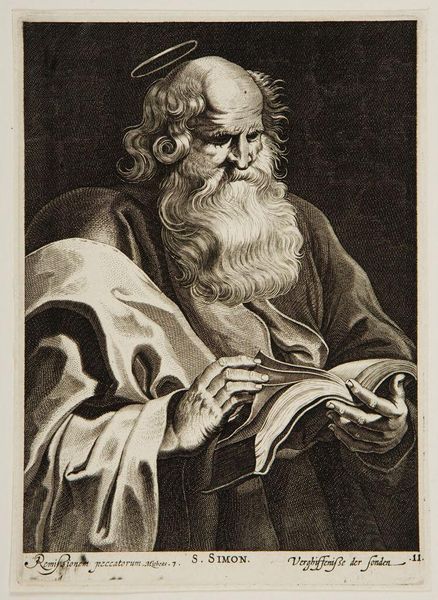

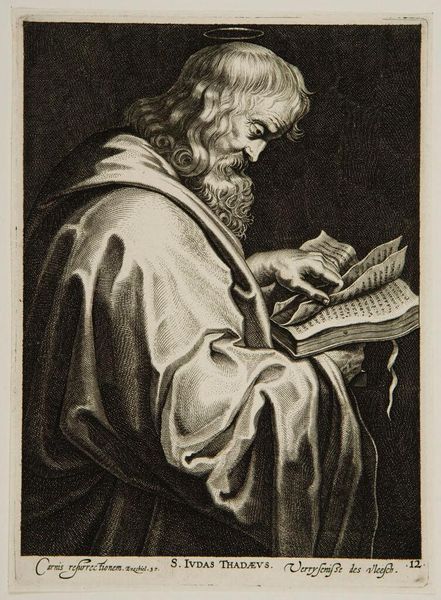

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

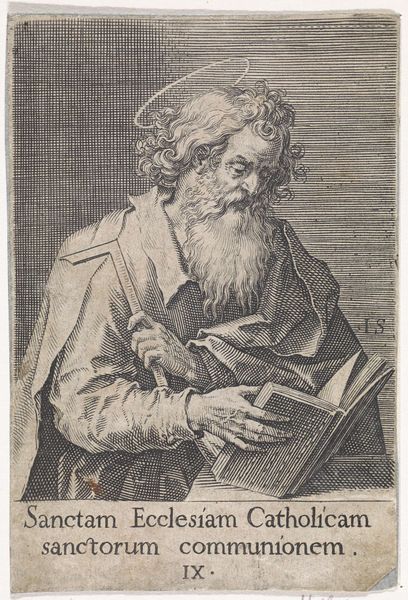

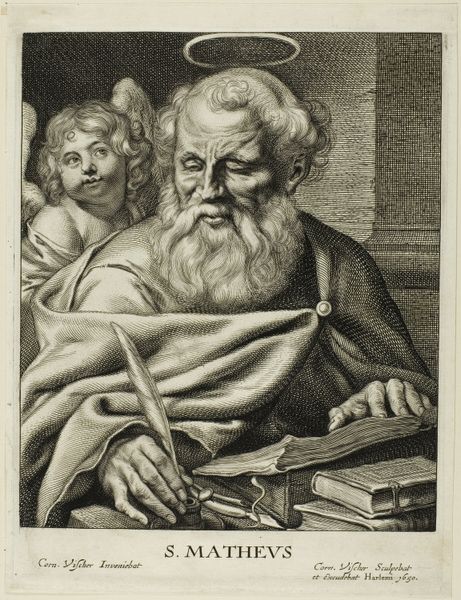

Curator: This engraving, entitled "Apostel Simon," by Nicolaes Ryckmans, was likely created between 1616 and 1636. It resides here with us at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you first about it? Editor: The intense focus. Look at the deeply etched lines around his eyes and mouth. It's almost palpable, the weight of whatever he's reading, you can practically feel the texture of that aged paper between his fingers. Curator: Ryckmans was working within a specific visual language. Engravings like these, circulating widely, played a critical role in shaping religious and historical narratives. Editor: It’s also fascinating to consider the tools Ryckmans employed to produce the prints and the physical labor involved in crafting this image. Curator: Precisely, engraving served as both a reproductive medium and an artistic form in its own right. Ryckmans could disseminate these images far and wide, amplifying their socio-political influence during that era. It’s worth thinking about how easily reproducible this engraving is compared to, say, painting with oils. Editor: And the material longevity of prints! Think of how many hands this piece has passed through, all those viewing contexts. Do we know the quality of paper used for different print runs? The price? These small details help paint a broader social and material history. Curator: Absolutely, the affordability and portability of these engravings democratized art to an extent. This work engages with established religious imagery, tapping into an existing iconography. Editor: You're right. He presents Simon as almost working-class though; more everyman than icon, more a physical being of labor than holy image. He looks more carpenter than a biblical saint to be sure! Curator: In a sense, this engraving bridges the gap between the sacred and the accessible, bringing religious figures closer to the everyday viewer. These prints brought faith into the household, into the quotidian, blurring lines that separated religious institutions from everyday individuals. Editor: Exactly. It provokes consideration of who consumes such works and how materials intersect with that social dynamic. Curator: A reminder that we’re not simply dealing with images but rather material objects carrying potent ideological weight. Editor: And crafted through a physically laborious and complex production, something easily lost in viewing this nearly half a millennia after it was made.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.