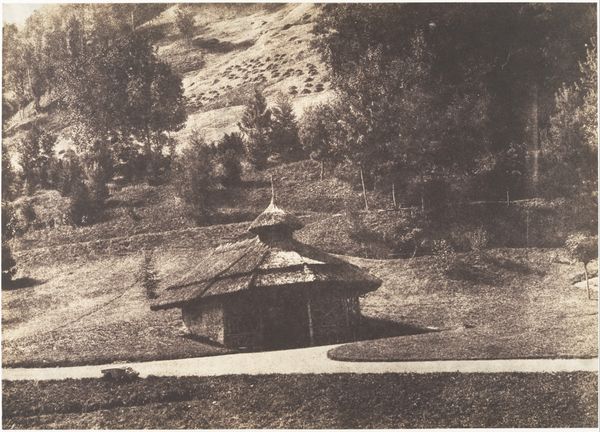

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

black and white format

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 22.4 x 16.7 cm (8 13/16 x 6 9/16 in.) mount: 34.8 x 27.6 cm (13 11/16 x 10 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

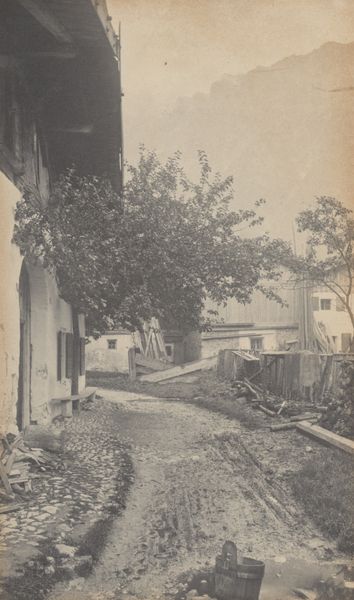

Curator: Oh, there's a palpable quietude about this photograph, isn’t there? A gentle rhythm of life. Editor: Yes, and a certain timelessness, too. This is Alfred Stieglitz’s “At the Pump, Black Forest,” a gelatin-silver print made sometime between 1894 and 1934. Curator: Black and white softens it somehow, elevating the everyday to something… poignant. Look at the way the light catches on the woman’s kerchief, it is simply marvelous! You feel this scene isn't just captured, it's almost remembered, if that makes sense. Editor: It does. Stieglitz was deeply invested in Pictorialism, the idea of imbuing photography with an artistic sensibility, making it more than just a record. He fought to have photography seen as an art equal to painting and sculpture, believing the photographer had a right, an obligation even, to manipulate the image, to impress their vision upon it. Curator: You see that manipulation in the dreamlike blur of the distant landscape. It isolates the woman, almost staging her act of gathering water. But it's not isolating in a sad way. She’s contained, centered. Safe, perhaps. Editor: Right, the Black Forest as a setting held particular resonance. It represented an ideal, an escape from the rapidly industrializing world. A return to simpler values. And Stieglitz, along with many artists of the time, felt a strong pull towards documenting and perhaps preserving this quickly disappearing way of life. Curator: She feels connected to her environment. Look how the pump almost blends into the architecture of the house! You're right; this piece speaks about yearning. Not just for simpler things, but for connection. To the land, to heritage, to oneself, you know? Editor: Precisely. He presents an idyllic vision steeped in the realities of rural labor, suggesting it could offer genuine solace amidst broader societal shifts. He suggests an enduring image. Curator: Yes, it's beautiful because it’s still. Stillness captured perfectly, suspended in time. A pause. Editor: So, as viewers, maybe we should just breathe deeply and appreciate what this stolen moment has to offer, from a distant time and place.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.