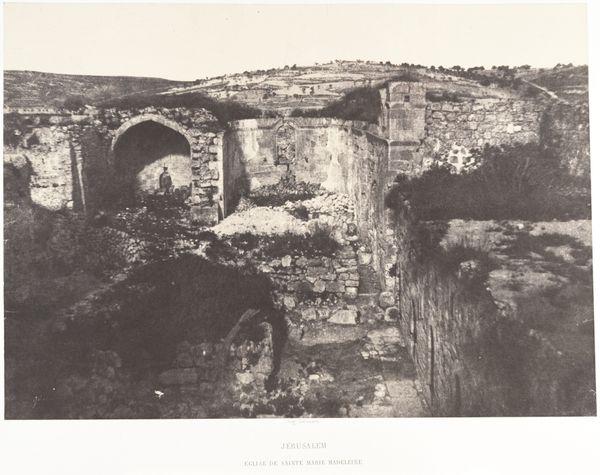

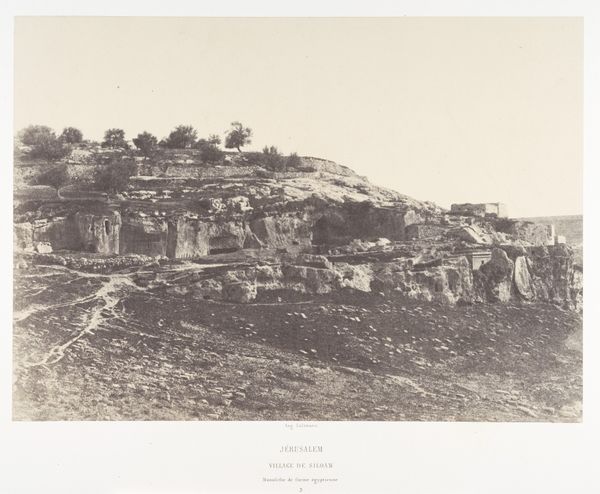

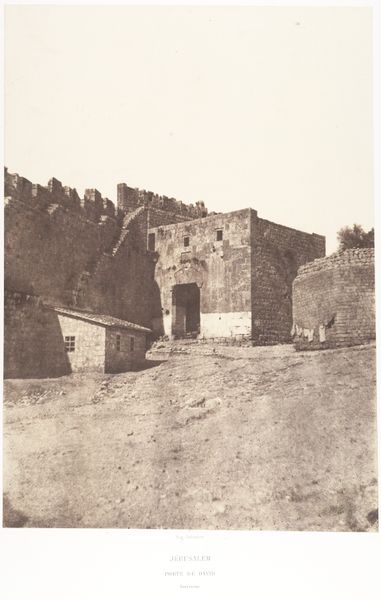

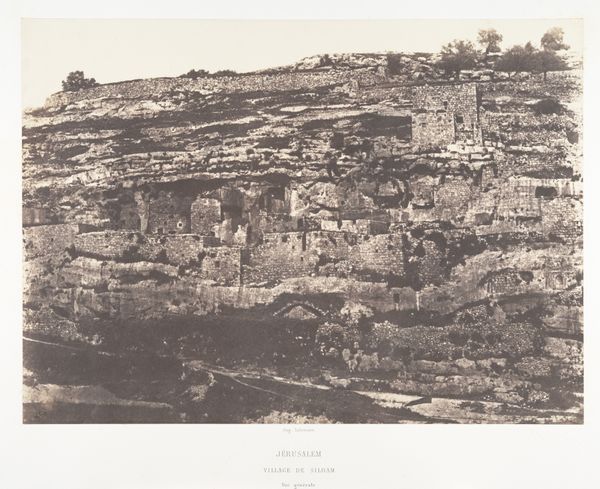

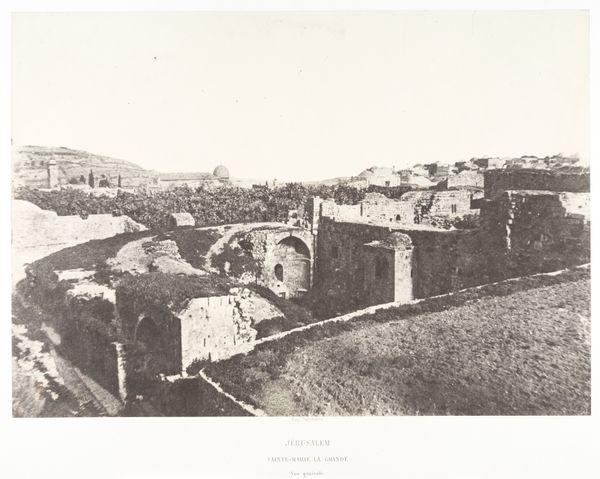

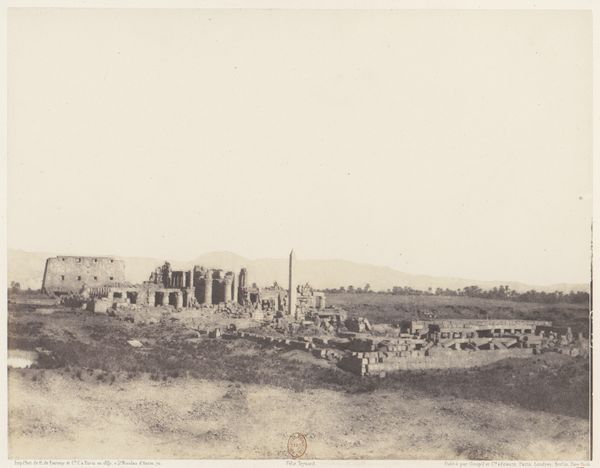

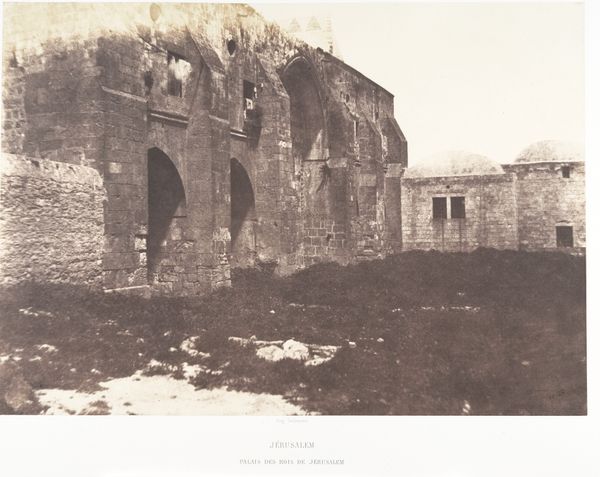

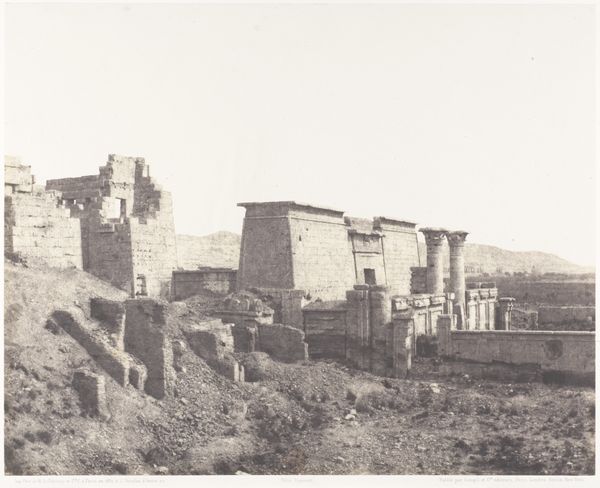

photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

architecture

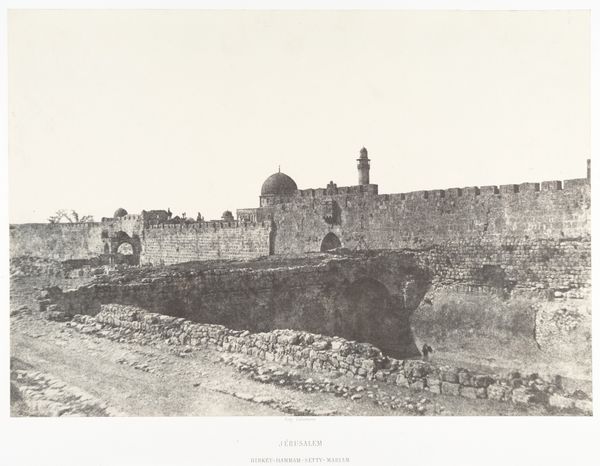

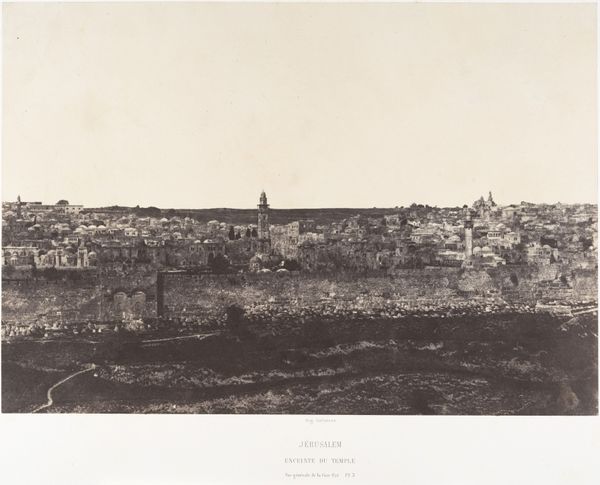

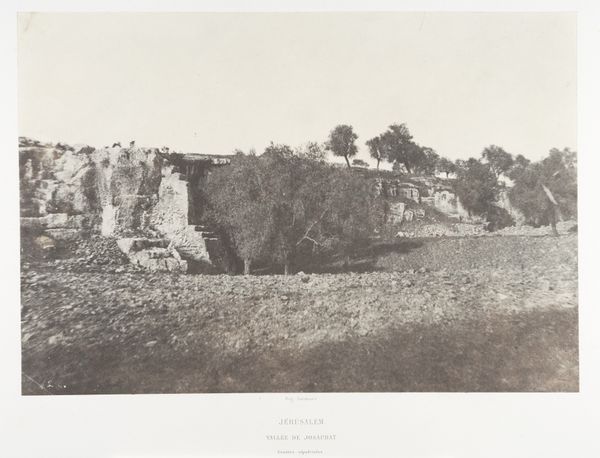

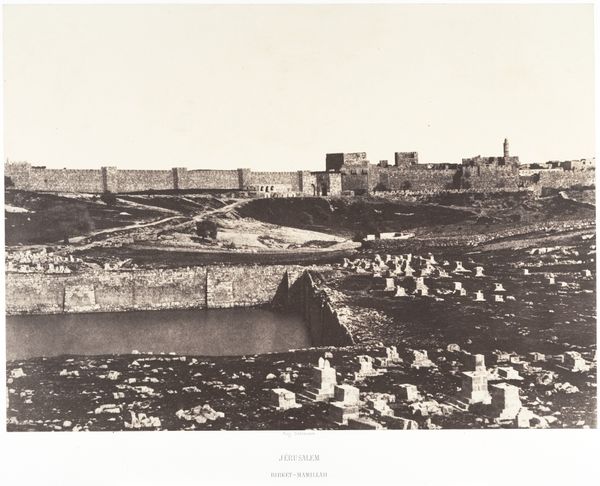

Dimensions: Image: 22.6 x 32.2 cm (8 7/8 x 12 11/16 in.) Mount: 44.9 x 60.4 cm (17 11/16 x 23 3/4 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Auguste Salzmann's gelatin silver print, "Jérusalem, Côté Est de Jérusalem," taken between 1854 and 1859. There's a real starkness to the image, this feeling of history laid bare through the crumbling architecture and barren landscape. What's