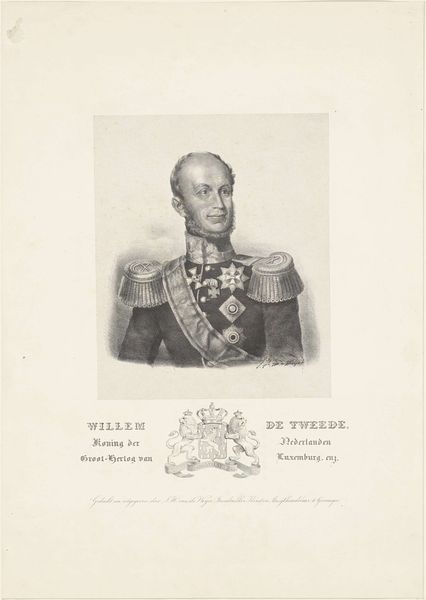

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

old engraving style

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

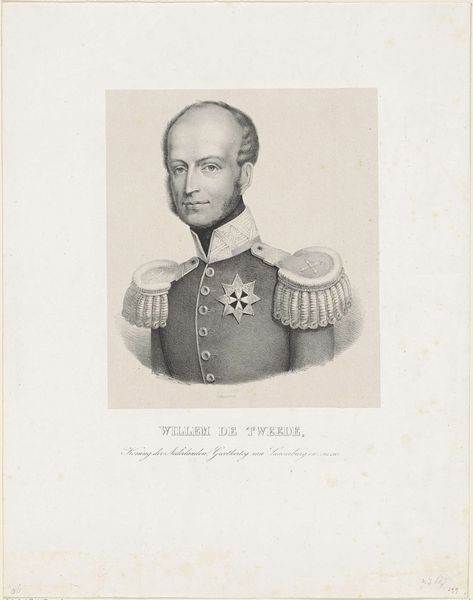

Dimensions: height 227 mm, width 163 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a portrait of Willem II, King of the Netherlands. It's rendered in pencil, created between 1849 and 1882 by Hendrik Wilhelmus Last. The piece gives off quite the formal air, doesn't it? Editor: It does! My initial impression is how rigid the portrayal is. The tight lines and limited shading give it this almost…stark feeling, despite the subject's attempts at a benevolent expression. It’s interesting to think about what statements it aims to make regarding authority. Curator: Indeed. As a portrayal of power during the 19th century, this type of image served specific social and political functions. الرسم Portraiture became intertwined with nationalism and solidifying royal imagery within a burgeoning modern state. It depicts the King with symbols of status—military attire, medals— all aimed to project control. Editor: But to whose benefit, right? We should also recognize the image as constructing not only a figure of authority, but how systems of governance were upheld. Those frilly epaulettes aren't just decorative; they're visual shorthand for institutional might built on military structure and colonial enterprise, aren’t they? Curator: Precisely. Last captures King Willem II during a period of great change in the Netherlands. After Willem's more conservative early reign, he eventually conceded to constitutional reforms—important when assessing public perceptions and legacy, which an image such as this portrait undoubtedly would play a part in influencing. Editor: It invites reflections about constructed images and their impact, particularly now. In that way, images such as this allow an avenue into historical dialogue about power relations, visual propaganda and whose interests are being catered to by formal representations such as these. It makes one think who has control over not only their own image, but of how those images get manipulated once released into the world. Curator: And those images tell their own story about our past, for better or worse. Editor: Leaving open for a deeper investigation and interrogation of the portrait’s narrative!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.