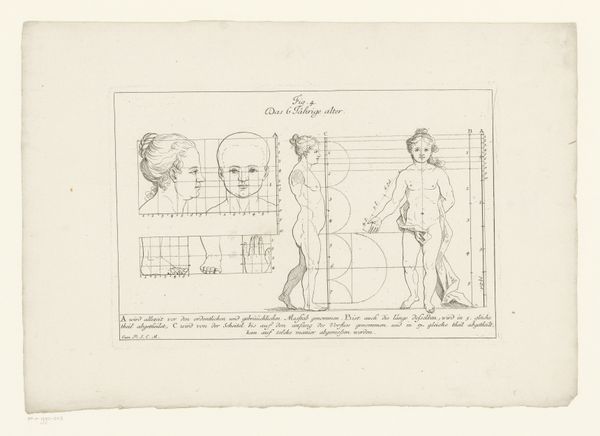

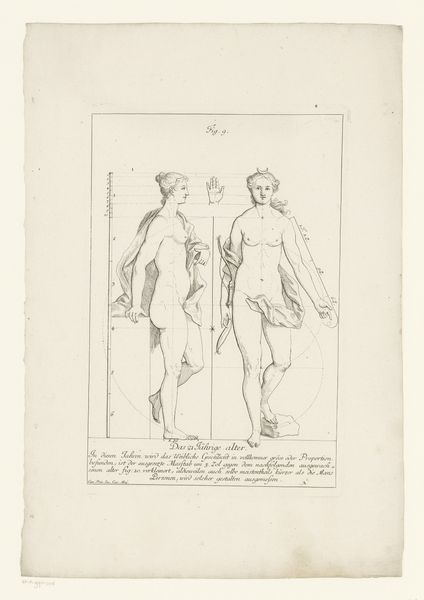

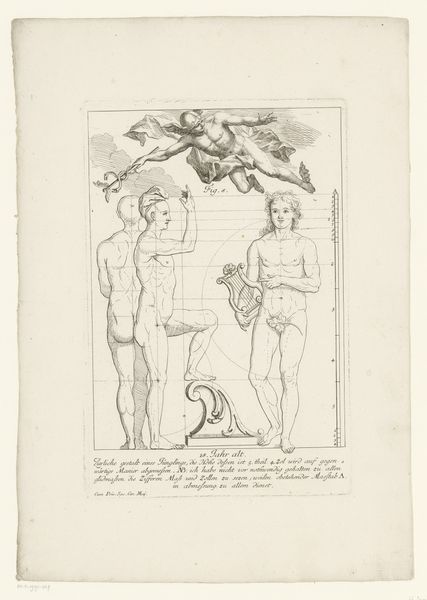

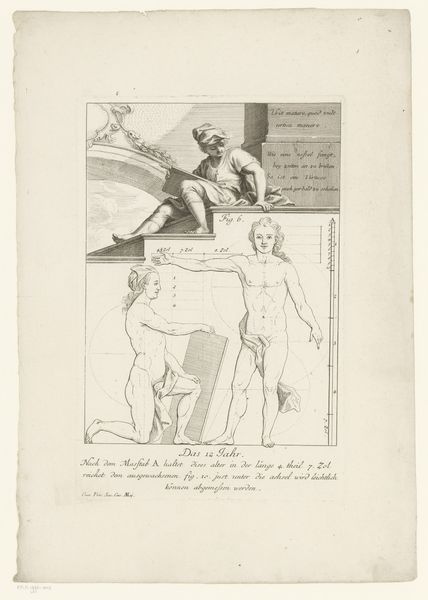

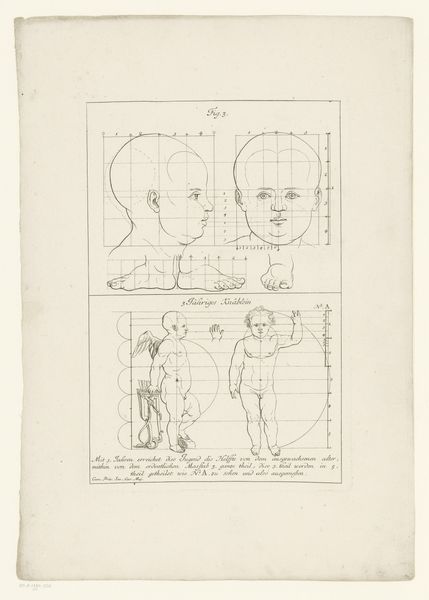

Drie aanzichten van het lichaam van een negenjarige jongen 1723

0:00

0:00

hieronymussperling

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

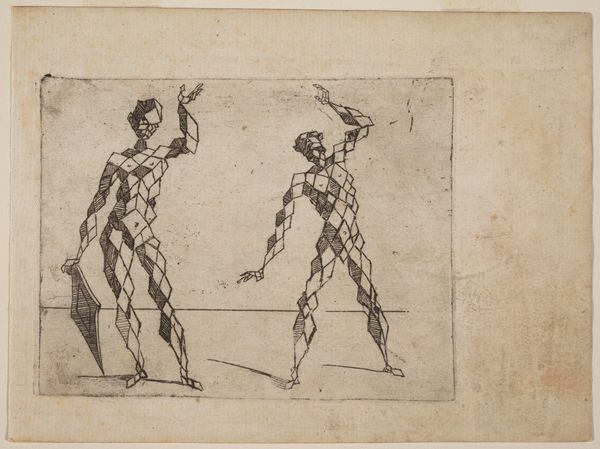

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

classical-realism

#

perspective

#

figuration

#

paper

#

form

#

ink

#

geometric

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 315 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

