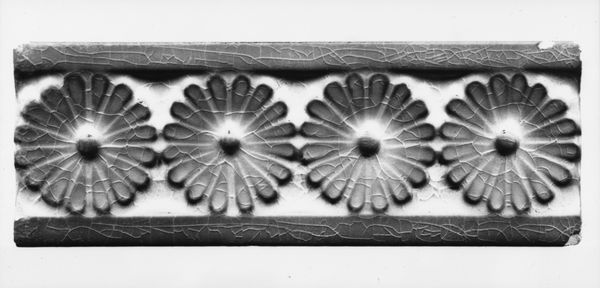

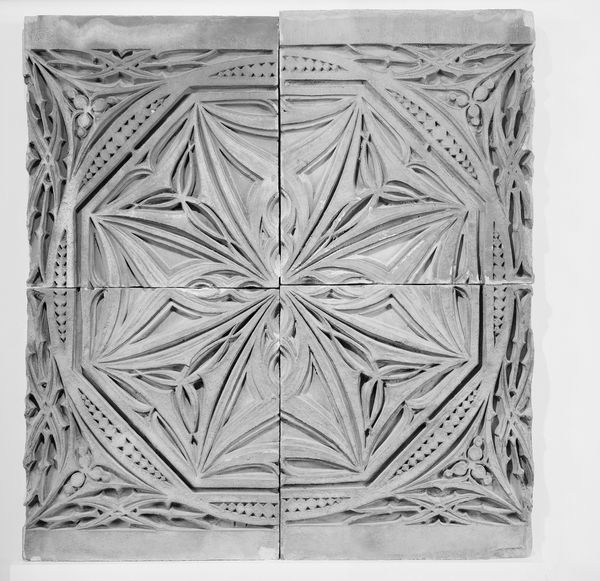

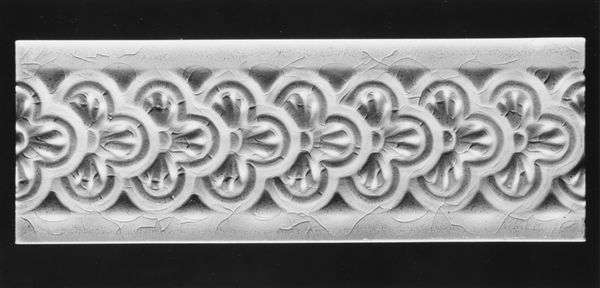

Frieze Section for the Rothschild Building, Chicago, Illinois 1881

0:00

0:00

relief, wood, architecture

#

organic

#

art-nouveau

#

decorative element

#

relief

#

organic pattern

#

wood

#

architecture

Dimensions: 17 3/4 × 37 in.

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: At first glance, the repeated patterns almost feel cold, despite the clearly organic motifs. What’s your take? Editor: This is "Frieze Section for the Rothschild Building, Chicago, Illinois" by Adler & Sullivan, Architects, dating from 1881. It's a wood relief currently housed here at the Art Institute of Chicago. I wouldn’t say cold; I see a certain deliberate austerity. Its visual impact is deeply rooted in the societal ideals of the time, especially relating to architectural displays of wealth and taste in rapidly industrializing Chicago. Curator: Absolutely. It’s an incredible example of how architectural details embody broader cultural narratives, particularly in the Gilded Age, don't you think? There’s something inherently political in these choices to decorate the spaces of commerce and power. It’s more than mere decoration; it's a visual articulation of status, deeply entwined with identity, particularly masculinity and financial power at the time. Editor: Right. And think about the institutional support for this aesthetic. This type of ornamentation wasn’t created in a vacuum. Museums, architectural societies, and even publications helped standardize and legitimize certain visual languages. The politics are embedded within those institutions and their hierarchies. What’s really striking is its embrace of the natural world via art-nouveau forms while serving a decidedly urban and commercial purpose. Curator: Exactly! The way the organic motifs are abstracted and stylized is fascinating. It reflects an urge to tame nature but also, potentially, to subtly naturalize the booming capitalist structures by embedding nature in the architecture. It also challenges the idea of absolute separation between art and utility. Editor: I agree. Considering Adler and Sullivan’s position within Chicago’s architectural scene, and the rise of skyscrapers, this piece also represents a transitional moment in American architecture—one that looks to nature but embraces new building forms. The question remains to what extent they succeeded in using organic ornament to soften or even critique capitalist building. Curator: I see your point. Regardless, engaging with the intersectional layers of history, economics, and gender allows us to unlock its potent sociopolitical symbolism, regardless of authorial intention. Editor: Yes, definitely an instance of how exploring historical contexts helps reveal the layered meanings in architectural art, allowing for a better understanding of its role within society and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.