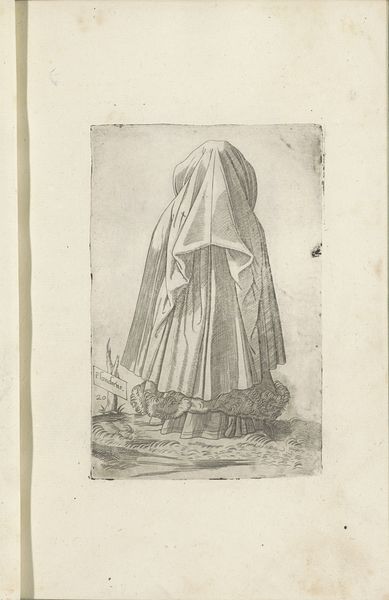

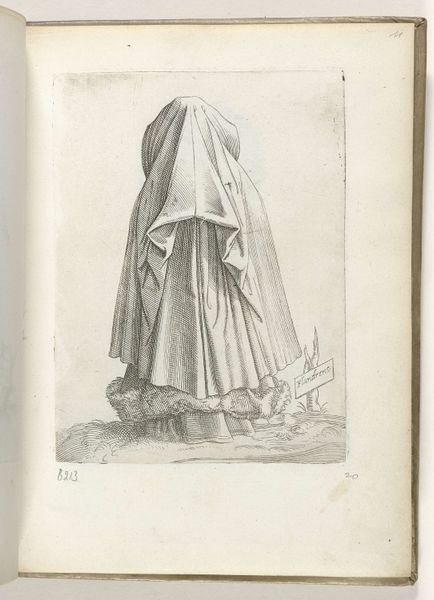

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 168 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

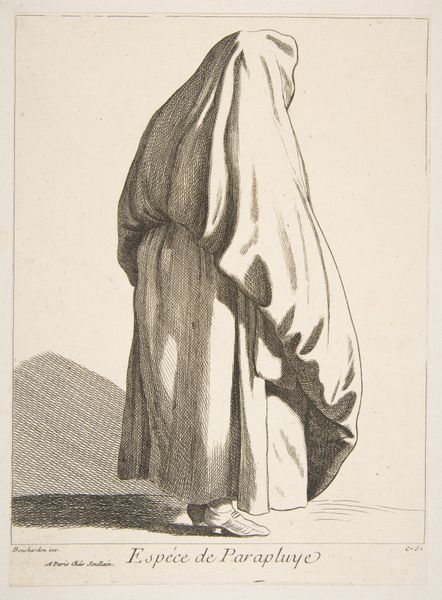

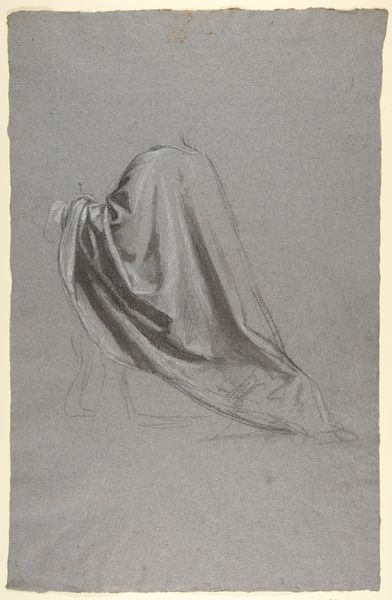

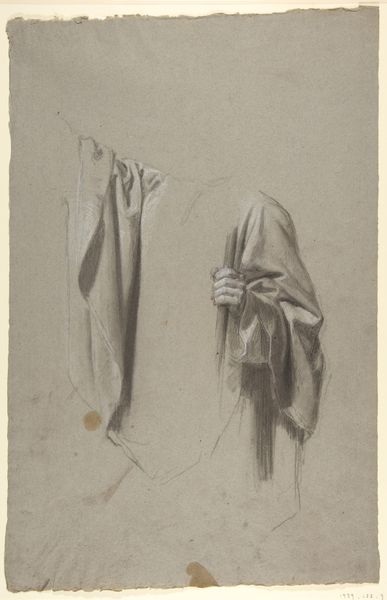

Curator: Let's turn our attention to a striking engraving by Bernard Picart from 1733, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s titled "Rouwkostuum van een Friezin"—roughly translated, "Mourning Costume of a Frisian Woman". Editor: My goodness, what a somber shroud. It looks more like a phantom than a person; that dense crosshatching, creating so much weight, I imagine it completely absorbs any light, like walking under a perpetual eclipse. Curator: Indeed. The artist meticulously employed engraving to illustrate the distinctive attire and cultural practices associated with mourning in Frisia during that period. Every etched line serves a function. Consider the implications: what does this level of detail mean for the societal emphasis on visible displays of grief and class. Editor: Yes, this isn’t some simple piece of cloth, is it? Look closely. The fall of the fabric is just right, it conveys the subject's mood beautifully. It hides the wearer but tells you everything, paradoxically. A whole culture speaks through this heavy covering. A symbol that smothers its subject. Curator: Precisely, you touch on a crucial aspect. Mourning practices in the 18th century were deeply intertwined with social status. Specific fabrics, construction methods, and the very act of commissioning a portrait or engraving broadcasted the socio-economic standing of the family in mourning. This print disseminates an image of Frisian cultural distinctiveness, transforming private grief into public spectacle through mass production. Editor: So, the materiality itself, this specific rendering in ink on paper, becomes a means of both preserving memory and staging a sort of controlled performance, eh? Thinking about the hands involved, the etcher painstakingly at his plates; the printers pulling impressions…the slow dissemination of the work, hand-to-hand. Curator: Exactly. Picart's work wasn't merely representational, it was productive of culture. The engraving itself acted as a tool—shaping understandings and expectations surrounding grief within the region, influencing local industries and crafting social identities tied to material practices. Editor: Thinking about it... such an image might be slightly dangerous! Exposing private vulnerability in the process. Anyway, It’s so affecting; such a potent, if bleak, statement about grief, culture, and selfhood all wrapped up in those inky folds. Curator: A sober image of a very distinct time, and what it means to portray the weight of mourning in eighteenth century Frisia.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.