![Fall [right from the set Rice Farming in the Four Seasons] by Kano Sanraku](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzg1NjRhZDZhLWYxM2QtNDhiOS1iMTJkLTFiODI1N2EyNWI5YS84NTY0YWQ2YS1mMTNkLTQ4YjktYjEyZC0xYjgyNTdhMjViOWFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

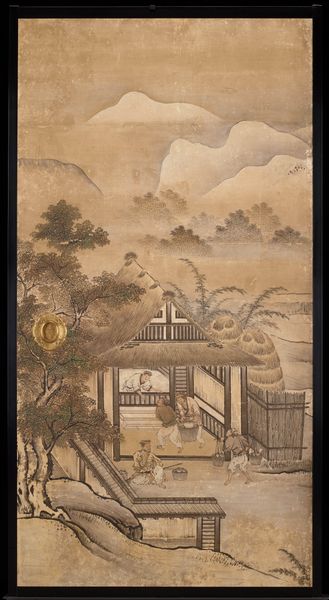

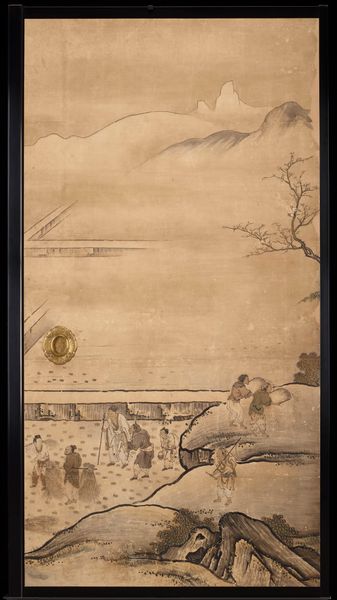

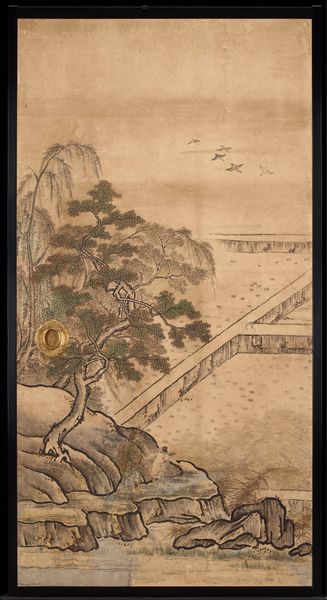

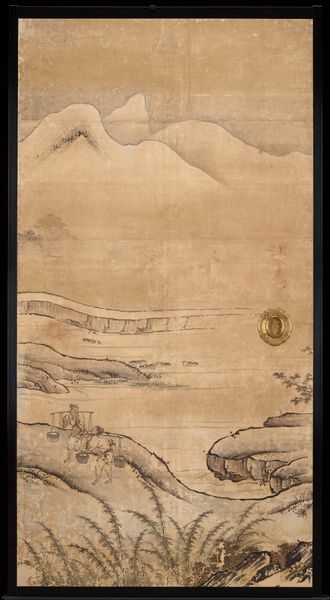

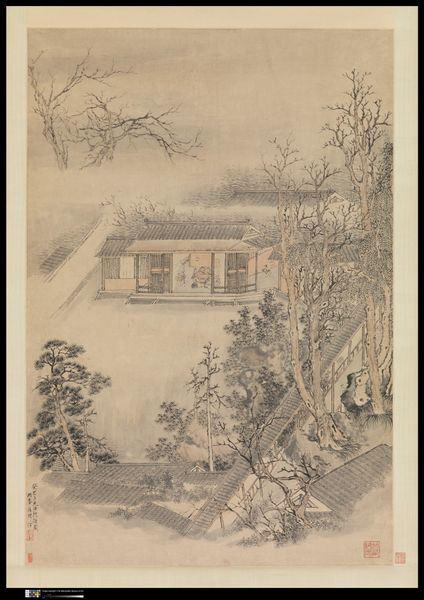

Fall [right from the set Rice Farming in the Four Seasons] c. 1620s

0:00

0:00

painting, ink

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

ink painting

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

Dimensions: 76 x 39 1/4 x 4 in. (193.04 x 99.7 x 10.16 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

