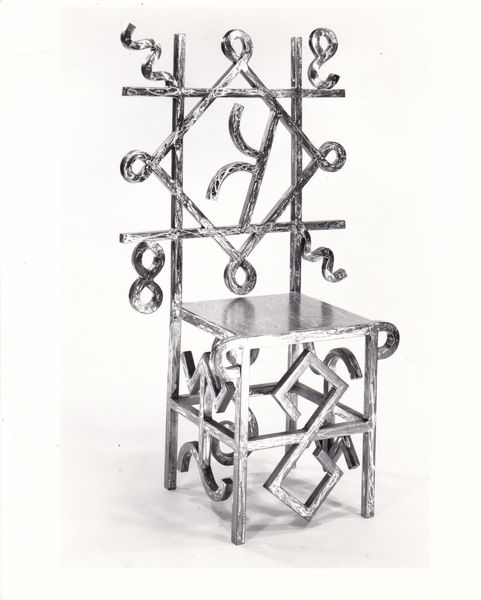

metal, sculpture

#

art-deco

#

metal

#

stone

#

sculpture

#

form

#

geometric

#

sculpture

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: 33 3/16 x 18 5/8 x 15/16 in. (84.3 x 47.31 x 2.38 cm)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

Curator: Here we have Samuel Yellin's Screen, dating from around 1930. It’s a wrought iron sculpture, currently held here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: Right away, I see a stoic guardian—very still, watchful. It feels weighty, grounded… almost like a minimalist fortress or some portal perhaps. Curator: "Portal," that's interesting. The Art Deco style here does lend it a kind of otherworldly glamour. Think of those streamlined geometric shapes combined with decorative flourishes. It suggests both industry and opulence. Editor: Well, and thinking about the material—wrought iron—there’s that duality. This is metal, forged and shaped by human hands… lots of physical labor involved, surely. Was it intended for purely aesthetic purposes, or to fulfill a functional purpose as well? Curator: It was Yellin's intent to showcase metalwork as a high art form; that’s an excellent question. His shop was renowned for its craftsmanship. Consider the societal context: decorative ironwork had been tied to craft guilds, and the Arts and Crafts Movement had also made great inroads into the realm of design. But it was also, perhaps, viewed as less significant compared to painting and traditional sculpture. Editor: So, by bringing exceptional artisanship to, what, a "screen," he’s sort of pushing the medium to declare its artistic value? The iron itself even feels elevated here. Not just a barrier, but a declaration. I keep coming back to that feeling of weight, the way it interacts with light and shadow... it's elemental, almost primeval, even within those clean Art Deco lines. Curator: Exactly! I like that idea of it as elemental, even primeval, within such sophisticated forms. A paradox. Editor: In retrospect, it really transcends merely functional or decorative—there’s a visual and even tactile pleasure here, and this speaks volumes of not just Art Deco but also of the deeply physical nature of making. It also raises questions about hierarchies—between design, art, labor, and luxury. Curator: So true. Now I'm not going to see this beautiful screen in quite the same light—or should I say, shadow! Editor: Precisely! What a robust interplay between conception and matter, vision and sweat, here.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Samuel Yellin's wrought iron creations adorn some of the finest American buildings built in the early 20th century. These include the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. (1920s), and locally, the home of John and Eleanor Pillsbury, "Southways", in Wayzata (completed 1919, demolished 2018). During this time, Yellin's shop in Philadelphia included a showroom, drafting room, library, and 60 forges for over 200 workers. Through his European training, Yellin possessed an understanding of historical styles and employed them for clients, but his most memorable designs are from his Arts and Crafts and later modernist work. An example of the latter is this screen from a series of prototypes he called "Sketches in Iron", which incorporates the angularity and dynamism of the Art Deco style. The zig-zag motifs, embellished with linear chiseled and punched decoration and adorned with tendrils forming open circles, are a clear demonstration of his combination of expertise and inventiveness in this traditional medium.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.