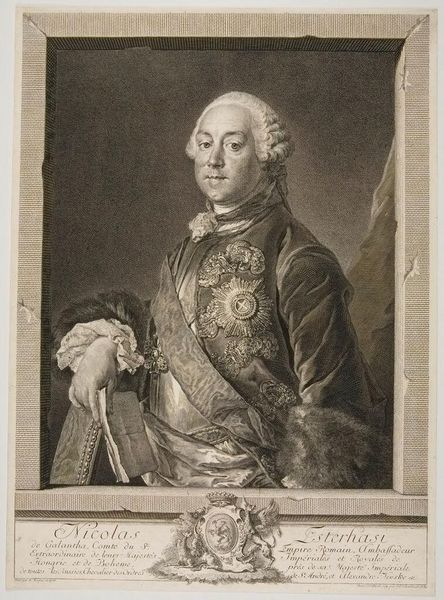

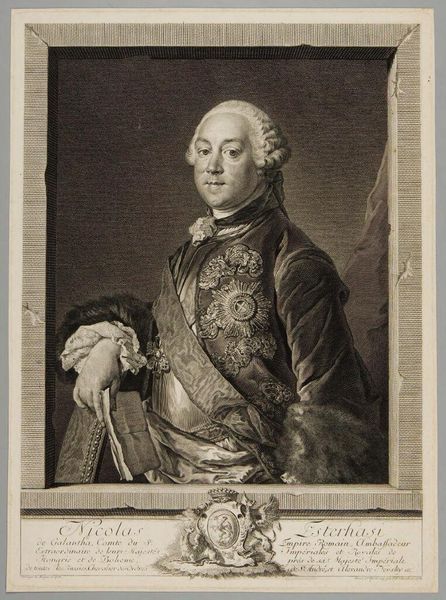

Portrait of Coenraad van Heemskerck, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, Lord of Achttienhoven and Den Bosch 1750

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

character portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

dog

#

portrait reference

#

portrait head and shoulder

#

group-portraits

#

animal portrait

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

genre-painting

#

facial portrait

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

#

rococo

#

digital portrait

Dimensions: height 86 cm, width 67 cm, depth 6 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Mattheus Verheyden’s "Portrait of Coenraad van Heemskerck, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, Lord of Achttienhoven and Den Bosch," created in 1750. It's an oil painting, quite characteristic of the Rococo era. Editor: It strikes me immediately with its blend of formality and, surprisingly, tenderness. The subject is clearly a man of stature, but the way he cradles the dog softens his image. It’s quite an intimate gesture for a formal portrait. Curator: Absolutely. Van Heemskerck's portrait is interesting from a social history perspective. These displays of status through finery and association— note the prestigious title—were crucial to maintaining social hierarchies. Rococo portraits served to idealize and legitimize power. Editor: It's intriguing how the artist tries to normalize these figures through their dogs and convey the notion of having a tender and delicate soul to perpetuate that their high status and social positioning were actually humane. How successful do you think he was at bridging that divide, especially when we consider Verheyden's status as a history painter for the elite? Curator: Well, artistic license always plays a role. It’s important to see how portraiture supported prevailing notions of class. His pose and costume do not invite questioning of his privileges but, simultaneously, are used to create a favorable impression that supports existing structures. The subtle color scheme serves well that agenda. Editor: I agree. Thinking about the dog, it can also symbolize faithfulness, hunting prowess, but it also feels like a tool to further domesticate the public perception of Coenraad. What about the details? The frilly cuffs and gold braid trim signal high social standing without saying it outright. Curator: Yes, precisely. Every element, from the carefully arranged wig to the pastoral landscape backdrop, contributes to a cultivated image of refinement and authority. Editor: For me, the power dynamics inherent in commissioned portraits during this period are so palpable here. Verheyden delivers what was requested, following social conventions of the era and reminding us that these paintings reflect their time's power dynamics. Curator: A fantastic painting overall; looking through this painting gives us insight into social history, painting trends and portraiture altogether, something visitors can carry into the museum’s next room. Editor: I walk away thinking how powerful artworks from past eras, as beautifully executed as this painting, remind us to continually question whose stories and what versions of the world were historically privileged and seen.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.