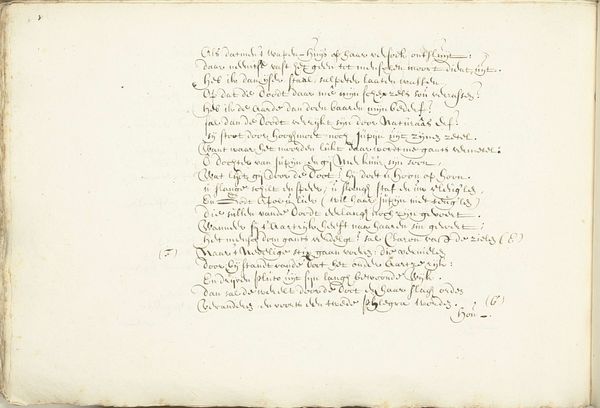

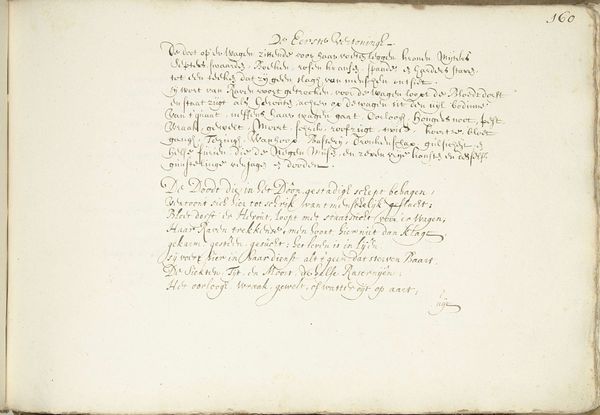

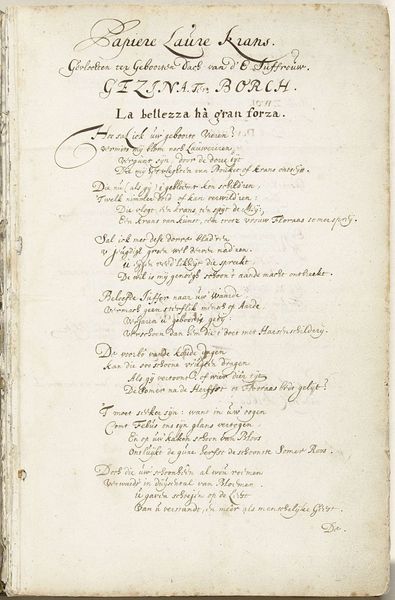

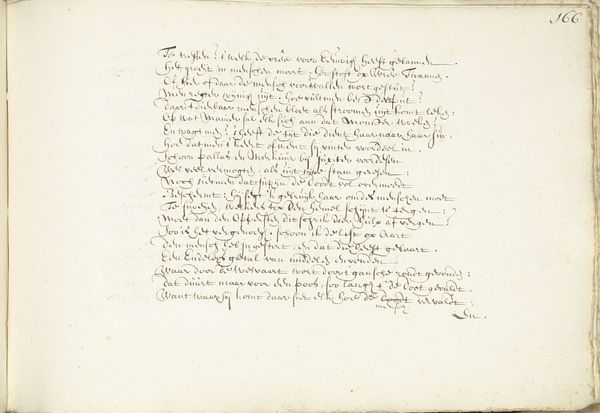

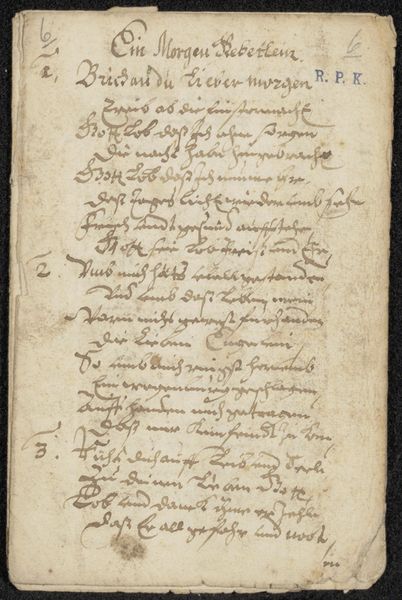

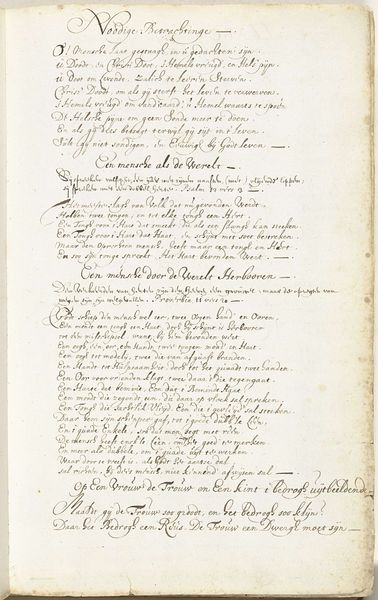

drawing, textile, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

textile

#

paper

#

ink

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: height 304 mm, width 202 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

