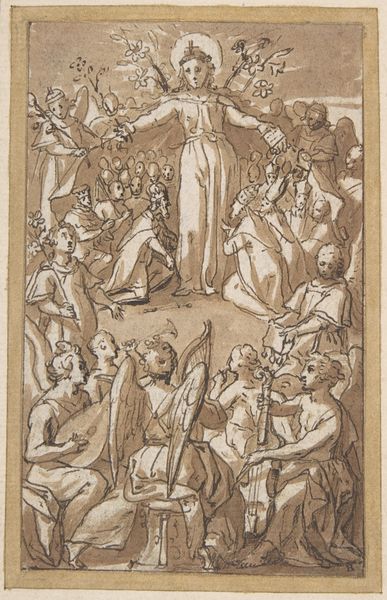

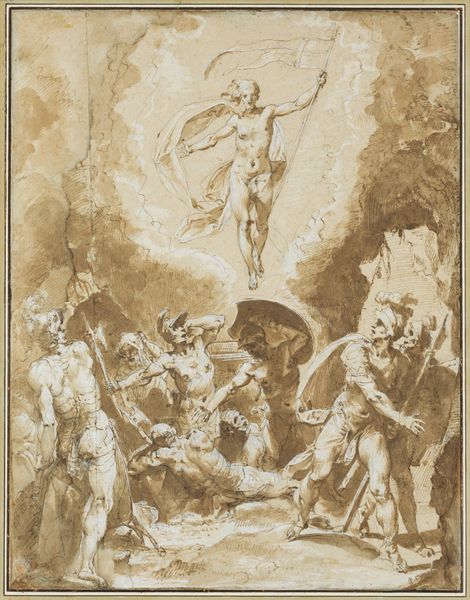

Saint Benedict Orders the Destruction of Idols at Montecassino 1694 - 1759

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

ink painting

# print

#

figuration

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

angel

Dimensions: 8 7/16 x 4 3/4in. (21.4 x 12cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Gaspare Serenario's drawing, "Saint Benedict Orders the Destruction of Idols at Montecassino," likely created sometime between 1694 and 1759. It’s a striking ink drawing, currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It’s intense. A flurry of destruction, dominated by earth tones, conveying both violence and... piety? Is that a sword-wielding angel floating overhead? Curator: Yes, the angel with a sword definitely adds to the drama. But consider the composition as a whole. Serenario skillfully employs symbols of the triumph of Christianity. Note how St. Benedict stands serenely in the center, a beacon of order amid the chaos, while his followers dismantle pagan idols. It speaks volumes about power dynamics in the era. Editor: You are right. Benedict does dominate the frame, yet the destructive act feels ambivalent. The angel feels like a divine warrant for the iconoclasm unfolding below. But at the same time, the shattered idols at the feet of people carry stories, culture. Was all that destroyed so easily and completely? Curator: It wasn’t that simple, of course. Historical context is crucial here. This scene represents a pivotal moment in the establishment of the Benedictine order and the broader conversion of Europe. The physical act of destroying idols served as a powerful symbol of spiritual cleansing and societal transformation. We have a similar tradition reflected across culture and eras, really, of symbolically casting off the prior to step into the new, but not always through destruction like this... Editor: It does raise difficult questions about the suppression of belief. You make a good point that there are cultural commonalities in casting out the prior, so there’s a very charged symbolism at play here, even beyond the explicitly Christian content. Curator: Exactly. And beyond its historical and religious significance, I find the artwork technically impressive. Serenario masterfully uses ink to create depth and movement. The dynamic poses of the figures, the interplay of light and shadow… it all adds to the emotional intensity of the scene. Editor: It leaves me contemplating the complicated relationship between faith, power, and cultural memory, I appreciate this. Thanks for pointing out the artful and emotive detail amid such turmoil!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.