![Winter [center left from the set Rice Farming in the Four Seasons] by Kano Sanraku](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzhmY2MxYmI2LWU4NDctNDQwZC1hM2U3LTJjYTI2NzI2YmRjYi84ZmNjMWJiNi1lODQ3LTQ0MGQtYTNlNy0yY2EyNjcyNmJkY2JfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

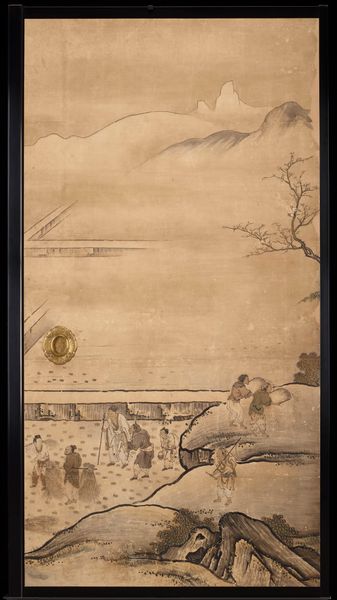

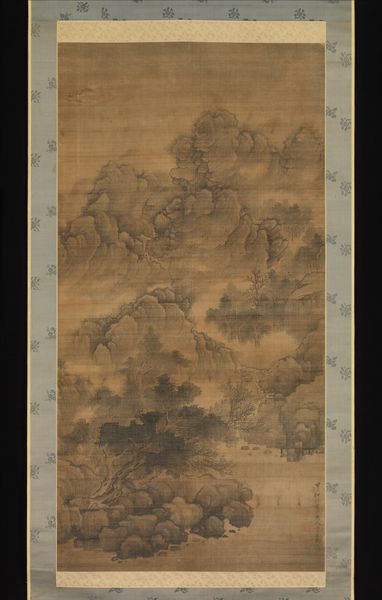

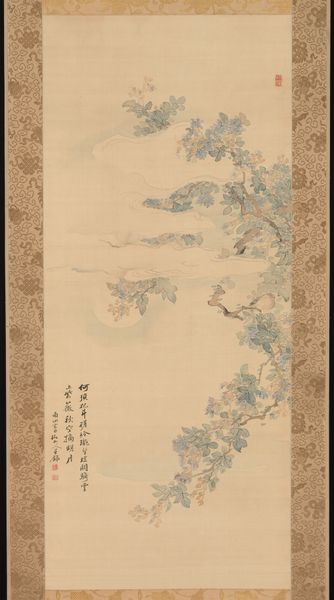

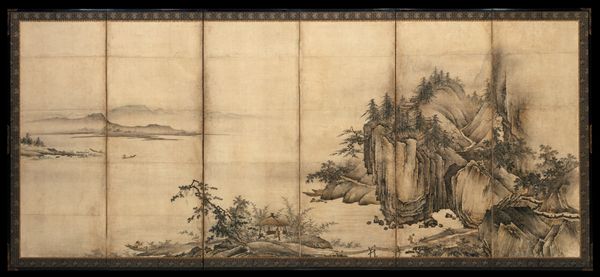

Winter [center left from the set Rice Farming in the Four Seasons] c. 1620s

0:00

0:00

painting, ink

#

medieval

#

ink painting

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

Dimensions: 76 x 39 1/4 x 4 in. (193.04 x 99.7 x 10.16 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: I’m struck by the pervasive sense of quietude emanating from this image. It's as though the very air is still. Editor: Precisely. What we’re observing is “Winter,” from the set “Rice Farming in the Four Seasons,” crafted by Kano Sanraku around the 1620s. This ink painting, currently housed here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, offers us a glimpse into 17th-century Japanese life and aesthetics. Curator: It's intriguing how stark and understated the imagery is; almost meditative, and at odds with our current conceptions of pre-modern or medieval existence. It’s monochrome and minimal. Editor: Indeed, the ink on paper medium lends itself to the subtle gradations we see here. Notice the visual weight given to the mountains looming distantly and the active figures struggling uphill, juxtaposed and intertwined, they establish the painting's narrative and thematic foundations, connecting humans and landscapes to nature’s endless cycles. Curator: Absolutely. In Asian art, mountains carry significant symbolic weight, representing stability and endurance. The rice farmers down below, bent under their loads, are rendered with remarkable humanity, reflecting the labor and persistence of agrarian society, so connected to these mountainous heights. They evoke, at least for me, enduring archetypes. Editor: And it's crucial to note the historical context. Kano Sanraku belonged to the Kano school of painting, a dominant artistic force in Japan for centuries. Their art served as political and ideological propaganda to assert power relations, class divisions, and moral values by painting idealized depictions of rulers, warriors, and mythical-historical heroes and narratives. Curator: Given the potential propagandistic applications you mention, this ink painting departs from expectations of what courtly artwork "should" communicate and present through landscape and figuration, yet this winter landscape does not hide its laborers at work, instead emphasizing their activity. Editor: This particular scroll speaks to a period where depictions of everyday life found their place alongside more traditional subjects. Curator: As such, we encounter the humanizing of the landscape and life within it in visual form. Food cultivation is part and parcel of larger concerns with life and labor and what it means to occupy land. Editor: Agreed, and spending this moment with this artwork reminds me of how art's meaning continuously shifts according to different eras. Curator: Indeed. The enduring relevance of "Winter" invites ongoing dialogue about life in nature.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