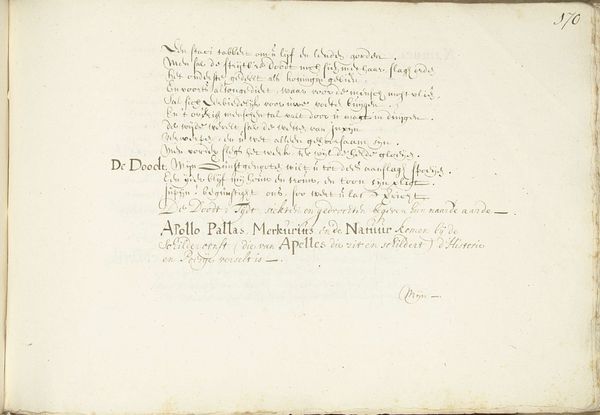

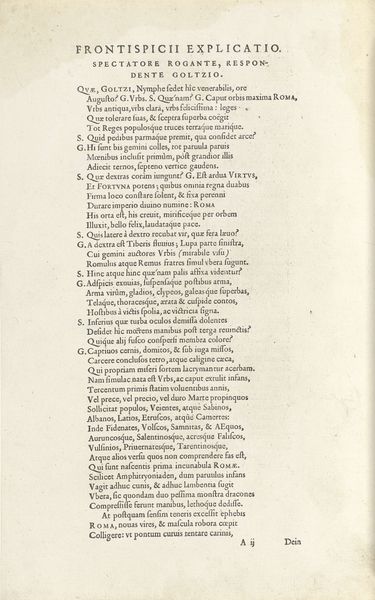

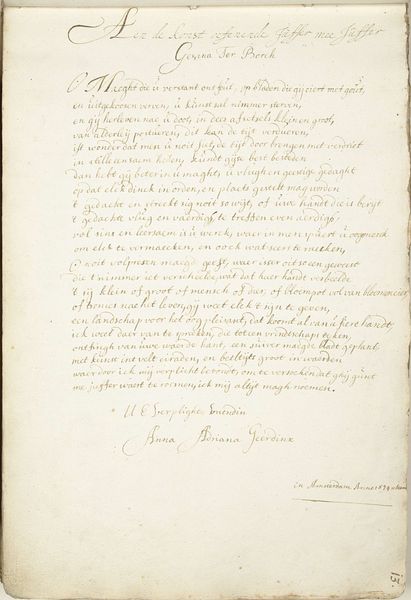

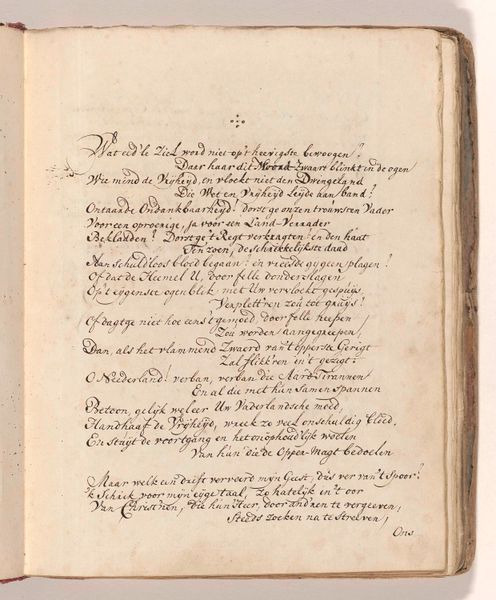

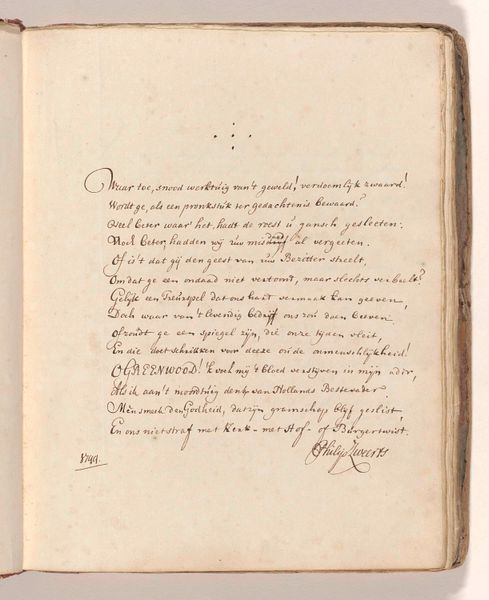

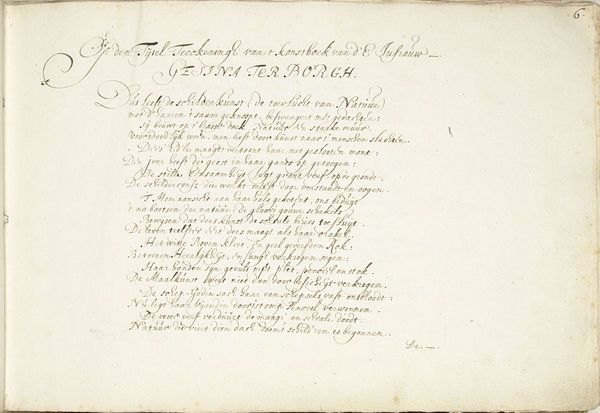

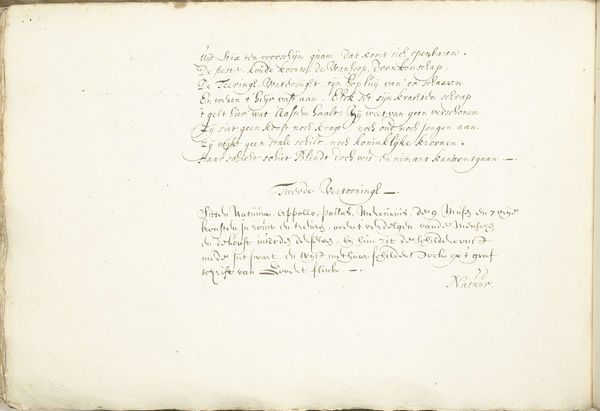

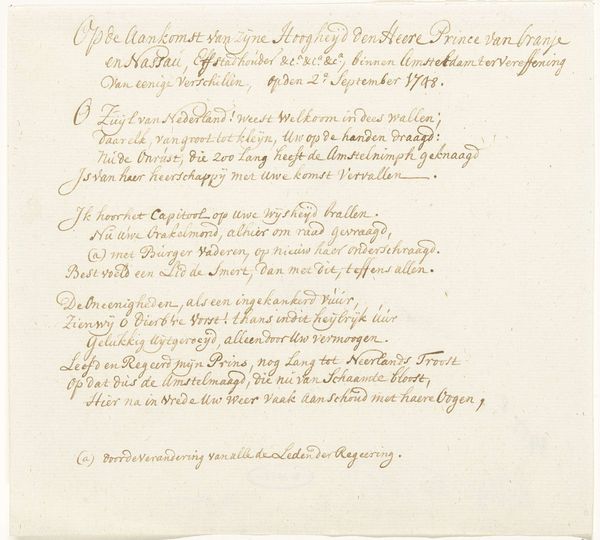

Curator: This is "Grafschriften op de gebroeders De Witt, 1672," dating from between 1672 and 1699, now held at the Rijksmuseum. The piece consists of ink on paper and textile. It's an anonymous broadside memorializing the De Witt brothers. What are your initial impressions? Editor: Stark and sobering. The tight, cramped calligraphy conveys a real sense of urgency and perhaps even suppressed rage. It’s raw, unpolished, like a hastily written lament. The slight yellowing of the paper only intensifies the feeling that it’s a direct artifact of a brutal time. Curator: Indeed. The De Witt brothers' lynching was a political earthquake. This broadside, filled with poetic indignation, offers a glimpse into the intense emotions of the period. The use of Dutch rather than Latin tells us it was aimed at a popular audience. Editor: Notice how virtue is invoked at the beginning— "Virtuti Comes invidia," which could be translated as "Envy is the companion of virtue." This signals immediately that the writers viewed the De Witts as virtuous men destroyed by jealousy and political machinations. Curator: Exactly. The symbolism isn’t subtle. These poems decry the barbarity of the act, accusing Holland of ingratitude and faithlessness. The image of enemies rending flesh… it’s a vivid attempt to cement a particular interpretation of events in the public consciousness. Editor: That phrase, “Knaagt nu ondankbre gemoent", "Now gnaw, ungrateful community," really hits hard. It’s a complete reversal of typical civic pride, depicting the nation itself as a ravenous, unfeeling beast. The script lends itself to a furious scream on paper. Curator: Broadly distributed poems such as these, visually immediate through their graphic typography and potent iconography, helped transform the De Witts into martyrs for a certain political faction. Memory made through art, quite effectively. Editor: It definitely prompts us to reconsider the fragility of reputation and how swiftly public sentiment can turn. This is less a formal portrait and more a visceral cry of protest against injustice—one that still resonates centuries later. Curator: I see it similarly, this serves as an emotional record which allows us to consider its meaning and effect upon 17th century society. Editor: Agreed, now it sits inside a modern-day context which is a strange place for something of this nature, given its intended use at the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.