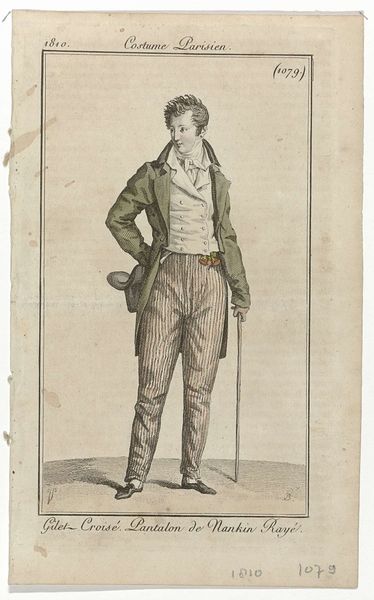

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 5 avril 1810, (1050): Pantalon de drap (...) 1810

0:00

0:00

pierrecharlesbaquoy

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

sketch book

#

traditional media

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

cartoon carciture

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

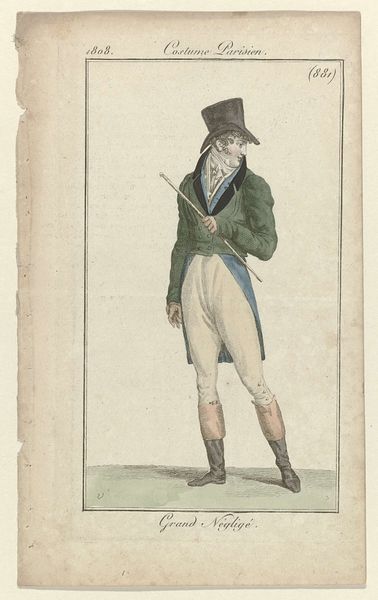

Curator: This print, housed here at the Rijksmuseum, is titled "Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 5 avril 1810." It's an engraving by Pierre Charles Baquoy, dating, of course, to 1810. Editor: It has such an elegant austerity, doesn’t it? A single figure, defined by a certain linear precision. It feels almost like an architectural drawing, spare yet poised. Curator: I find it compelling to consider these fashion plates in their historical context. Published during the Napoleonic era, it’s a moment of intense social and political upheaval. We see a shift away from the opulent excesses of the aristocracy towards a more…restrained elegance, shall we say. Editor: Yes, one almost designed for efficient movement—those fitted riding pants, for example, seem like a pragmatic reimagining of power through dress. The materials signal a rising bourgeois class that needed attire suited to their evolving societal role. It's almost proto-industrial in its sensibility. Curator: Precisely! The availability and production of "drap gris de fer," or iron-gray cloth, speaks volumes about the material culture of the time. Think about the looms, the dye processes, and the labor involved in creating even a single pair of these pantaloons. Fashion was becoming increasingly industrialized, reaching a broader market, even if the tailoring itself retained an element of bespoke craft. Editor: And gender! Consider how these garments, though seemingly conservative to our eyes, were shaping and performing gendered identity. The figure exudes an active, almost performative masculinity with those fitted pants, his carefully posed gesture... He’s dictating the scene and establishing himself as a subject in a way that both mirrored and reinforced societal power dynamics. Curator: It’s all very consciously constructed. We should also observe that fashion plates such as this also functioned as a type of proto-advertising, fueling consumption and shaping aspirations through material culture. The image becomes not just a record of style but also an active participant in constructing demand. Editor: That's right—it’s an instruction manual for a performance of status. Seeing it as a constructed document, not simply a mirror to its time, is really insightful. Thank you! Curator: A pleasure. Thinking about the materiality of fashion really grounds the era, doesn’t it? A reminder of production, labor, and societal impact behind the aesthetic facade.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.