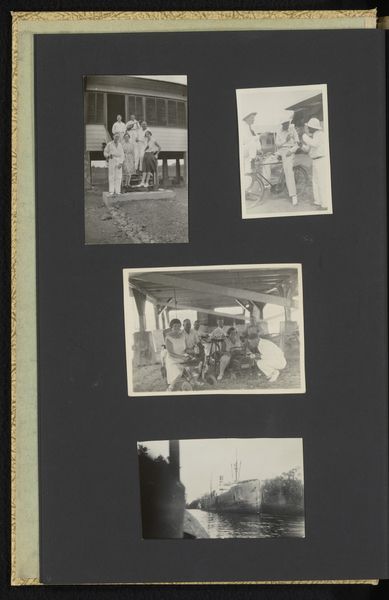

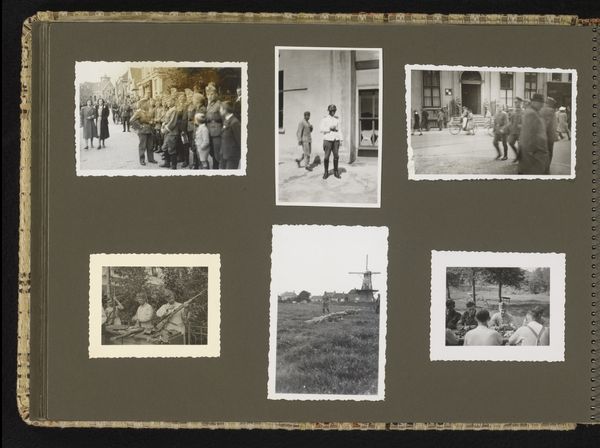

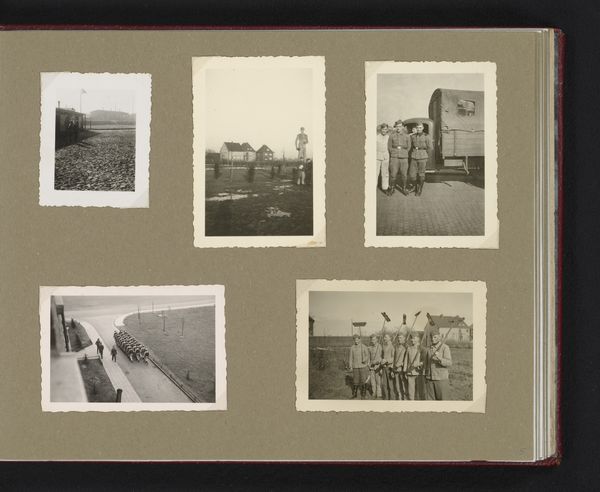

print, photography, albumen-print

#

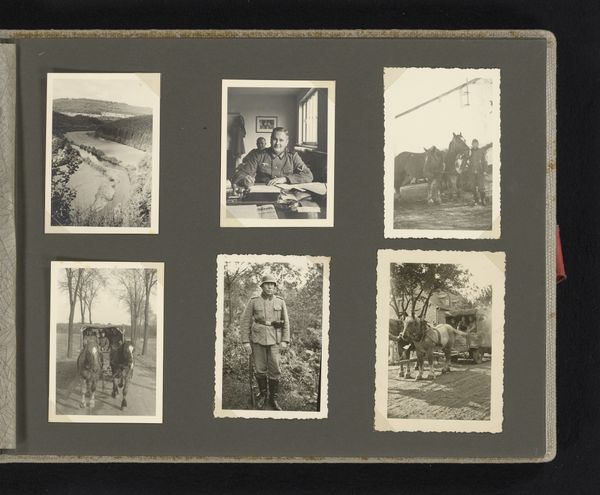

portrait

#

african-art

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 55 mm, width 80 mm, height 350 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: These evocative images before us come from a photographic album created between 1927 and 1931, titled "Bezoek aan een dorp en zwempartij"—"Visit to a Village and Swimming Party." The individual photographs are albumen prints. Editor: Albumen prints... that warmth of sepia tone creates such a powerful nostalgic mood, almost masking the harsh realities often captured within these colonial-era photographs. I’m struck by the contrast of textures, from the crisp clarity of the portraits to the grainy, almost overwhelming detail of the landscapes. It makes me consider the labor of producing them: the chemicals, the glass plates, the transport of equipment to far-flung locations... Curator: Exactly. This particular image offers a glimpse into the rituals of travel and encounter that defined colonial interactions. It shows both orchestrated officialdom and what seems to be candid moments of leisure—the swimming party. Editor: Seeing these images arranged together really highlights the complex power dynamics inherent in the colonial project. You see staged scenes alongside what appear to be everyday lives, but all mediated, documented, and presented through a very specific lens. Were these images created for personal use, perhaps souvenirs? Or were they intended for wider circulation, helping to build or reinforce a certain idea of the colonies back home? Curator: It’s most likely a combination of both. Photographic albums like these served as personal records, reminding the owner of their experiences and reinforcing their position in a hierarchical social structure. Simultaneously, such images played a role in shaping public opinion, furthering colonial agendas, and perpetuating existing narratives of empire and progress. Look at the composition choices, framing, and how light and shadow fall, for instance. It clearly indicates an exercise of control. Editor: And the stark contrast between those who appear to be colonizers and the colonized. Their labor, their bodies, everything on display… the albumen print process adds an interesting layer. The subtle shifts in tone depending on the development… was it ever employed to suggest or manipulate the “whiteness” of the colonizers? Curator: A very pertinent question. Photographic processes were absolutely tools of visual propaganda. Understanding the process by which these images were crafted helps us grasp their intentionality and underlying power dynamics. Editor: Absolutely. Viewing them collectively, as an object, drives that point home further, exposing the complex machinery behind crafting a curated reality. It leaves you contemplating photography’s complicity within colonial documentation. Curator: It indeed makes me more acutely aware of photography’s historical role in shaping colonial narratives and, importantly, our responsibility in unpacking the embedded socio-political message.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.