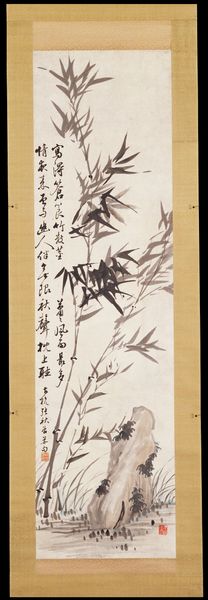

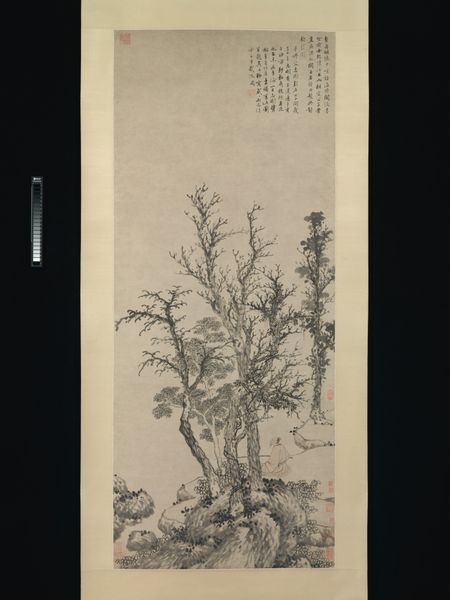

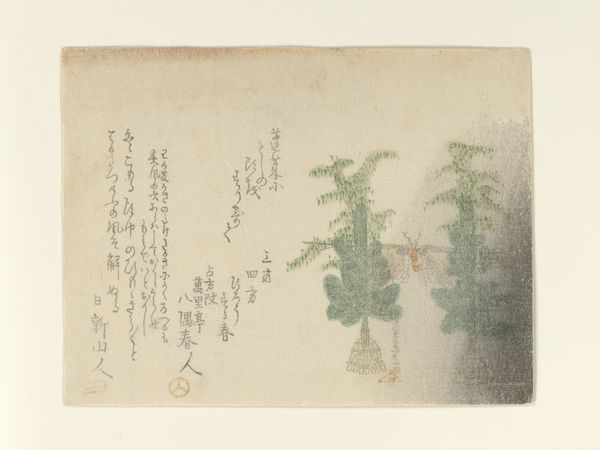

painting, paper, ink-on-paper, hanging-scroll, ink

#

aged paper

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink-on-paper

#

hanging-scroll

#

ink

#

china

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this ink-on-paper hanging scroll is entitled "The Giant Rutabaga from Fu-Yang," created around 1715 by Li Shan. The sheer scale of the rutabaga is striking; it almost feels…unreal. What's your read on this piece? Curator: The painting's significance goes beyond just portraying an oversized vegetable. In Qing Dynasty China, botanical depictions weren’t just about representing nature; they were deeply intertwined with socio-political commentary. Given Li Shan’s status as one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou, we might ask how this work challenges established artistic conventions and, perhaps, social norms. Is it simply a celebration of abundance, or could it be a subtle commentary on the extravagance or even the failures of the ruling class? Editor: So the unusual subject matter is already a bit of a statement in itself? Curator: Precisely. Think about the context: Yangzhou was a bustling commercial center, known for its wealthy merchant class. These patrons often dictated artistic trends. But here, we see Li Shan elevating a common root vegetable to monumental status. Does this choice, along with the artist's calligraphic inscriptions, elevate the commoner? Editor: I hadn't considered the social dynamics at play. I was focused on the strangeness of a giant rutabaga. Curator: It’s easy to get caught up in the literal depiction, but understanding the art world's social and institutional forces can really open up new layers of interpretation. It encourages us to look at not just *what* is painted but *why*. Editor: This is really helpful. I see that by questioning the established artistic styles it also questioned society itself. Curator: Indeed, understanding the art historical, political, and social background has allowed a seemingly simple picture of an outsized vegetable to represent a statement that questions existing norms.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Li Shan was born in Xinghua, Jiangsu province, into a prominent family of scholars and officials. He was schooled early on in painting as well as poetry and, during the Kangxi reign (1662-1723), he earned an appointment to the Imperial Study. With the death of the Kangxi emperor, Li Shan moved to Yangzhou where his declining fortune forced him to increasingly paint and produce calligraphy for a living. His talents were recognized and he was eventually categorized as one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou. While the real subject of this unusual painting of a giant rutabaga is ink play and expressive brushwork, the artist's inscription adds to the playfulness: Master Zhongting the minister requested me to paint for him a Fuyang rutabaga. It is reported that during late Han an army of Cao (d. 220 CE) numbering 830,000 descended on Jiangnan and could only eat half of one so its size cannot be exaggerated. No one knew how many thousands of feet high the bridge at Luoyang was and a man from Fuyang wished to go and look at it. Along the way, he met a man from Luoyang going to Fuyang to view the giant rutabaga. The Fuyang man related the story of the rutabaga and the Luoyang man declined to go on (concluding that it was just a tall tale). The man from Luoyang then described the height of the bridge: "During the seventh lunar month of last year a boy jumped from the bridge. It is now almost spring and he has yet to hit the water." The Fuyang man then decided not to go (to Luoyang concluding the Luoyang man was just a braggart). Recorded and painted by Li Shan

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.