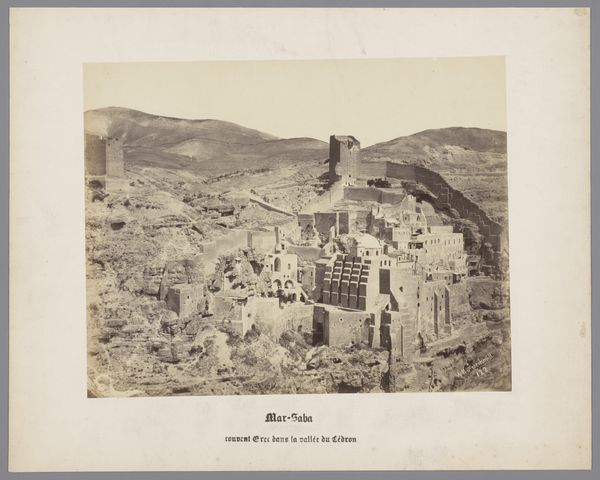

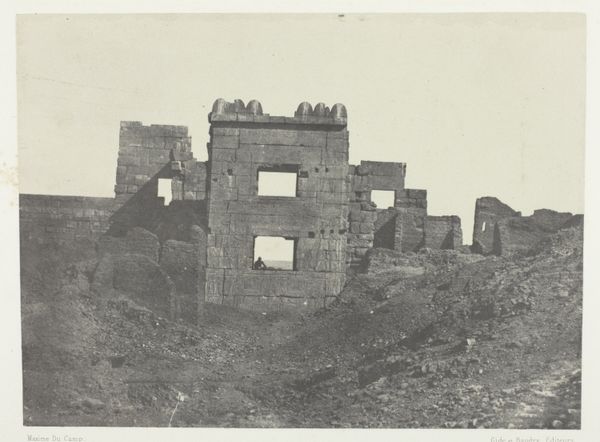

photography, site-specific, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

landscape

#

photography

#

site-specific

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

Dimensions: image: 20.3 × 26.1 cm (8 × 10 1/4 in.) sheet: 35.5 × 53.6 cm (14 × 21 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: This photograph, "Monastery of Mar Saba," a gelatin silver print taken around 1855 by James Graham, it has a very grounded feeling. The landscape and architecture seem integrated somehow. How do you interpret this work, thinking about the landscape? Curator: That grounded feeling you're picking up on speaks volumes about the context in which this photograph was made. The mid-19th century was a time of intense Western engagement with the Middle East, often framed through colonial power dynamics. Consider how photography, then a relatively new technology, was used to document and, in a way, claim ownership of these "exotic" landscapes and cultures. What might this image be saying, or not saying, about that relationship? Editor: Well, it feels different from some of the Orientalist paintings I've seen, there’s a realism here, it seems… less staged. Curator: Exactly. And that supposed "realism" is precisely what makes photography so powerful—and potentially misleading. But also, who was Graham photographing *for*? The imagined Western audience? Or was there an element of dialogue or exchange with local communities? The composition and starkness almost resists the romanticized view. It seems he had an agenda to capture how it *is*. Editor: That makes me wonder, too, about what's absent from the frame. Are there stories and perspectives left out? Who are the people connected to this architecture and site, and how would they represent it themselves? Curator: A critical question! These absences speak just as loudly as what’s present. Thinking about Islamic art history, photography also offered an objective method for preservation. It gives clues as to architectural techniques. Perhaps he wanted to show, objectively, that Mar Saba really existed, unlike Biblical stories. Editor: This makes me think differently about these older photographs. It’s more than just the image; it’s the relationship behind it. Curator: Precisely! And by engaging with that relationship, we can start to unpack some of the complex and often uncomfortable histories embedded within seemingly simple images.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.