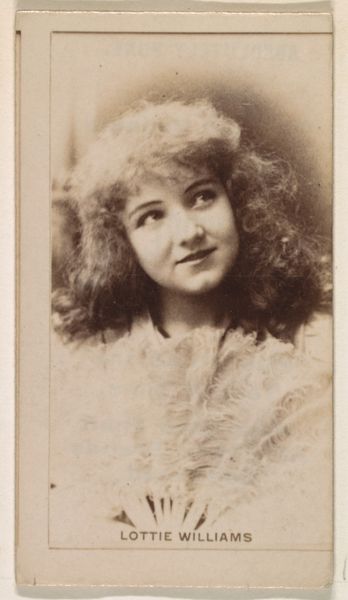

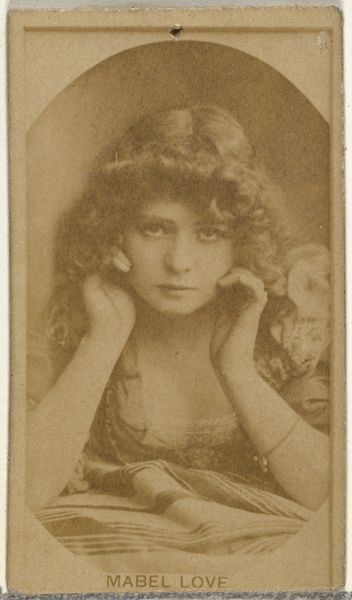

Mlle. Detchen, from the Actors and Actresses series (N145-8) issued by Duke Sons & Co. to promote Duke Cigarettes 1890 - 1895

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

photography

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 11/16 × 1 3/8 in. (6.8 × 3.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "Mlle. Detchen," an albumen print made by W. Duke, Sons & Co. sometime between 1890 and 1895, part of a series promoting Duke Cigarettes through images of actors and actresses. Editor: There's a captivating sepia tone that lends this portrait a melancholic air, don't you think? And the intimate scale – it feels like a glimpse into another time. Curator: Indeed. The albumen print was a very specific technology, where the paper was coated with egg white to create a glossy surface for the photographic emulsion. These cards were churned out in enormous quantities, a disposable piece of material culture meant to drive consumption. What strikes me is the mass production attempting to create individual appeal. Editor: Precisely! The subject isn't just Mlle. Detchen; it's the commodification of female performers and the burgeoning advertising industry. We're looking at the performance of identity within a capitalist structure. What power dynamics are at play here? Her slight smile, that suggestive glance - is this her choice, or manufactured consent? Curator: The labor conditions surrounding these print factories are worth exploring, too. The albumen process involved workers – mostly women, likely – handling hazardous chemicals. We have to consider their exploitation, their exposure. Was there a trade union presence influencing work conditions at Duke? Editor: It certainly prompts reflection on labour, visibility, and gendered expectations of beauty. How do we contend with the legacy of these images, understanding they existed for such capitalistic and often exploitative ends? Curator: It underscores the value we place on artifacts themselves, despite the often obscured labor processes. Thank you. It is essential to look at these everyday prints critically, asking questions not only of what is represented, but how it was created, and who it served. Editor: Yes, the ways we understand a single photographic artwork change vastly once situated within that context. I’ll carry these points forward in how I experience the portrait and the legacy of representation within image making today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.