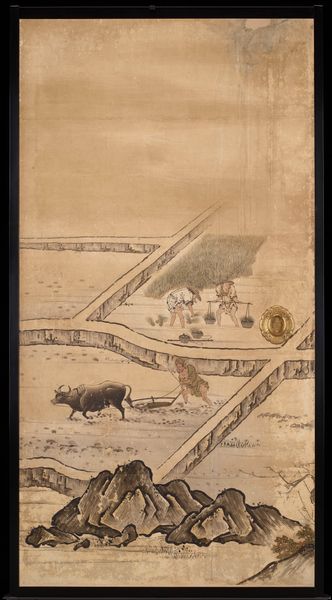

![Fall [center left from the set Rice Farming in the Four Seasons] by Kano Sanraku](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzFkMGE2NWFkLTUzODEtNDE5OC1hODQ3LTUyOGY1Y2IzNGQ4MC8xZDBhNjVhZC01MzgxLTQxOTgtYTg0Ny01MjhmNWNiMzRkODBfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

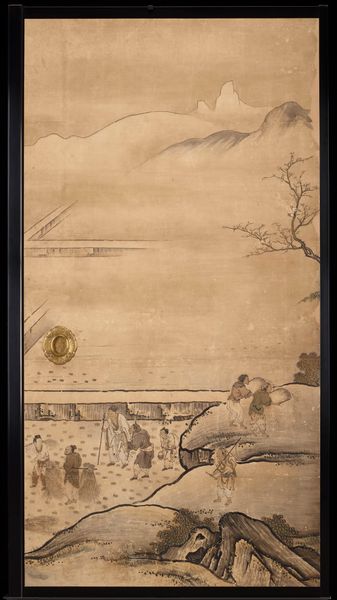

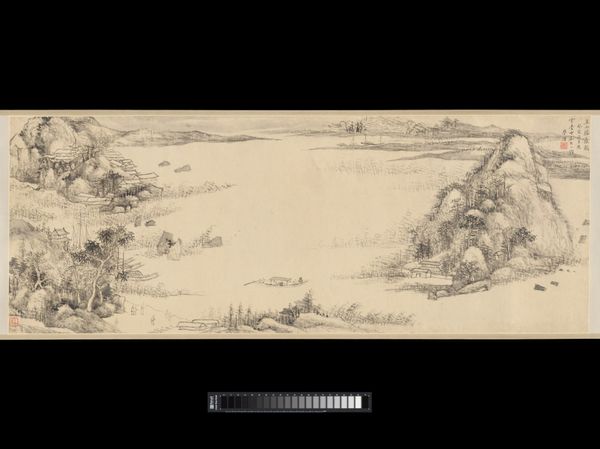

Fall [center left from the set Rice Farming in the Four Seasons] c. 1620s

0:00

0:00

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

ink painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

etching

#

ink

#

line

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 76 x 39 1/4 x 4 in. (193.04 x 99.7 x 10.16 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

