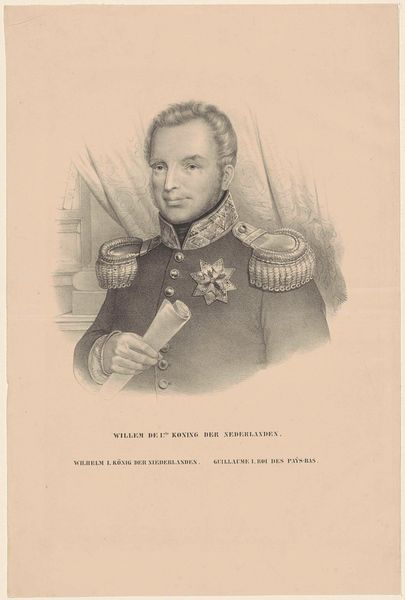

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 303 mm, width 241 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

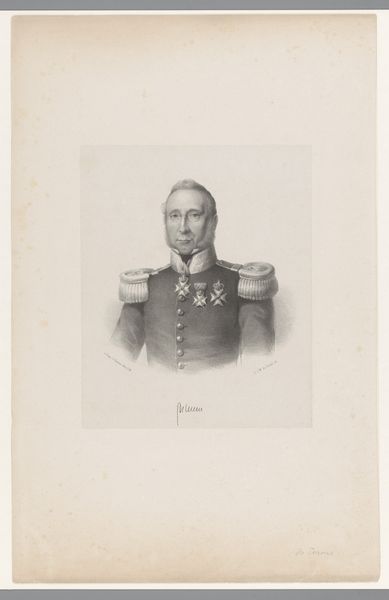

Curator: Here we have an engraving dating back to 1838, titled "Portret van Willem I Frederik, koning der Nederlanden," a portrait of King William I of the Netherlands. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its formal, almost severe character. The greyscale lends it a somber quality. The line work seems incredibly precise, emphasizing the rigidity of the king's attire and posture. Curator: Indeed. Notice the deliberate composition, enclosed within an ornate oval frame, surmounted by the royal crown. This echoes the Neoclassical principles that governed much academic art during the early 19th century, focusing on order, balance, and idealization. Editor: Precisely, but look closely at the physical labor involved in creating those meticulously etched lines. Think of the artisan, painstakingly working the metal plate to reproduce this regal image. There is the human effort, the tooling and the making involved in propagating power across the kingdom. This wasn't about celebrating the *person* of the King. This was about multiplying the power he held as sovereign and flooding society with that signal. Curator: Interesting. I agree the materiality impacts our reading of the image. Considering that engraving allows for the reproduction and wide distribution of the King's likeness is fundamental to understanding the image and its original context, it shows the crown working directly to shape a carefully conceived symbolic projection of power. Note how he gazes confidently outward. Editor: Yes! It’s the mass production aspect I find compelling. Each print would carry that same weight of symbolism, intended for circulation and, ultimately, consumption. We may want to think about that framing from the perspective of those that worked and traded on this item's existence in Dutch society at the time. This wasn't one artist's creation in solitude: its reproduction has far-reaching implications on the communities making a living making art in Dutch society in 1838. Curator: Your observations shift our focus toward a much broader historical understanding. It serves as a potent reminder that the image and production process of even an apparently straightforward portrait hold diverse meanings that shift and transform. Editor: It invites us to look past the regal subject and see the hidden histories etched within the print's production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.