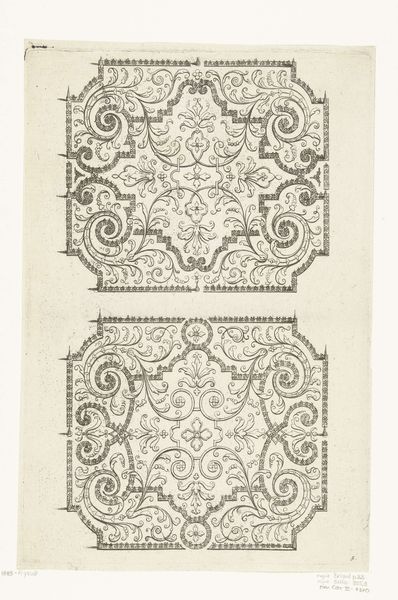

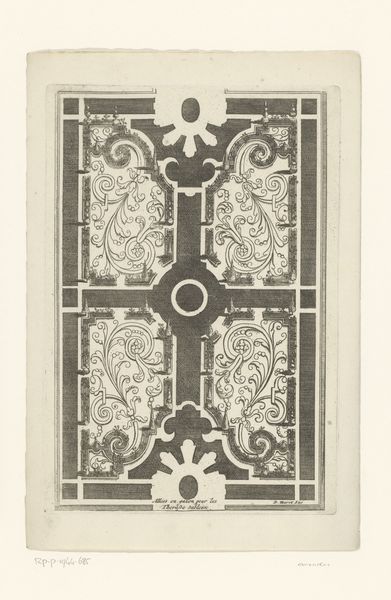

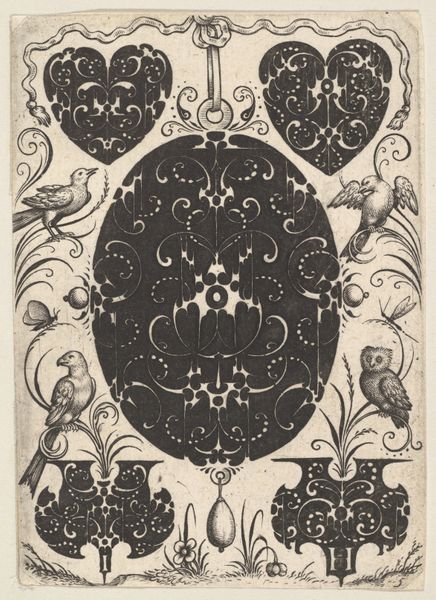

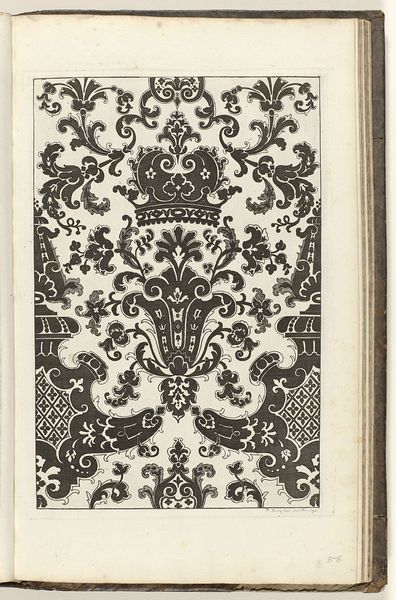

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

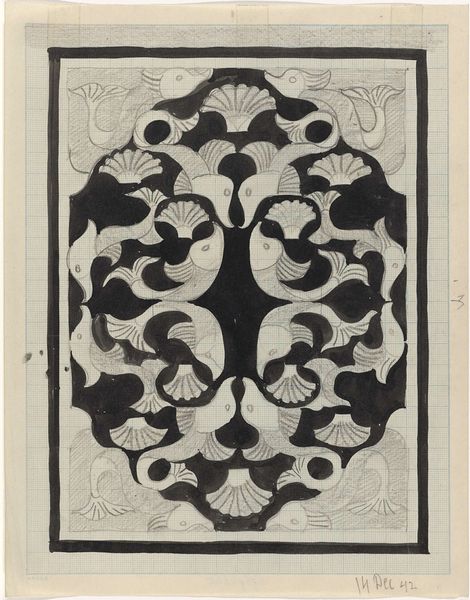

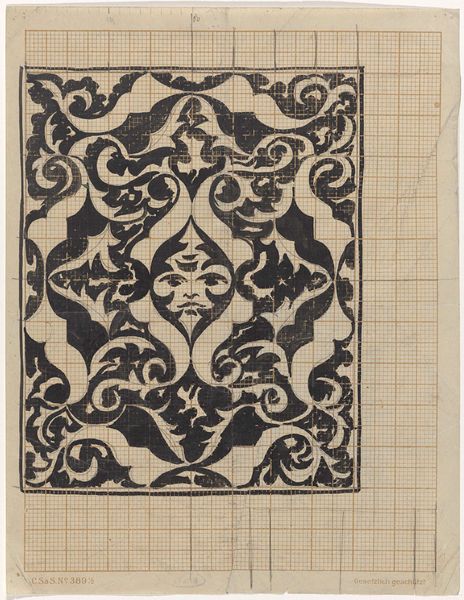

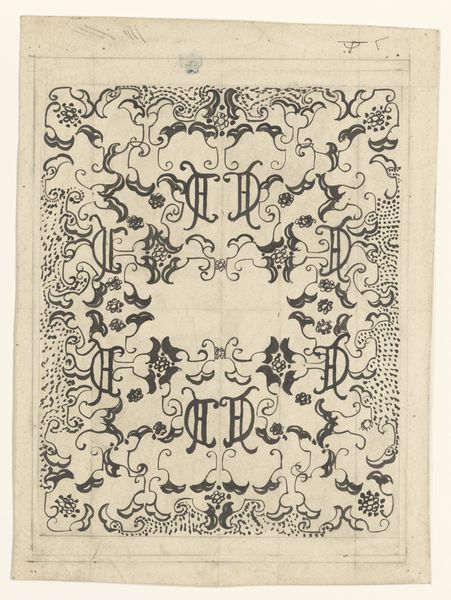

drawing

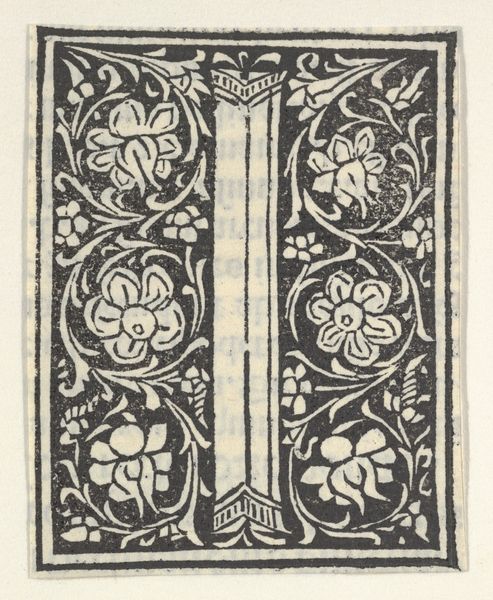

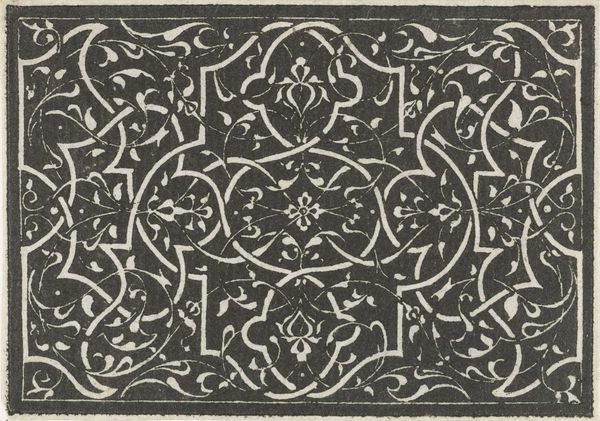

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

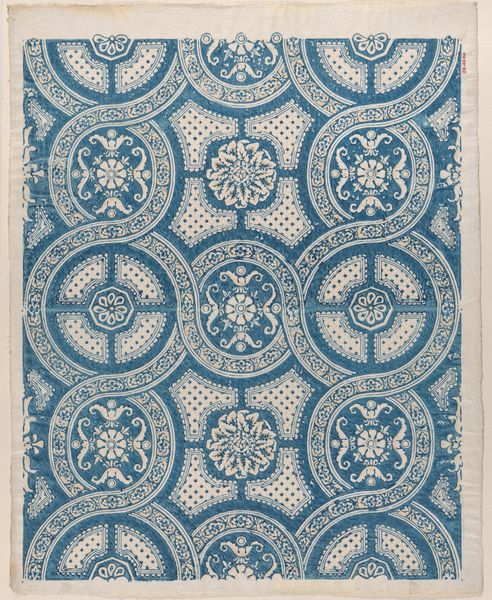

paper

#

geometric

#

pen work

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 287 mm, width 194 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a print called “Plan van tuin met negen parterres” which translates to "Plan of garden with nine parterres" made before 1800, the print on paper employs engraving techniques. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What’s your initial take on it? Editor: I’m immediately struck by its formal, almost rigid structure, but it's tempered by these organic, flowing details within each section. It reminds me of lacework. A sense of ordered control married to free expression... Curator: Precisely. Parterres, these formal garden designs, were immensely popular among the European elite. The symmetry and geometric layouts, meticulously planned, served as a display of power and control over nature and, by extension, over their domains. Editor: Yes, the garden, as a means of expressing dominance and wealth. Beyond that, one must remember that landscapes, during periods of empire, acted as a potent backdrop for colonialism, justifying land appropriation by framing colonized territories through constructed aesthetics that obscured indigenous history and land use. Curator: That’s a vital consideration. These designs, intended for pleasure and aesthetics, also underscored social hierarchies. This wasn't a space for the common person. Its precise execution would have required considerable labor, further emphasizing that hierarchy. We're also looking at the very notion of idealized space in early modernity. Editor: And an erasure, possibly, of any kind of wilderness! I find it somewhat fascinating and terrifying that human imposed constraints on what nature can be extends far beyond just the literal design, impacting even our imagination of nature and landscapes. The highly stylized vegetal forms don't particularly evoke growth to me but frozen ornamentation. Curator: An excellent point. It does represent an ambition, an intellectual pursuit manifested physically on land; an artificial pastoral. What stands out, for me, is how a simple print encapsulates grand ideas around power, social order, and humanity’s place within the natural world. Editor: For me, it speaks to the complex ways in which landscape, even in its idealized form, becomes a stage for performing identity and power. Considering how design and environmental history intertwine allows us to reflect critically on what visions of landscapes we wish to endorse today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.