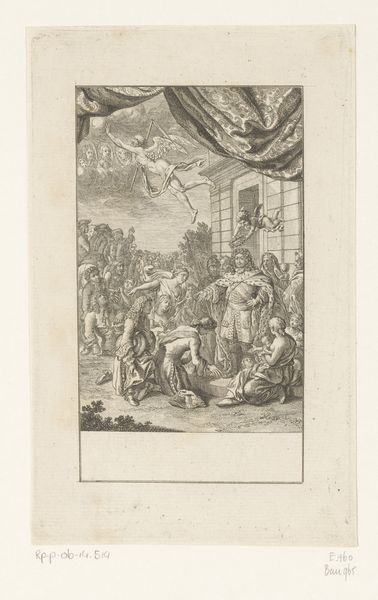

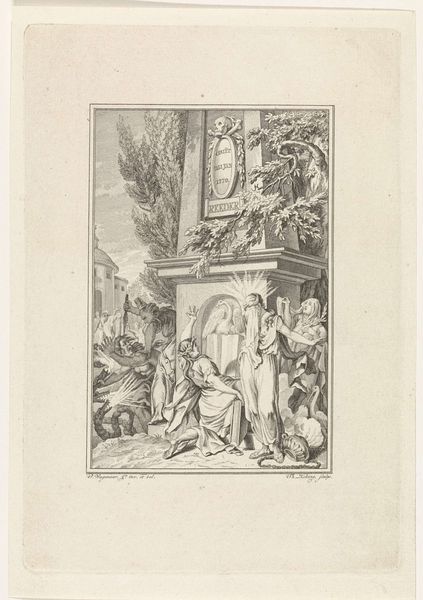

Christus geneest een bezeten man en een bezeten man die niet kon spreken before 1732

0:00

0:00

gabrielhuquier

Rijksmuseum

print, etching, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 197 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is an etching created by Gabriel Huquier, dating to before 1732. The Rijksmuseum holds this print, titled "Christus geneest een bezeten man en een bezeten man die niet kon spreken"—"Christ heals a possessed man and a possessed man who could not speak." Editor: My first impression is one of controlled chaos. The composition is teeming with figures, and despite the classical architectural backdrop, there's a palpable sense of drama. The line work is exquisite in places but feels frenetic overall. Curator: I agree; the baroque aesthetic certainly lends itself to that frenetic quality. If we observe closely, the artist utilizes line weight and density to create tonal variations. The contrast between the light emanating from Christ and the shadows clinging to the figures heightens the emotional intensity of the scene. We can appreciate the way he creates visual interest in the drapery, observing it fluttering around these figures, imbuing the work with motion and depth. Editor: That light isn't just a formal element; it's the key signifier. Consider the socio-political context. This image emerges from a culture grappling with concepts of madness, illness, and divine intervention. What power structures are being reinforced here? Is this a compassionate depiction or one that pathologizes difference and relies on religious dogma? Curator: Perhaps both. The rendering of Christ does follow certain visual codes: his hand gestures, his light halo, which is the conventional iconography that speaks to divinity, healing, and benevolence. From a purely formal perspective, it serves as the focal point that helps draw the viewer's eye into the dense pictorial space. Editor: True, the divine light has significance. But look at the individuals at the bottom, writhing as their alleged demons are exorcised. I can't help but think of the very real, very human suffering being visualized, especially when considering the social implications related to public health and community well-being at this time. It evokes empathy but also demands critical consideration of power and social control. Curator: Your reading brings forward very valid observations, shifting our consideration of Huquier’s compositional strategies. Looking at this work, from a perspective of compositional style or sociopolitical considerations, encourages us to engage with 18th-century visual rhetoric and invites important observations about those times. Editor: Absolutely, understanding that visual rhetoric helps us question its underlying messages, especially as they might perpetuate marginalization and social stigmas. The print challenges us to look deeper and to question who benefits from such depictions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.