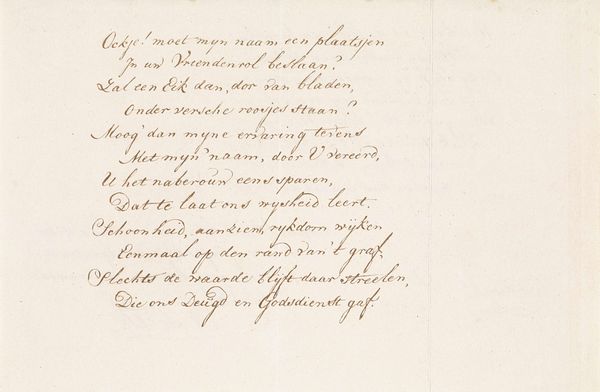

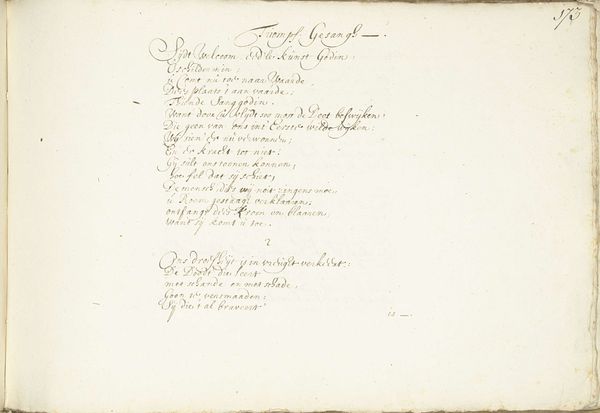

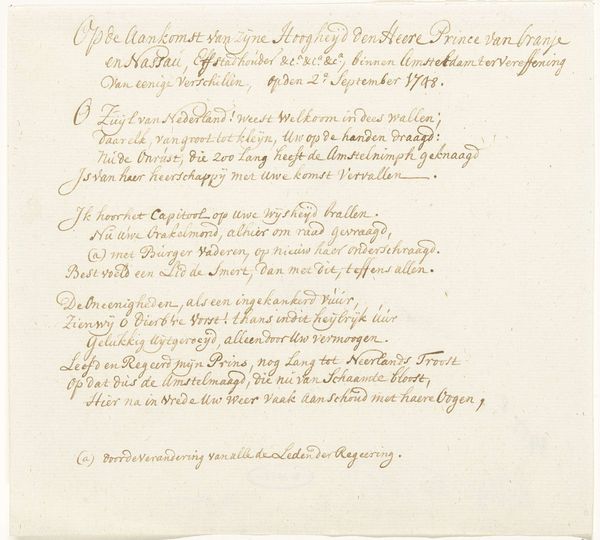

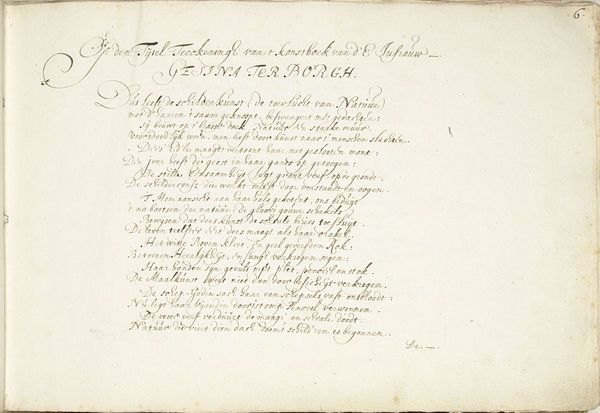

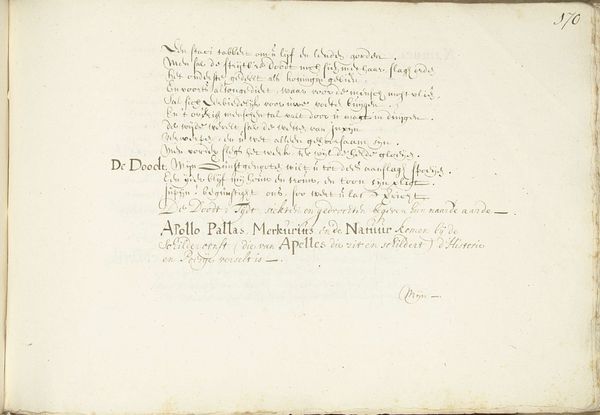

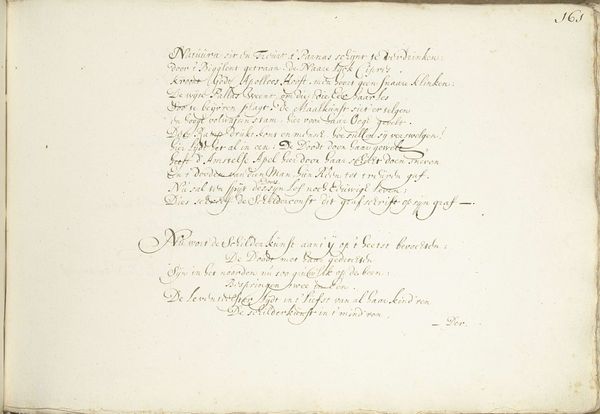

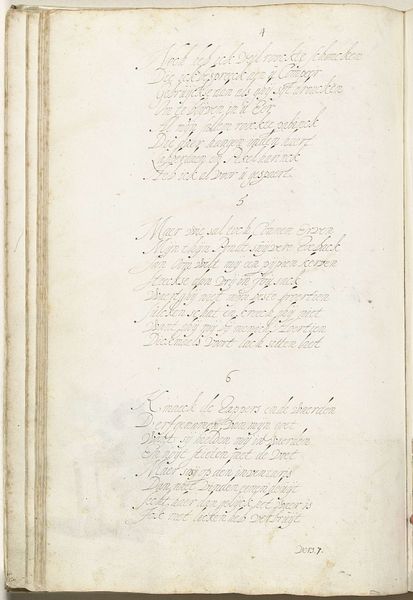

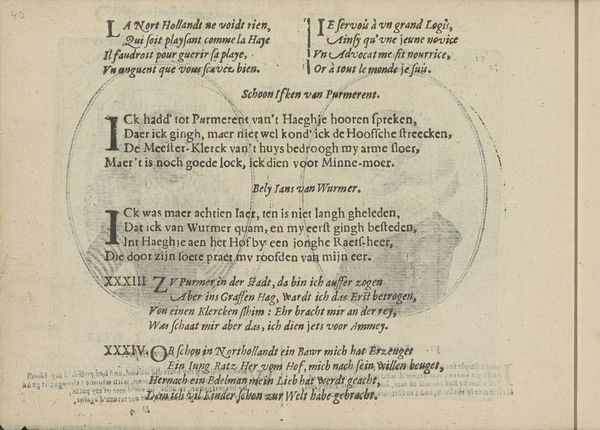

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

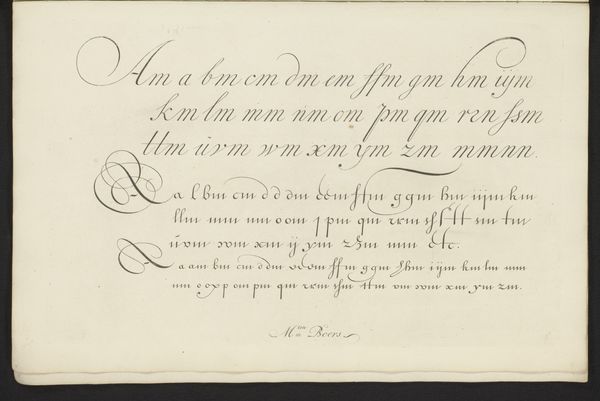

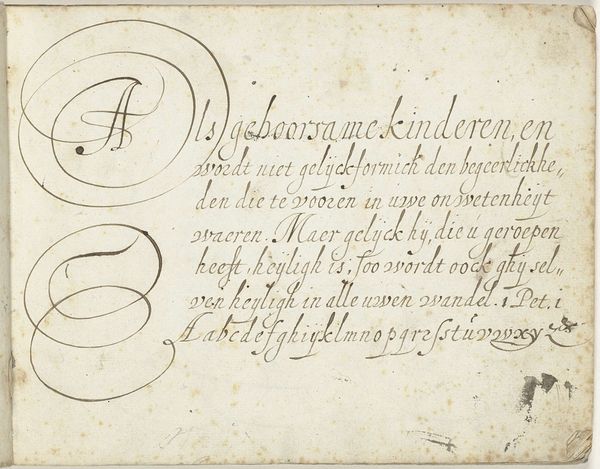

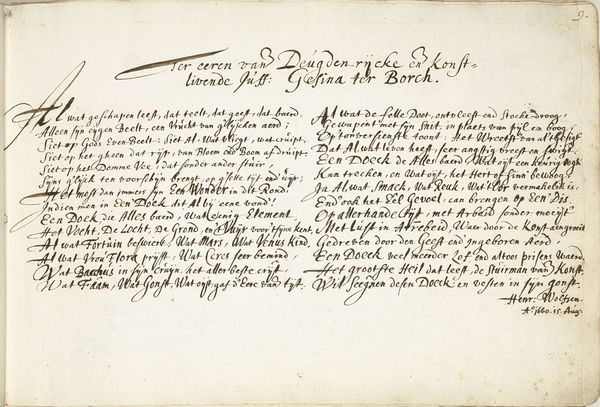

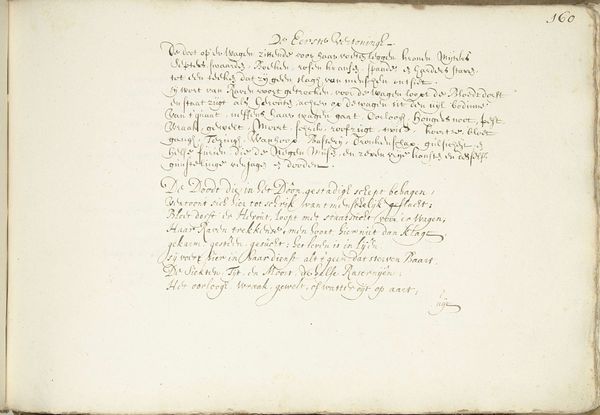

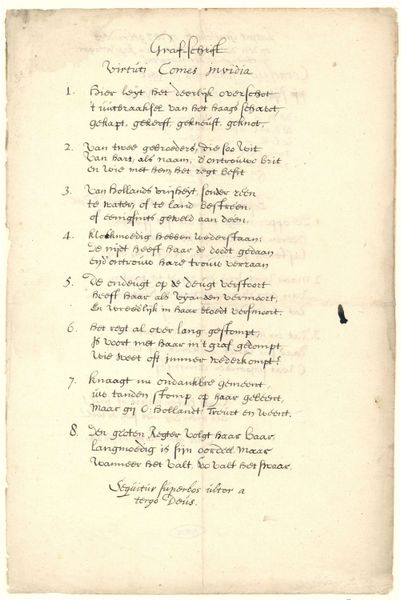

hand-lettering

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

#

old engraving style

#

hand drawn type

#

hand lettering

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 208 mm, height 57 mm, width 40 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intriguing drawing, rendered in ink on paper, is titled "Zittende man die zijn luit stemt," which translates to "Seated Man Tuning His Lute." It's attributed to Gerard ter Borch the Elder, dating roughly from 1620 to 1625. