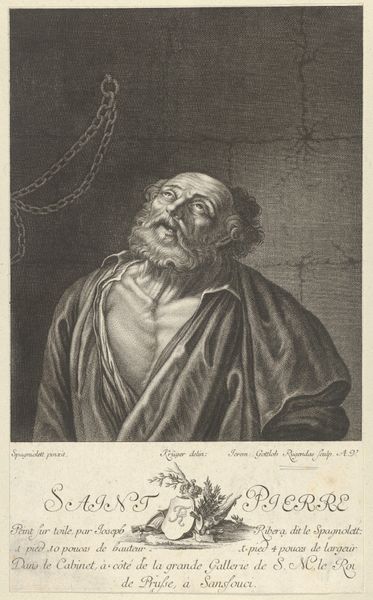

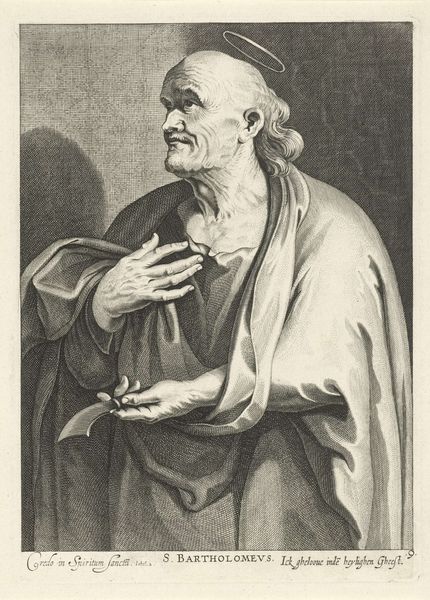

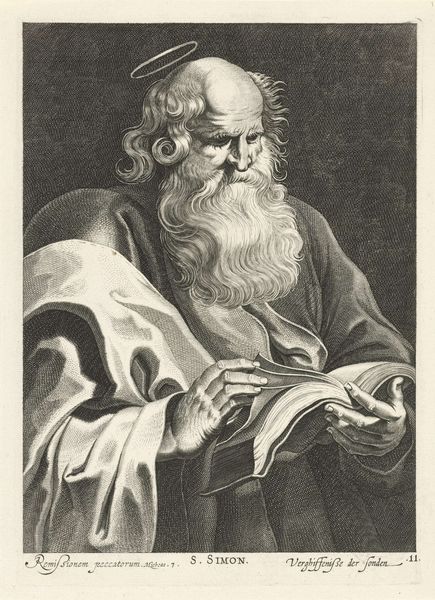

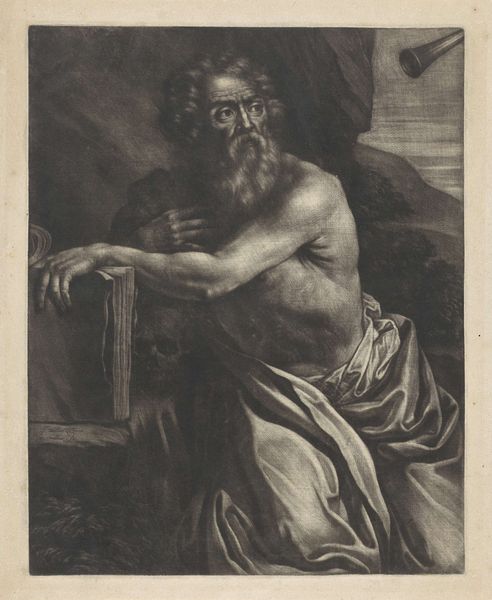

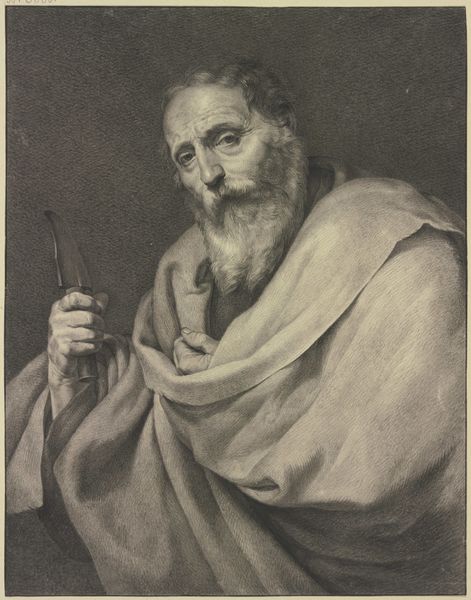

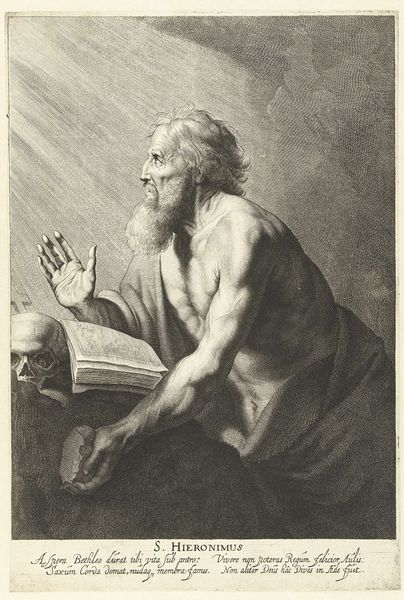

drawing, print, engraving

#

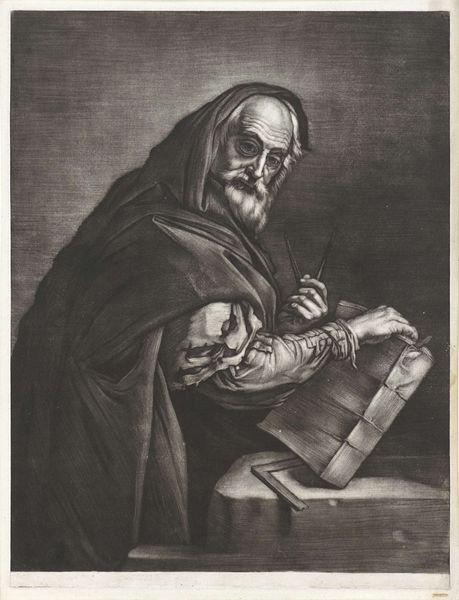

portrait

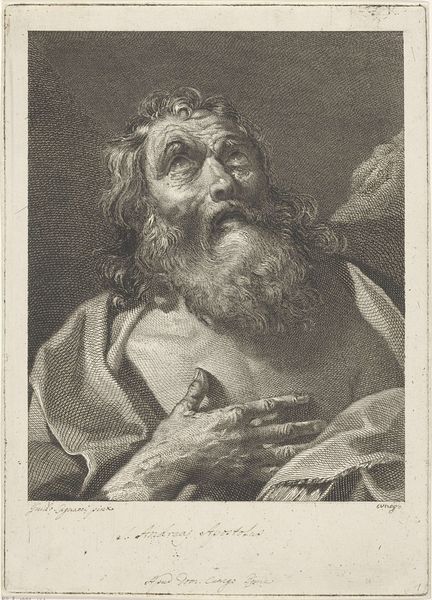

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

portrait art

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 3/16 in. × 8 in. (23.4 × 20.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

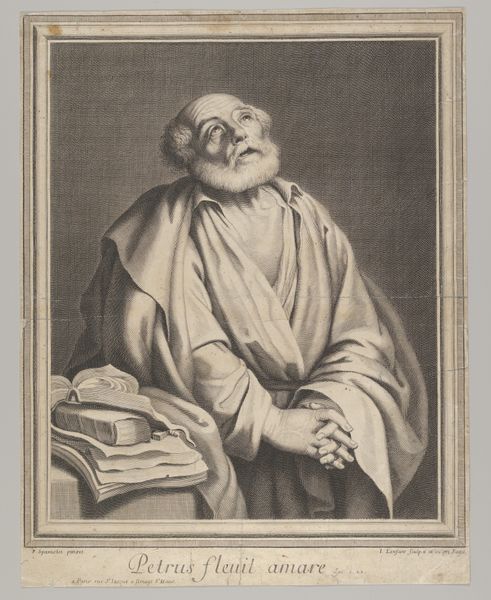

Editor: So, this engraving from around 1735-1745 is titled "The Penitence of Saint Peter." It's currently housed at The Met and attributed to Jeremias Gottlob Rugendas after a painting by Jusepe de Ribera. I’m immediately drawn to the somber mood – Peter’s gaze is intense. The rendering of the face looks remarkably soft for a print. What’s your initial take? Curator: The first thing that catches my eye is that upward gaze. It’s not just sadness, is it? There's a yearning, a reaching. The old boy's practically pleading with the heavens. Now, given the context—Peter denying Christ—think about the weight of that denial. The books he rests his hands on aren't just props; they're a symbol of knowledge, of scripture, now stained with his betrayal. What does contrition look like, feel like? I imagine it probably stings the soul. Editor: That makes so much sense! The books had almost receded into the background for me, but knowing the narrative, it’s obvious how powerful a symbol they are in this context. It's interesting how a medium known for precision still lets through something like raw emotion. Curator: Raw indeed! It is a copy of painting by Ribera, though, and an engraver – especially one of Mannl’s caliber – wouldn’t just replicate the *image*, he'd strive to capture the *feeling*, right? Consider the almost theatrical lighting here – what they called tenebrism – it isn’t just about showing off skill; it amplifies that interior turmoil, don't you think? Editor: Absolutely, that sharp contrast really intensifies the drama. I initially viewed it as just a formal element, but I see now how crucial it is to understanding the emotional weight of the piece. Curator: That's art history for you. A dance between skill and intention! What an interesting moment it captures; it really digs at that complicated intersection of faith, fallibility, and forgiveness. I feel like I understand Peter a little better now, flaws and all. Editor: Yeah, that's amazing. It shows how just one expressive work can say more than any sermon ever could!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.