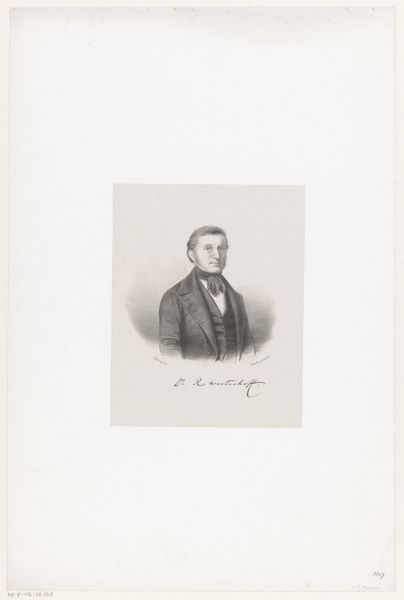

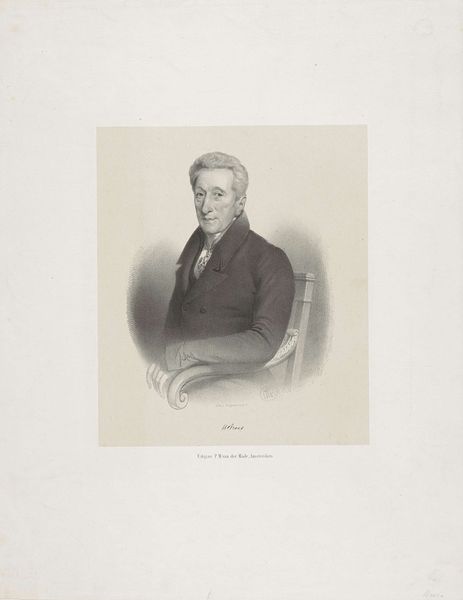

Portret van de dichter en predikant Jan Jacob Lodewijk ten Kate 1866

0:00

0:00

edouardtaurel

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

single portrait

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 202 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Edouard Taurel's "Portret van de dichter en predikant Jan Jacob Lodewijk ten Kate," created in 1866. It's a drawing, I think graphite or pencil. It has a rather formal, almost photographic feel, for a drawing. What strikes you about it? Curator: Well, let's think about the materiality itself. This isn’t simply a ‘drawing’; it’s a print based on a drawing. The labor involved in its production is already distanced – we're seeing a copy, a mass-reproducible image. What implications does that have? How does it relate to ideas of authenticity and value that were circulating then? Editor: That’s fascinating, I hadn't considered that. So, the 'original' drawing, which we can't see, gets transformed through a printing process, becoming available to potentially many more people. Did that democratization change how portraits functioned in society? Curator: Precisely! Think about the social context of the 1860s. Photography was emerging, threatening traditional portrait painting. This printed portrait exists in a strange space between handmade and mechanically reproduced images. And note the poet's clothing and what appears to be a decoration on his lapel. What might those signify? Editor: I guess it represents a specific form of labor, like his status or profession…the decoration perhaps awarded for his accomplishments. Was the purpose to memorialize him through this affordable format? Curator: Exactly. These printed portraits become commodities, circulating within a specific social sphere. How does the availability and distribution of these kinds of images reflect power relations and the creation of celebrity at the time? And what might that faint signature at the bottom suggest about authorship and value? Editor: It adds a personal touch to the copy. It's been interesting thinking about art not as a standalone piece, but in its material context. Curator: Indeed. By looking at the processes of making and distribution, we can understand how art reflects the values of its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.