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What's your immediate impression? Editor: Tiny, isn’t it? Like a postcard. Melancholy. There’s a vulnerability to the way he hunches over that lute. A beautiful hand-drawn script accompanies a somewhat humorous caricature of a musician struggling with his instrument, a scene of daily life of the era. Curator: Indeed. Ter Borch was deeply engaged in genre painting. These were images of everyday life, reflecting the rising merchant class of the Dutch Golden Age. What's interesting here is how it blurs the lines—it's almost like a preparatory sketch combined with literary elements. The script adds another layer. Editor: Right. I read that caption at the top: "Niet te Hoog, Niet te Vrooly" or “Neither too High nor too Merry," setting a very specific tone. It's a cautionary, self-deprecating tale, right? About staying balanced? It speaks to that universal musician’s frustration. My own failures keep whispering to me, and suddenly I'm not merry either! Curator: It's open to interpretation, of course, but the placement of the handwritten verses around the sketched figure, alongside his profession as a tradesman and tax collector, places this image within a complex network of socio-cultural factors of the time, beyond just artistic intention. He did also make travel books, though... Editor: A fascinating double life. Tradesman by day, troubadour, poet and philosopher by night? I wonder if it made it hard for his clients to trust him when it was time to pay the dues. Curator: Possibly. I’m not sure how far this was circulated or how it may have helped build social capital, although such a sketch certainly wouldn’t damage reputation or goodwill. But consider the way these smaller, personal artworks functioned within the Dutch art market at the time… Editor: It feels very immediate and personal, doesn't it? I mean, even the ink fading tells a story. Maybe he gave this away as a quirky souvenir. Now I’m picturing some very surprised Dutch burghers pulling this out of their mailboxes 400 years ago. Curator: Perhaps, or a carefully crafted piece destined for a collector’s album, circulating through very different networks. We can’t be sure without better archival data about distribution... Regardless, it’s a compelling little glimpse into 17th-century life and artistic practice. Editor: Absolutely. It’s funny how a tiny ink drawing can echo through centuries. You start tuning the lute, and you end up touching eternity. Or maybe just getting slightly less grumpy. Either way, I'm off to practice my scales.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.