Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 173 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

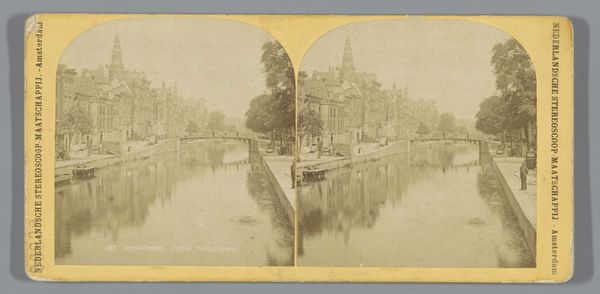

Curator: This is a photograph entitled "Grimnessesluis, Amsterdam" captured by Pieter Oosterhuis, dating back to sometime between 1855 and 1868. It’s an albumen print. Editor: It's sepia-toned and ghostly... almost ethereal, though clearly depicting a constructed urban environment. It makes me think about the relationship between the city and memory. Curator: Indeed, the albumen process would involve coating paper with egg whites and then silver nitrate, resulting in a print with a fine tonal range. The labour-intensive practice of preparing the photographic paper, hand-coating, sensitising, and developing each print gives each print unique variations and artisanal value. These cityscapes, often sold as souvenirs, document the rapid modernisation occurring across European cities in this era. Editor: And this location, Amsterdam, offers rich context. The architecture and waterways immediately suggest its mercantile history, deeply tied to colonial trade routes and systems of labor exploitation. I'm drawn to the stillness of the water, reflecting the buildings – perhaps suggesting a mirroring of the city's past and present? Curator: That reflection speaks to photography’s perceived truthfulness in this era, its ability to capture material reality precisely. Think of the workers involved: constructing those buildings, maintaining the canals, ferrying goods—their unseen labor is crucial. This photograph also underscores the evolution of visual consumption during the rise of industrialisation and photography. Editor: It's romantic, sure, in its aesthetic presentation, but it serves as a potent reminder of the layered history—economic, social, political—embedded in every street corner. It brings into focus urban development's undeniable, and often overlooked, inequalities, showing how access and place were distributed in society, then and now. Curator: Absolutely. Focusing on how Oosterhuis actually created this image reveals the labour and materials, grounding what may seem like a straightforward representation in its messy material and economic conditions. Editor: Looking at this work now makes me think of gentrification, displacement, and how we document these processes—who gets to tell these stories? Curator: I appreciate that reflection; it demonstrates how even what seems to be straightforward visual documentation is also inevitably woven into broader material conditions of labor and capital. Editor: And that's how engaging with the historical context surrounding this photographic print opens it up for considering power dynamics and histories of oppression that are still relevant.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.