drawing, print, etching, paper

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

paper

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 87 × 59 mm (sheet, trimmed within platemark)

Copyright: Public Domain

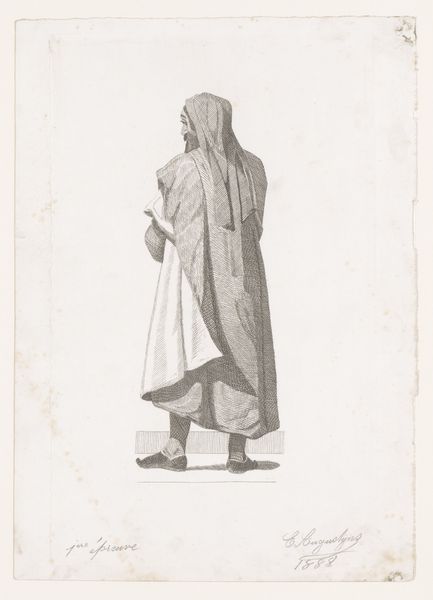

Curator: Here we have Wenceslaus Hollar’s "English Noblewoman in Winter Clothing," an etching dating from 1643. It resides here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: What strikes me immediately is the sheer amount of fabric! And the crisp lines achieved through etching – it feels tactile, almost as if I could reach out and feel the fur. Curator: Precisely. The rendering of textiles was something of a specialty for Hollar, and it offered a way to visually represent social status. The luxury of all this fabric—the fur muff, the multiple layers—speaks volumes about the sitter's place in society. We need to think of the socio-economic context, including English trade policies that shaped available resources. Editor: The lines in the dress make the eye flow from top to bottom! And think about the process – the copper plate, the acid, the physical act of marking. There is an artistry in mass production that is too often overlooked when we see these prints in museums, divorced from that context of distribution. How might it be handled? Passed around? Sold and bought? Curator: Right. These images played a role in circulating ideas about fashion and identity amongst the upper classes, reinforcing societal hierarchies through visual representation. We shouldn’t underestimate the political nature of imagery and dissemination. This noblewoman wasn't merely wearing clothes, she was performing a role. Editor: And even the paper becomes significant – its quality, its size. These factors determine cost, longevity, and how readily this image could be transported. They would give us better context for our perception of her and our roles! The fur muff and intricate layers speak to a specific climate too; imagine the labor involved in acquiring and preparing these materials, of cleaning it – what did the winter of a noblewoman entail materially and in contrast to someone else’s reality? Curator: Absolutely. So, while seemingly a simple portrait, it opens up avenues to discussing social stratification, fashion as a tool, and Hollar’s skillful engagement with the market for images during the 17th century. Editor: Indeed. I’m left pondering how art production reveals so much more than meets the eye when we think about material practices and the conditions of their manufacture and use!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.