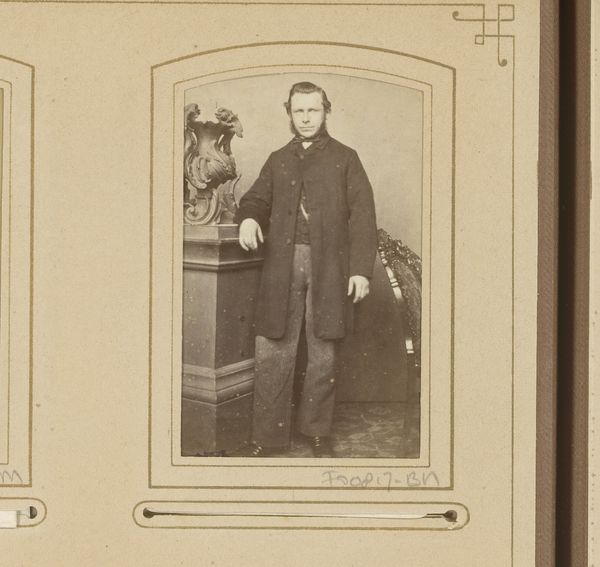

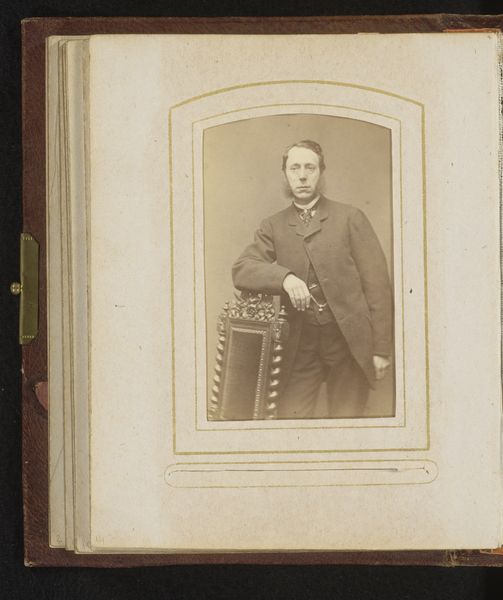

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

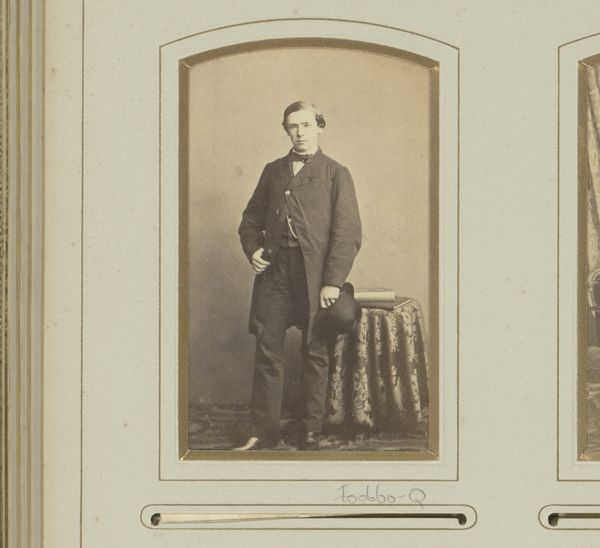

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Portret van een geestelijke met hoed in de hand," or "Portrait of a Cleric with Hat in Hand," a daguerreotype from circa 1855 to 1870, by Delehaye & Sluyts. It’s quite striking how still and composed the subject is, very much in line with portraiture of this time, but I can’t help wonder about his story. What do you see in this portrait beyond its initial appearance? Curator: I see a reflection of the socio-political climate of the 19th century. Photography, especially the daguerreotype, became a tool for constructing and reinforcing social hierarchies. Note the carefully constructed pose of the cleric: the hat held respectfully, the austere clothing, the symbolic column. Consider the power dynamics inherent in this representation. Who was being represented, and why? What were they trying to project, and more importantly, what were they trying to hide? Editor: Hide? What do you mean? Curator: The photograph flattens complexities. The cleric is positioned to present authority, respectability. But how might that perceived authority relate to gender dynamics, colonial aspirations, class inequalities during that historical moment? Doesn't this image subtly embody institutional power? And how did portraiture, particularly in its staged nature, serve to uphold those existing powers? Editor: I hadn’t considered the connection to social structures so directly. I was focused on the individual. Curator: And that’s precisely what makes it so effective. But what if we viewed the cleric, not just as an individual, but as a node within a complex web of institutional power relations? Editor: This gives me a lot to think about. Looking beyond the surface and considering those power structures makes the portrait much more dynamic. Thank you. Curator: Indeed. It's these critical lenses that make art history continually relevant.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.