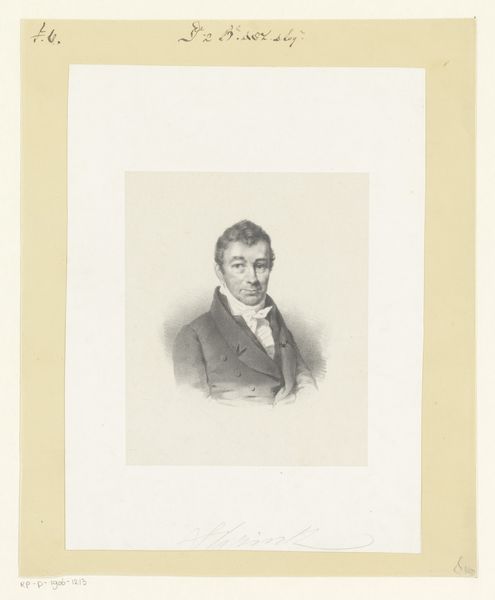

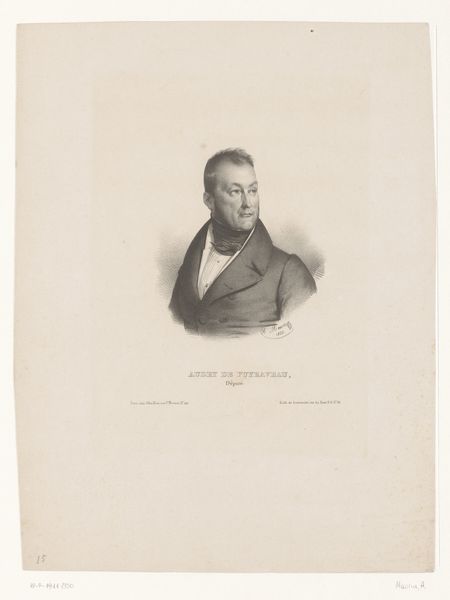

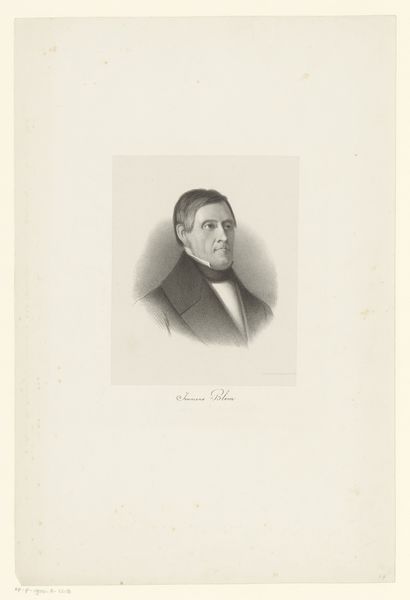

Portret van Antoni Christiaan Wynand Staring van den Wildenborch 1822 - 1845

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

#

photo restoration

#

parchment

#

light coloured

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 528 mm, width 351 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a drawing called "Portret van Antoni Christiaan Wynand Staring van den Wildenborch," dating from between 1822 and 1845 by an anonymous artist. It's a graphite and pencil drawing on paper. The light pencil work gives the piece a sort of delicate, aged feel. What stands out to you when you look at this piece? Curator: This portrait, though seemingly simple, offers a glimpse into the social and cultural values of its time. We must ask ourselves: who was considered worthy of representation, and what purpose did these images serve? The subject's pose, attire, even the subtle expression – they all speak to the sitter's status and role within the social fabric. Who was Antoni Christiaan Wynand Staring, and how does his portrait reflect the power dynamics of 19th-century society? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered the sitter himself as part of the meaning. Is the act of portraying someone automatically a statement of power? Curator: Precisely. Portraits, particularly during this period, were often commissioned by or for those in positions of power or influence. They served not only as records of appearance but also as tools for constructing and reinforcing social hierarchies. The very existence of this portrait suggests Staring's participation in, and affirmation of, a certain social order. Can we explore how class and status intersect with artistic representation in this work? Editor: So, looking at the drawing style itself, its realism… that was also part of projecting an image of someone respectable? Curator: Absolutely. The academic realism speaks to a desire for accuracy and truth, but we must remember that "truth" is always mediated through the artist's eye and the social context in which they operate. The very choice of realism, its connection to Enlightenment ideals and scientific objectivity, becomes a statement itself. How do you see the portrait engaging with contemporary ideas of identity and representation? Editor: I see now how much more there is to consider than just the likeness itself. Thanks for opening my eyes to all these different layers of context. Curator: And thank you for bringing fresh eyes to this portrait! It's through these kinds of dialogues that we can keep interrogating art's role in reflecting and shaping our understanding of the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.