print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 224 mm, width 310 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

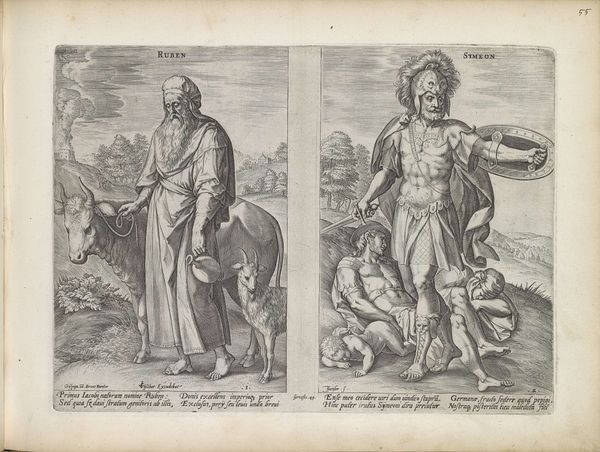

Curator: We're looking at "Stamvaders Dan en Gad," a print made sometime between 1585 and 1643 by Johann Sadeler I. It's an engraving, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. My immediate thought is it's another piece from the Northern Renaissance preoccupied with idealized masculinity and historical lineage. Editor: Lineage… right. Well, the first thing I notice is how differently "Dan" and "Gad" are portrayed. Dan is almost gentle, wielding a staff, with this sort of tragic-looking centaur behind him. Gad's all sharp angles and muscles, stepping dramatically onto armor with his big sword. One sensitive; the other brute force. It feels bifurcated. Curator: That's interesting, this bifurcated idea. Consider that these figures aren't just portraits, they represent tribes, specifically biblical figures linked to the Tribes of Israel. Sadeler is connecting these tribal founders to notions of virtue, strength, and wisdom relevant to his contemporary European audience. There's a political layer here. Who is claiming historical rights? What roles should they play in society? Editor: Ah, so the centaur and discarded armor become less random window dressing, and more signifiers! One’s legacy is tied to taming… raw wildness? Whereas Gad has left the battle behind him – proof of his dominion, the spoils of war abandoned on the field as he steps away to govern, so to speak? And, in both cases, what is lost in victory is being displayed. Is it glory? Bragging rights? Regret? Maybe a warning, that all power extracts a toll? Curator: Exactly. It also fits into a broader tradition. The late 16th and early 17th centuries in the Netherlands were periods of intense nation-building and self-definition, prints like these helped define their cultural heritage. We see the idealized masculine figures you mentioned earlier as symbols of political power and continuity. Editor: Right. It's not just aesthetics. It's visual propaganda. It's creating this feeling of... permanence and purpose. Curator: Precisely, it's about visually solidifying historical narratives for contemporary viewers. What remains are images representing a complex moment of forging both self and society. Editor: Which only underscores just how layered it all really is, isn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.