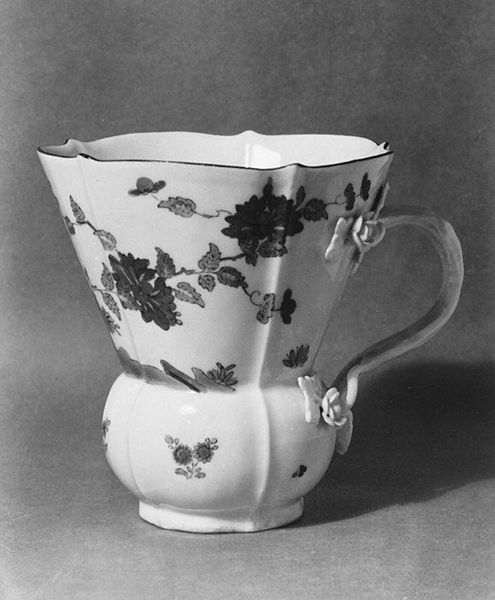

ceramic, porcelain, sculpture

#

ceramic

#

porcelain

#

sculpture

#

decorative-art

#

rococo

Dimensions: Height: 3 in. (7.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have a porcelain cup, likely from the Saint-Cloud factory, dating from 1705 to 1725. The decorative elements give it a regal, if subdued, air. How might we interpret its presence in a collection like the Met? Curator: Think about the power dynamics inherent in the everyday objects of the 18th century. This isn't just a cup; it's a symbol of trade, colonialism, and class. Porcelain production in Europe was fueled by access to resources and technologies extracted from other parts of the world. How does that understanding shift your perspective on the cup's "regal air"? Editor: It definitely complicates it. The cup now feels like a representation of exploitation as much as elegance. Does its delicate design intentionally mask these issues, or were these issues perhaps invisible to its original owners? Curator: That's the question, isn't it? The Rococo style, with its emphasis on ornamentation and pleasure, often served to obscure the harsh realities of the era. Consider the elaborate rituals surrounding tea drinking during this period. Who was included, and more importantly, who was excluded from these spaces of privilege and leisure? And what role did objects like this cup play in solidifying those social boundaries? Editor: So the cup becomes a lens through which to view the unequal distribution of wealth and power in the 18th century. Curator: Precisely. And by examining these objects critically, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complex historical forces that shaped our present. It also prompts us to think about the ethics of display and collecting these objects in contemporary museums. Editor: That's a powerful point. I'll never look at a teacup the same way again. Curator: That's the goal. Art should challenge us to confront the uncomfortable truths of the past and present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.