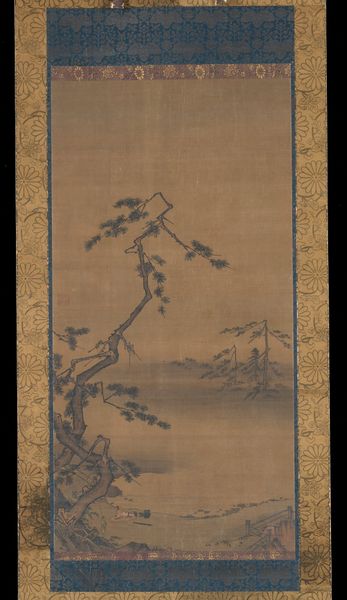

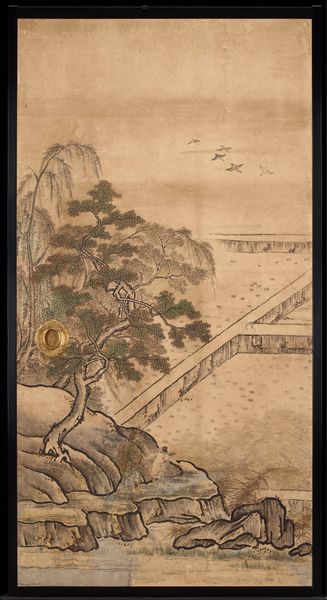

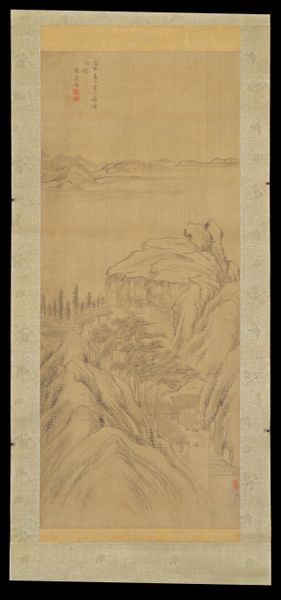

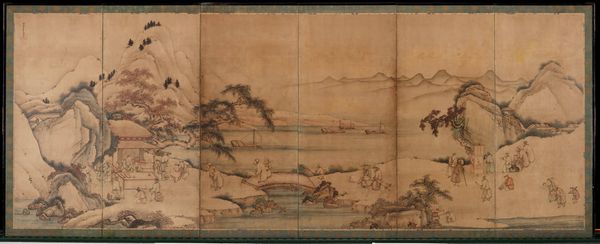

These sliding door panels originally formed the four walls of a small reception chamber at Daikakuji, a Buddhist temple in northwest Kyoto that also served as the palace for Japan’s emperor. The panels form a continuous panorama from wall to wall and present various activities associated with rice cultivation: plowing, transplanting the rice, irrigating, threshing, and grinding. The didactic theme is derived from Chinese painting; agriculture, according to Confucian teachings, is the basis of a well-ordered society. Accordingly, when Japanese rulers adopted Confucianism as their ruling ideology, they also commissioned paintings that reflected social stability, morality, and government values. Although unsigned, these paintings were likely produced by Kano Sanraku. As head of the Kyoto branch of the influential Kano school, Sanraku counted several prominent aristocratic families and Buddhist monasteries, including Daikakuji, as key patrons.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.