Dimensions: image: 5.2 x 8 cm (2 1/16 x 3 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

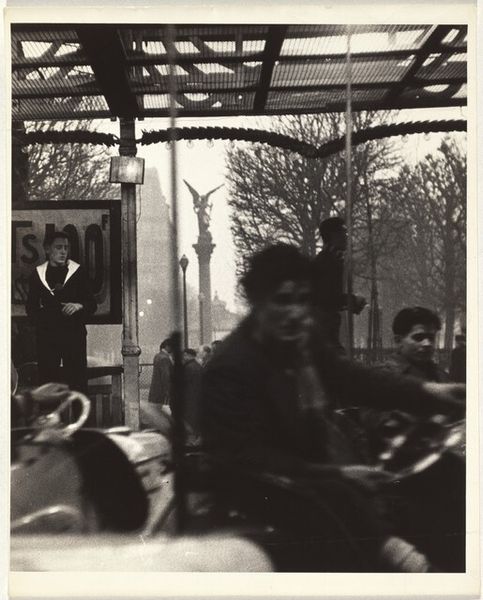

Curator: Robert Frank's gelatin silver print, "Balloons, France," dating to 1950, strikes me with its peculiar balance of joy and solemnity. Editor: My immediate impression is one of lightness despite the monochrome. Balloons against a grey, indistinct background suggest celebration, yet the absence of color leaches away some of that initial buoyancy. Curator: Frank was known for his ability to capture everyday moments, often subtly critiquing social conditions. Balloons themselves can be interpreted as ephemeral pleasures, fleeting joys within a perhaps more sober reality. Think about the rubber production of the time, likely involving exploited labor far removed from this street scene. Editor: Balloons do carry that symbolism of fleeting happiness. Throughout history, from vanitas paintings to contemporary art, they are often associated with life's impermanence and innocence lost. Perhaps here, hovering above a figure almost obscured by them, we are invited to reflect on obscured childhood memories, or joys we can no longer grasp. Curator: And that obscuring is key, isn’t it? The printing process allows for an image with stark contrasts, highlighting the grainy texture of the buildings and the sky while shrouding the person's face behind the cluster of balloons. The manipulation of material to direct our gaze and obscure identity hints at a world shaped by hidden forces, commercial production blurring individual stories. Editor: Indeed, the averted gaze! Consider the iconographic resonance of balloons as signifiers of children's parties, celebrations. In some cultures, giving them to children on important birthdays and anniversaries, representing both celebration of new life, and recognition of it passing by too swiftly. Frank perhaps reminds us to find joy within such cultural events, even with looming awareness of our ultimate fate. Curator: It is striking how this very common object, a photograph of something easily reproduced in a factory and blown up using what one could assume is French or German-made carbon dioxide tanks from WWII factories, evokes these very deep emotional responses, or allows the viewing of social tension on the streets. Editor: It's true, isn't it? From mere latex and air, something universal bubbles up – a collective understanding of both lightness and loss. Curator: Yes, indeed, even the simplest mass-produced objects often contain far more profound traces of human labor, hope and experience, than their light appearance may show.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.