your take on it? Curator: This photograph offers more than just a picturesque view; it's a document steeped in the complexities of Orientalism and early archaeological endeavors. Salzmann, commissioned to "prove" biblical accounts through photography, inevitably projected a European perspective onto this landscape. What do you think that perspective might be highlighting or, perhaps, obscuring? Editor: Well, the clarity, the almost clinical way the ruins are captured, feels very… detached. Like an attempt at objective documentation, perhaps? Curator: Precisely. Yet, even the act of documenting is a political one. Consider who gets to represent whom and for what purpose. Salzmann's work contributed to a visual archive that, while seemingly objective, served to reinforce a colonial gaze upon the East. Do you think the absence of people contributes to this feeling? Editor: It does. The absence amplifies the sense of the land as simply a resource, open for interpretation, rather than a place with an existing, continuous history. It's very thought provoking. Curator: Indeed. The photograph also participates in the 19th-century discourse surrounding the 'authenticity' of religious sites. Salzmann aimed to capture what he saw as the original Jerusalem. His intentions reflected Europe's interest in the area through photography and archaeological investigation. Editor: It's incredible to think about the layers of meaning embedded within a single image. This makes me consider how a photograph becomes an artifact, loaded with not only historical data, but also power dynamics and perspective. Curator: Absolutely. By critically examining the historical and social context in which art is created, we come to see them as not just aesthetic objects, but as mirrors reflecting our own biases and preconceptions. Editor: I will definitely keep all that in mind in the future!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.