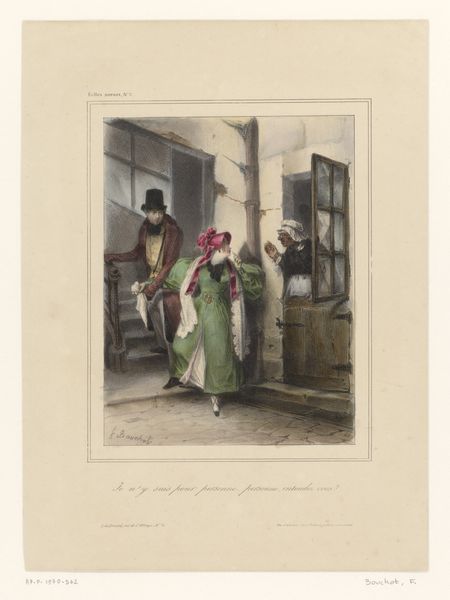

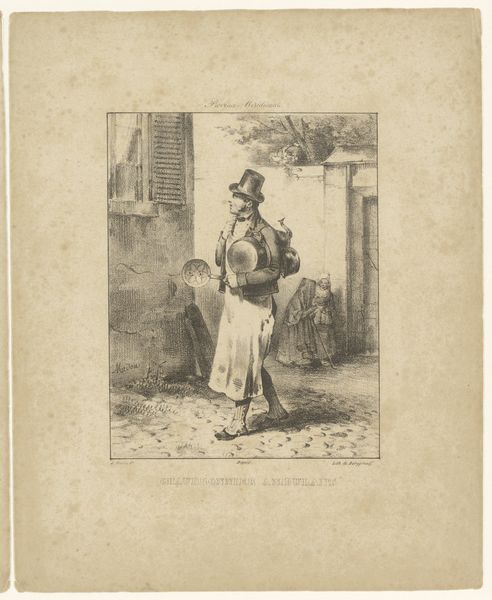

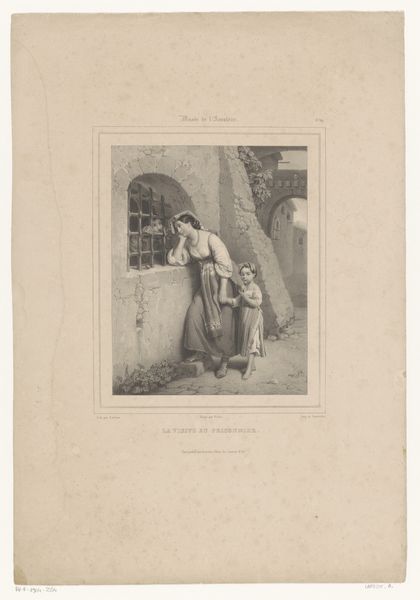

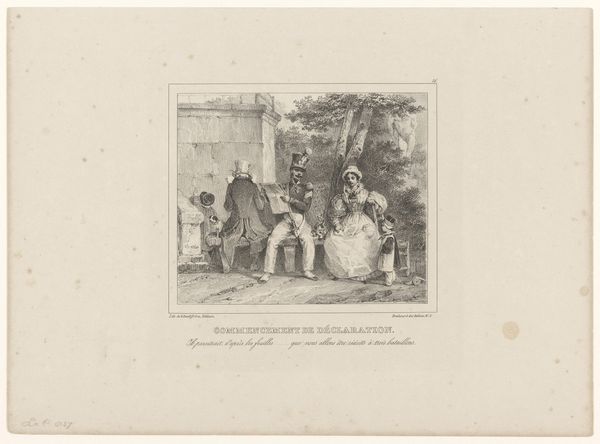

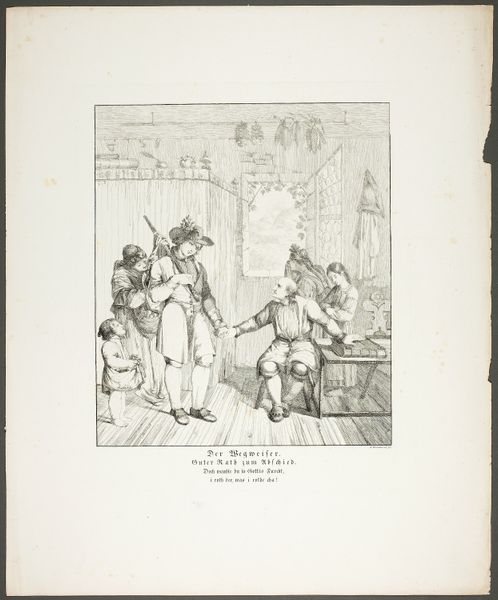

Waarzegster geeft consult aan man aan de hand van kaarten 1825 - 1829

0:00

0:00

augusteraffet

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 362 mm, width 268 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