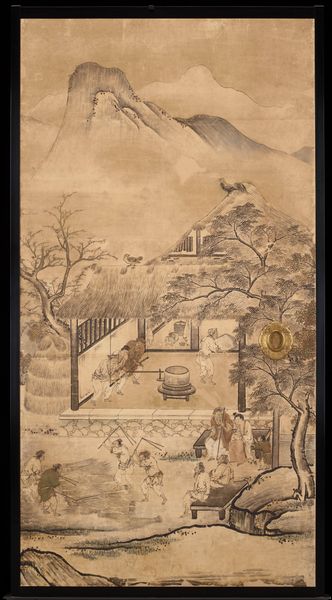

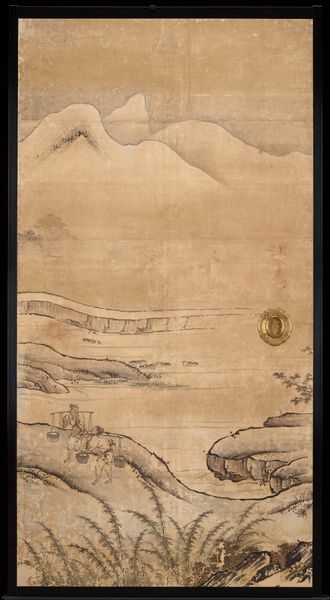

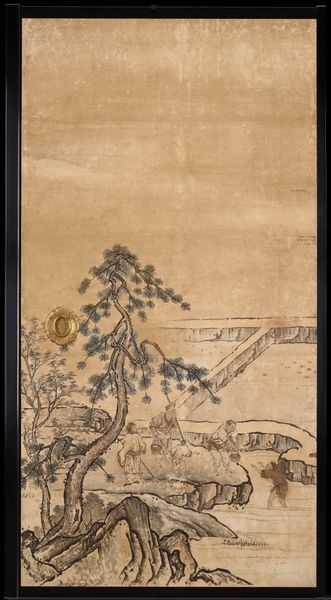

Curator: Before us hangs "Fall," one panel from the set "Rice Farming in the Four Seasons" created around the 1620s by Kano Sanraku. This ink drawing offers a glimpse into the cycle of agricultural life in Japan. Editor: It strikes me as beautifully sparse, almost melancholic in its tonality. The ochre paper support dominates the overall composition. Curator: It's compelling how Sanraku, amidst the changing political landscape of early 17th-century Japan, anchors his artistry in scenes of labor, celebrating a kind of agrarian stoicism. Consider the fraught dynamic between the increasingly urbanized samurai class and the rural farmers at this moment. Editor: And the visual balance Sanraku achieves here is extraordinary, wouldn't you agree? The careful placement of figures, the geometry of the paddies; see how the parallel lines lead the eye, establishing a formal cadence. It’s almost like a dance. Curator: The choice to depict labor—planting, harvesting—offers a poignant comment on the social hierarchy, reflecting the exploitation that fueled the upper classes, while upholding the peasant farmer as the ethical bedrock of society according to Confucian values. This creates a space for contemporary dialogue surrounding labor rights. Editor: Indeed, that geometric precision you mention lends structure but simultaneously it serves the composition as a powerful perspective tool, drawing the eye into a scene teeming with action. Curator: There’s an embedded commentary about land, power, and who controls these vital resources, echoing debates relevant today. The artist isn't merely painting a landscape; he’s interrogating a whole system. Editor: What an insightful and engaging examination, allowing for a broader contextual understanding. Curator: I'm left reflecting on art’s enduring ability to act as both mirror and magnifying glass, capturing societal complexities that resonate across time.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

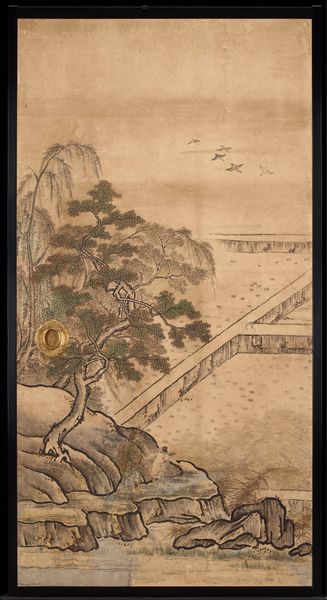

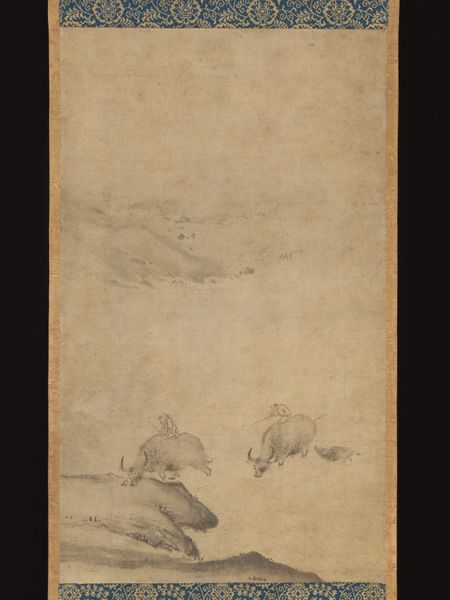

These sliding screens originally formed the four walls of a small reception chamber in Daikakuji, a temple in northwest Kyoto that alternately served as the palace for Japan's emperor. Representing the various activities associated with rice cultivation, the screens form a continuous agricultural panorama from wall to wall. Some of these chores include plowing, transplanting the rice, irrigating, threshing and grinding. Typical of paintings by artists of the Kano school, the theme derives from China and is didactic in nature. Agriculture, according to Chinese Confucian teachings, is the basis of a well-ordered society. Accordingly, when Japanese rulers adopted Confucianism as their ruling ideology, they also commissioned paintings which reflected social stability, morality and government values.Although unsigned, it is likely that these paintings are by Kano Sanraku who was commissioned to decorate the temple where these screens once existed. As head of the Kano school in the early 17th century, Sanraku evolved a style characterized by greater naturalism and detail than previous Kano artists. In addition to these characteristics, these screens exhibit a clear compositional arrangement, crisp brushwork, and heavily outlined rock formations--all hallmarks of the Kano style.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.