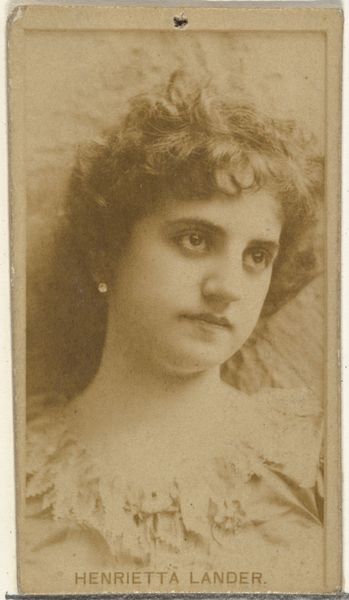

Jeannette Lowrie, from the Actresses series (N245) issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes 1890

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 1/2 × 1 7/16 in. (6.4 × 3.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So this is "Jeannette Lowrie," a gelatin silver print from around 1890 by the Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company. It’s quite striking for what’s essentially a cigarette card! What’s fascinating to me is how much it resembles an artistic photograph. What are your initial thoughts? Curator: It's interesting you call it 'essentially a cigarette card.' Think about that phrase. These cards were deliberately produced on a massive scale as premiums for Sweet Caporal Cigarettes. To me, this collapsing of ‘artistic photography’ into a commodity reflects broader late 19th century tensions: industry blurring the lines of art and commerce. Editor: That's a good point. The fact that it was made to promote something… does that change how we should appreciate the artistry? Curator: Not necessarily *change* how we appreciate it, but *frame* it. Who was Kinney Brothers employing, and how were they being paid? How were these prints circulated, consumed, and ultimately, discarded? We can ponder those relationships of production and consumption as well. Also, note the overt japonisme style in vogue. It suggests high taste, even if deployed through a low-brow medium. Editor: The Japonisme is obvious; almost every portrait from this time plays with similar stylized tropes. What else could this tell us about women and commercialism at the time? Curator: Well, consider the figure herself, an actress: her likeness *is* the commodity being circulated and consumed! Furthermore, such advertising created visual saturation—were consumers truly captivated, or did these images become visual noise, contributing to a growing indifference toward traditional aesthetics? Editor: I never thought of it like that, where mass production can numb appreciation! Thanks. Curator: Indeed! These ‘lowly’ artifacts often open up larger inquiries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.