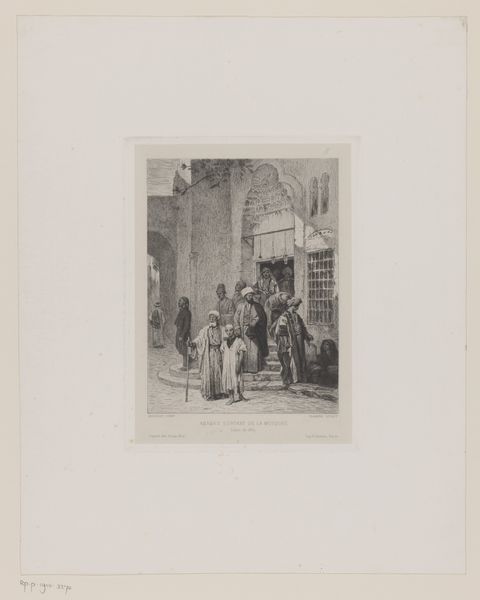

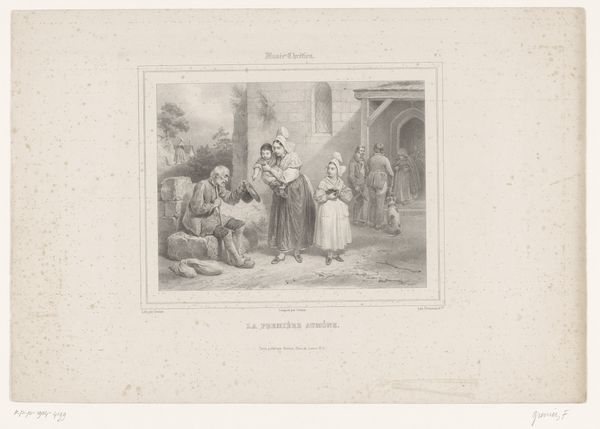

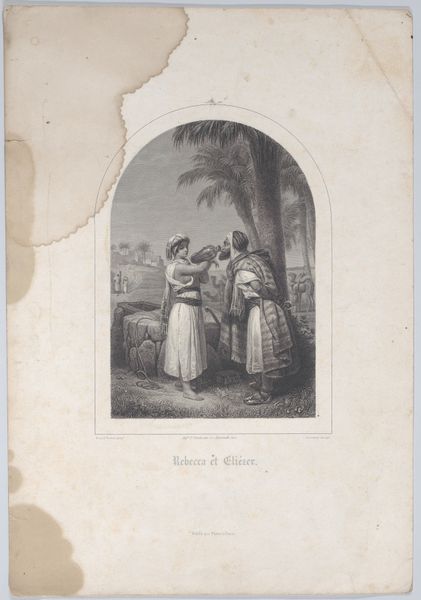

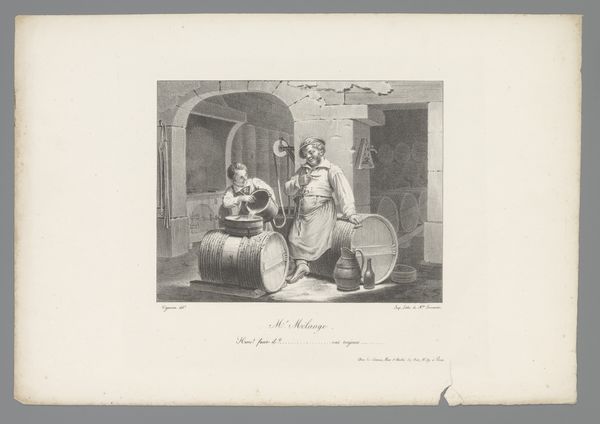

Curator: This is Auguste Raffet’s etching, "A Fortune Teller Giving a Consultation to a Man Using Cards," dating from about 1825 to 1829. The print on paper depicts a genre scene with detailed figuration. Editor: It’s a somber affair, isn’t it? The monochrome palette certainly sets a pensive tone, with such incredible detail in each etched line giving a sort of weight to the composition. Curator: Indeed. Raffet masterfully utilizes etching to create tonal variety. Notice the contrast between the stark white uniform of the man, perhaps a soldier given his attire, against the dense shading in the fortune teller's dress, indicating fabric and form. The printmaking process allowed for multiples, hinting at wider access. Editor: Yes, but look closer. Is this merely a charming genre scene, or does it offer social critique? The soldier's posture speaks of vulnerability as he hands over money, potentially highlighting the exploitation of vulnerable individuals during a time when many faced social inequality. There is certainly gender inequity visible as well in how both are depicted. Curator: I see your point. We need to consider Romanticism’s focus on the individual experience and the anxieties of the era, in tandem with printmaking’s evolution during industrialization. The fortune teller becomes both a source of hope and, potentially, exploitation, within this material framework. Editor: This consultation becomes symbolic of a larger power imbalance, I think. Who benefits from the soldier’s hope? Are the tools of divination being mobilized as a way to control individual aspirations within a structured societal system? We must ask whose interests this narrative serves. Curator: A keen interpretation. By considering these nuances – the material conditions of production, and social implications embedded in the image – we see the limitations of the supposed separation between 'high art' and what some may view as lower status imagery such as narrative etching, because here both comment upon and interact with cultural anxieties around class, social mobility, and expectation in that era. Editor: And, critically, reminding ourselves that even then, such divisions only existed for certain parties—divisions are never ‘neutral’ as it were, so it's crucial we see how race, gender and other identity intersections might shift perspectives when evaluating the narrative Raffet constructs through etching. Curator: A complex layering that challenges a singular reading, I think. Editor: Precisely; it shows the ever-lasting echoes from a very vibrant conversation—thank you for highlighting Raffet’s intriguing piece, its creation and context both inform our comprehension significantly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.