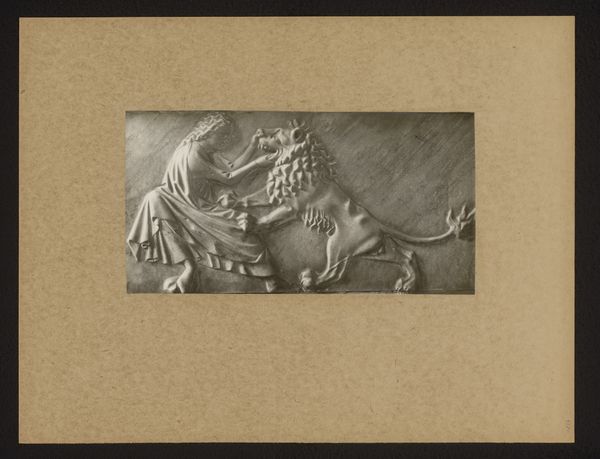

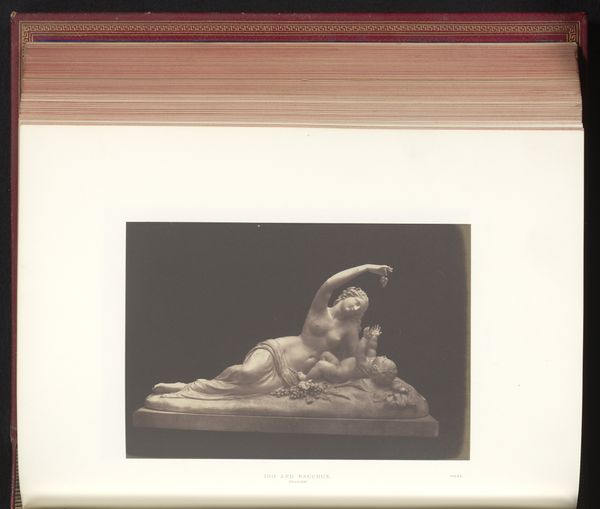

Voetstuk van een monument voor koning Frederik Willem III van Pruisen door Friedrich Drake, tentoongesteld op de Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations van 1851 in Londen 1851

0:00

0:00

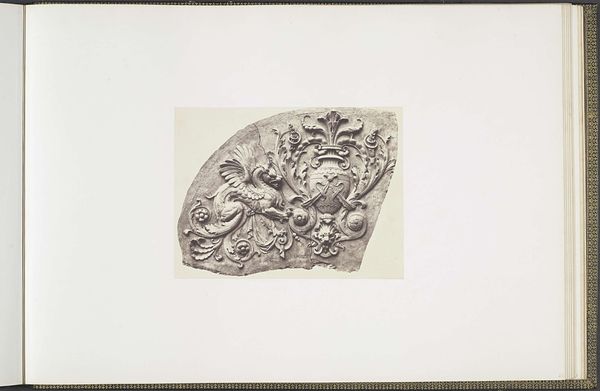

carving, photography, sculpture

#

neoclacissism

#

carving

#

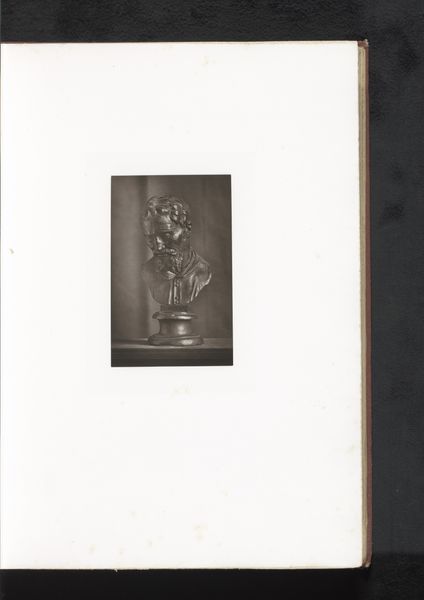

sculpture

#

figuration

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

carved

#

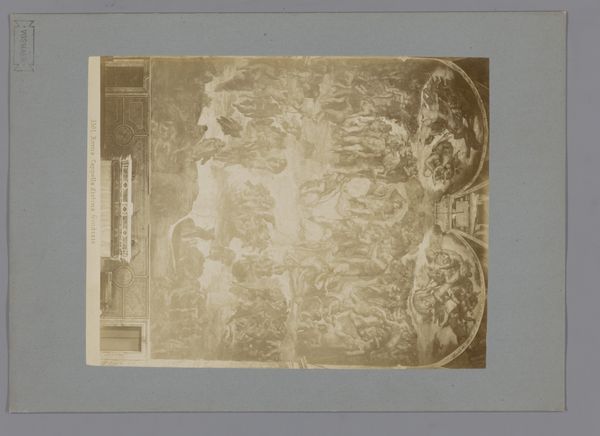

history-painting

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 177 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this photograph depicts the pedestal of a monument for King Frederick William III of Prussia, created by Friedrich Drake and displayed at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. It's… intensely neoclassical. All that marble looks incredibly heavy. What's your read on this piece? Curator: As a materialist, I find this piece interesting, precisely because of the intensive labor required. Consider the act of quarrying that much marble, transporting it, and the sheer manpower needed for carving. Think about the social context. This was a moment of immense industrial growth and capitalist expansion, so in viewing this, one can immediately question who benefits and who pays when constructing monuments that glorify figures such as King Frederick William III? Editor: I hadn't considered the labor involved beyond the artistic skill. What does its presence at the Great Exhibition say about the monument's, and therefore the Prussian king’s, perceived value? Curator: Exactly. The Great Exhibition was a celebration of industrial power, and exhibiting this sculptural element serves as both propaganda and advertisement. It shows the ability to marshal resources – raw materials, skilled labor – on a grand scale. We must think about how the monument operates as a form of social currency within the political theater of 19th century Europe. To create it, you have processes of consumption. How much marble, how many people's salaries, and, crucially, what alternative means might have put the funds allocated for its production toward other purposes? Editor: So, we're examining not just the art, but the economic and social systems it reflects and relies on? Curator: Precisely. The photograph is a document capturing a specific manifestation of power relations. The carving embodies status. Editor: This has completely changed how I view not just this sculpture, but the very nature of monuments in general. Curator: Indeed, by focusing on the materials, process, and context, we see how art and power intersect.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.