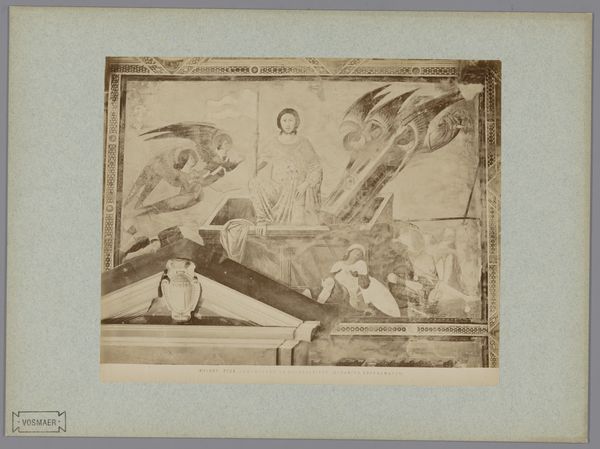

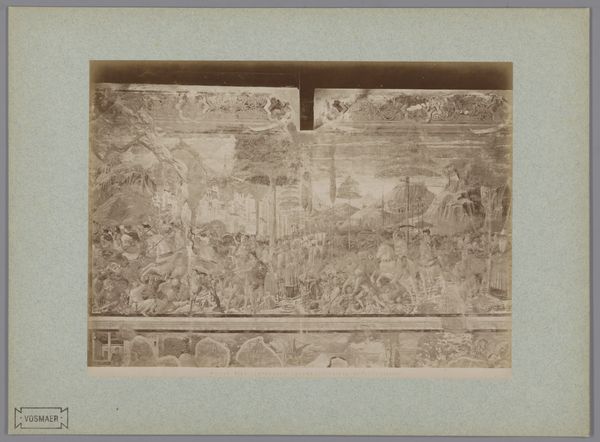

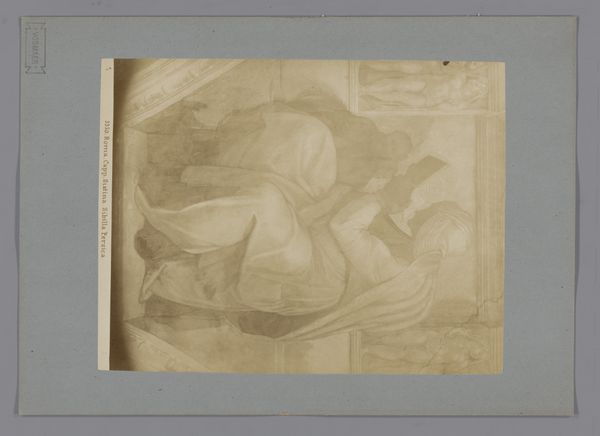

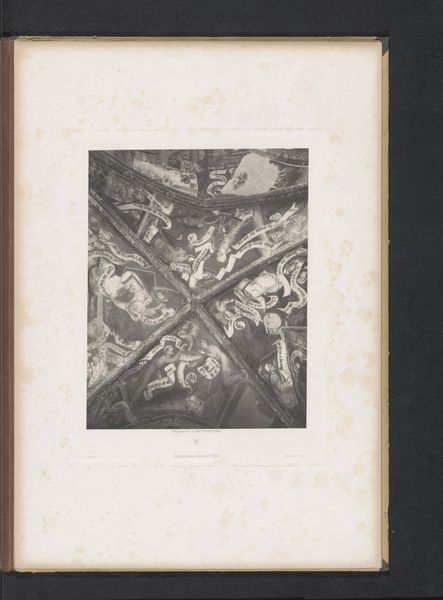

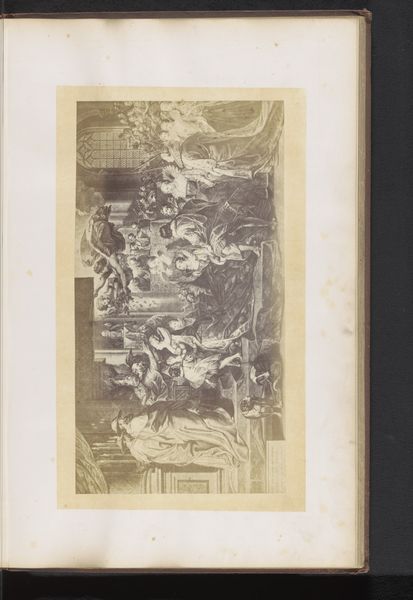

Fotoreproductie van een fresco van het Laatste Oordeel door Michelangelo in de Sixtijnse kapel 1851 - 1900

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, fresco, photography

# print

#

fresco

#

photography

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: height 256 mm, width 197 mm, height 354 mm, width 253 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at a photograph of Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” fresco, taken sometime between 1851 and 1900. It's a print made from a photograph of the original fresco found in the Sistine Chapel. Editor: Chaos, pure Renaissance chaos! My eyes don’t know where to land. Bodies swirling, a storm of limbs, it feels less like judgment and more like a heavenly mosh pit. Curator: That's a great way to describe it. Michelangelo abandoned traditional symmetrical depictions, opting for this swirling, dynamic composition. This reflects a shift in thinking about divine judgment itself. It’s far less ordered than earlier depictions. Editor: Ordered? If I was awaiting judgment, I'd prefer order. This image practically screams, "Good luck figuring out where you're going!" What symbols am I supposed to grasp here? Curator: Well, the figures are arranged hierarchically, with Christ at the center, surrounded by saints and the Virgin Mary. The ascending figures on the left are the saved, rising towards heaven, while the damned on the right are dragged down to hell. Each saint has their distinct symbol – Saint Bartholomew, for example, famously holds his own flayed skin. Editor: Okay, a roadmap of sorts for the afterlife. And that flayed skin—pleasant imagery! So much suffering etched in the stone, then captured in this photograph. It’s like a dark mirror reflecting our anxieties. Did photography change how people viewed such sacred artworks? Curator: Absolutely. Before photography, most people only knew this work through descriptions or less-than-accurate reproductions. Photography provided much wider access. However, this particular photographic print carries its own cultural weight as a late 19th-century interpretation and documentation method, imbuing the fresco with a fresh perspective. It allows for both preservation and democratization of a cultural icon. Editor: Hmmm, fascinating! To capture something so timeless with the latest technology, this late 19th-century camera, it is quite intriguing. A copy of a copy. Ultimately, though, I just can't shake that feeling of…overwhelm. Curator: Indeed. It mirrors, in some ways, the complex and often overwhelming nature of belief itself. Editor: Yes, Michelangelo certainly aimed for that level of profound existential vertigo! Well said!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.