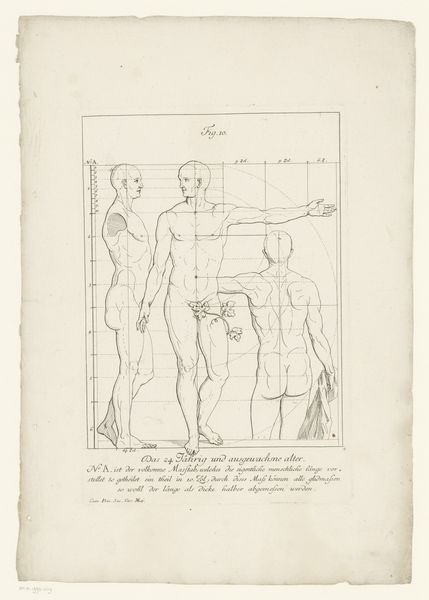

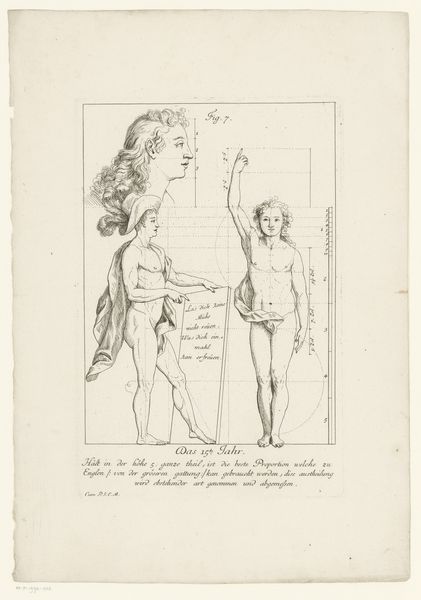

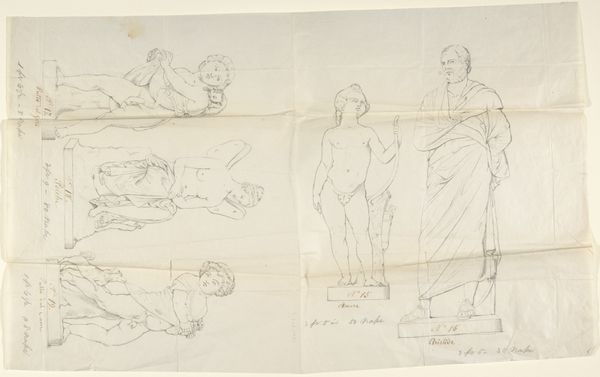

Curator: Before us, we have an intriguing drawing entitled "Three Views of the Body of a Nine-Year-Old Boy," created by Hieronymus Sperling in 1723. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's stark, almost clinical. The figures, rendered in precise ink lines on paper, remind me of architectural blueprints or a scientific illustration. It looks like it’s designed to convey factual data about proportion, rather than an emotive observation of a person. Curator: Indeed. Sperling seems to have created this as an academic study. In its time, these drawings played a crucial role in the education of artists, serving as models of ideal human form. Editor: Note how the repetitive representation denies the individuality of the boy; there are no observable characteristics or distinguishing features other than ideal proportions and geometries of the human form. The labor and detail needed for this—the multiple views, the calibration and mathematical references—highlight how bodies became commodities for artistic consumption and scholarly pursuits, effectively stripping them of agency. Curator: I think you bring up a fascinating and deeply challenging point regarding agency. Yet it's important to consider this work in its socio-historical context, as nude studies were typical, especially during academic training for young artists in the Baroque period. This piece probably represents both the idealization of the human form, aligned with classical ideals, and potentially, a certain kind of scientific objectification that rose with The Enlightenment and associated belief in objectivity. Editor: Even that pursuit of the “objective” speaks to material reality! Artists don't work in a vacuum. Sperling needed ink, paper, studio space—these drawings were part of the network of production in his time. Even the choice of model has ramifications of class and power that the final piece presents with neutrality, which demands scrutiny. Curator: That’s a wonderful reading of this piece. Ultimately, this work serves as a complex document revealing intertwined ideals regarding science, form, and perhaps even class during the early 18th century. Editor: Agreed. Sperling’s engraving certainly provides ample context for pondering how images both reflect and construct realities—both physically and socially.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.