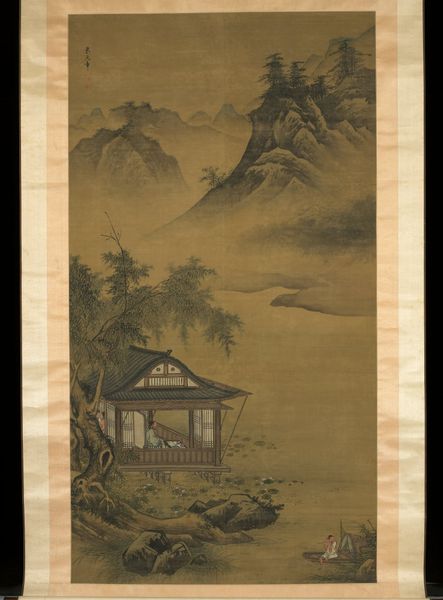

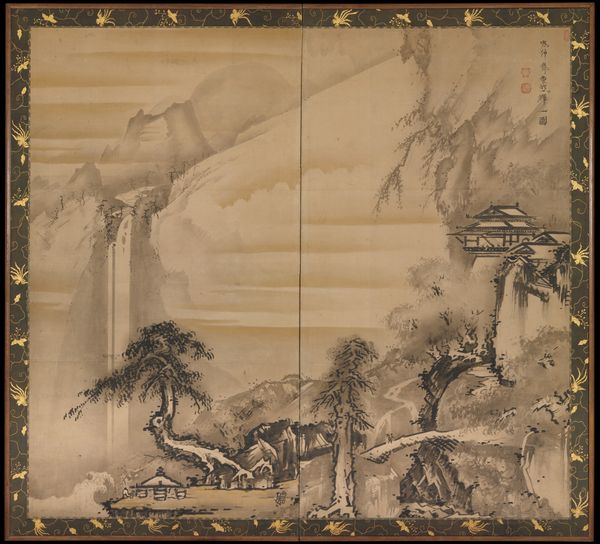

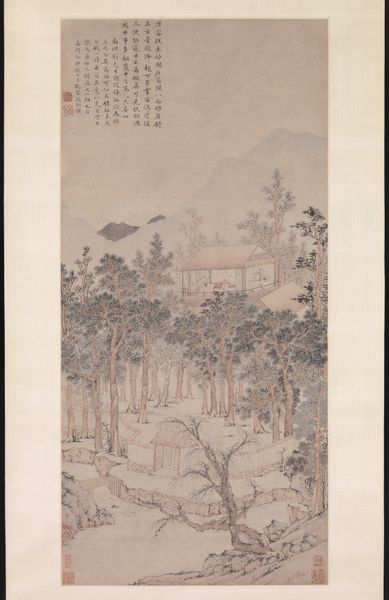

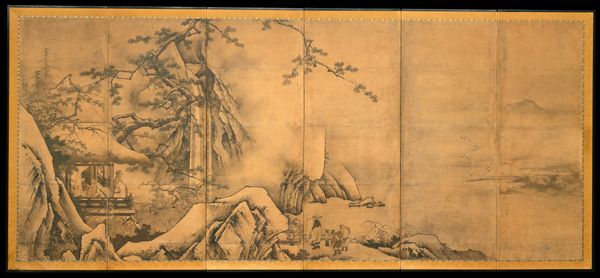

Editor: Here we have Kano Sanraku’s “Fall [right from the set Rice Farming in the Four Seasons]” from around the 1620s, currently residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The ink painting presents a vibrant autumnal scene, but it feels very...ordered. Almost staged. What do you see in this piece, particularly beyond its aesthetic qualities? Curator: This isn't just a landscape, it's a window into the socio-economic structure of 17th-century Japan. Sanraku, working within the Kano school, often served the elite. How does this imagery of seemingly idyllic rural life serve those power structures? Consider the romanticization of labor, the way hierarchy is subtly embedded, for instance with those reclining while others labor. Editor: I didn't consider that. I was focused on the harmony of it all, the balance between the landscape and the figures. Curator: And who benefits from this 'harmony'? Think about the farmers, who were a crucial yet often disenfranchised segment of society. By depicting them in a peaceful, productive manner, Sanraku's painting may gloss over the harsh realities they faced. It also helps cement idealized social hierarchies of the time, right? What do you think about that relationship? Editor: So, it's a beautiful image that might be upholding existing inequalities through its artistic choices. I see what you mean. The very act of depicting rural life this way is already a political decision, not a neutral one. Curator: Precisely. Art never exists in a vacuum. This piece allows us to explore critical questions about labor, power, and representation during the Edo period. Editor: That definitely adds another layer to how I understand the painting. Curator: Indeed. It is imperative to be aware of context. Thank you, it has helped me appreciate more layers in Kano Sanraku's approach.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

These sliding door panels originally formed the four walls of a small reception chamber at Daikakuji, a Buddhist temple in northwest Kyoto that also served as the palace for Japan’s emperor. The panels form a continuous panorama from wall to wall and present various activities associated with rice cultivation: plowing, transplanting the rice, irrigating, threshing, and grinding. The didactic theme is derived from Chinese painting; agriculture, according to Confucian teachings, is the basis of a well-ordered society. Accordingly, when Japanese rulers adopted Confucianism as their ruling ideology, they also commissioned paintings that reflected social stability, morality, and government values. Although unsigned, these paintings were likely produced by Kano Sanraku. As head of the Kyoto branch of the influential Kano school, Sanraku counted several prominent aristocratic families and Buddhist monasteries, including Daikakuji, as key patrons.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.