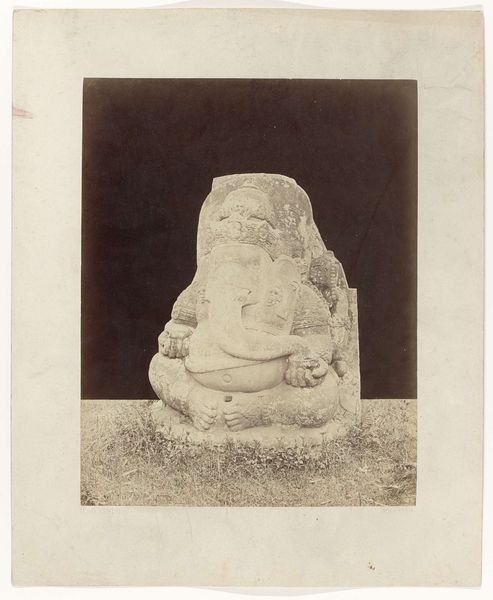

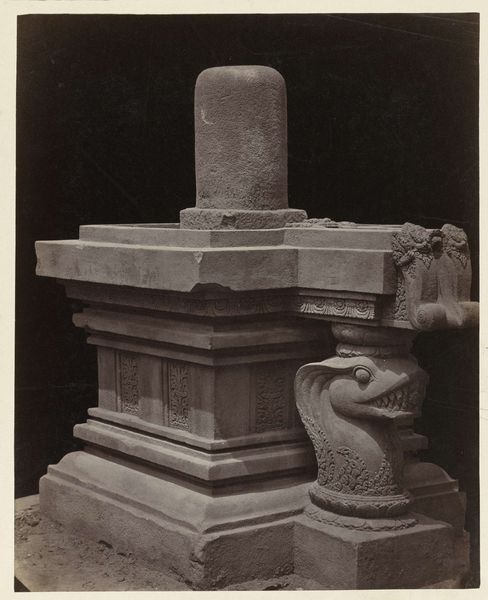

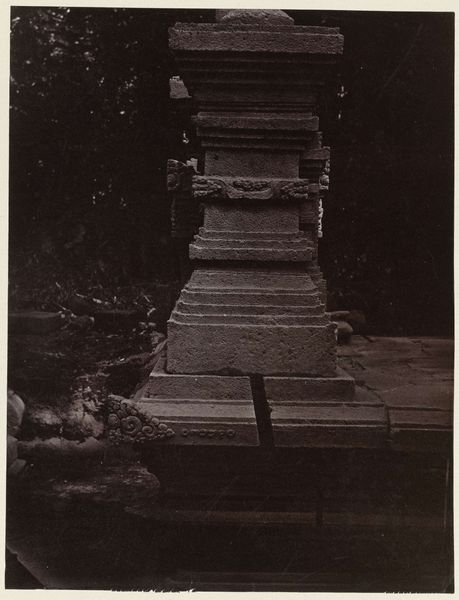

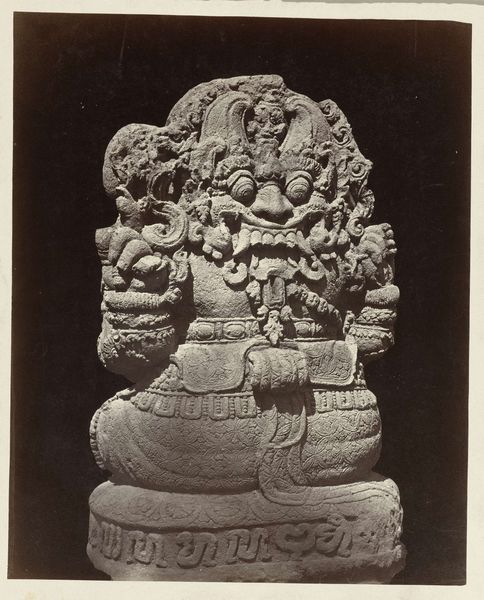

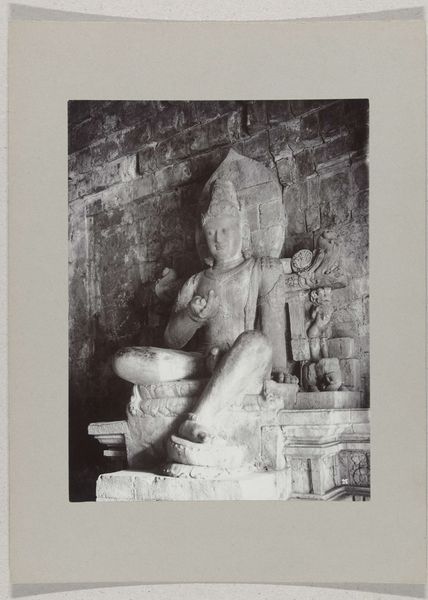

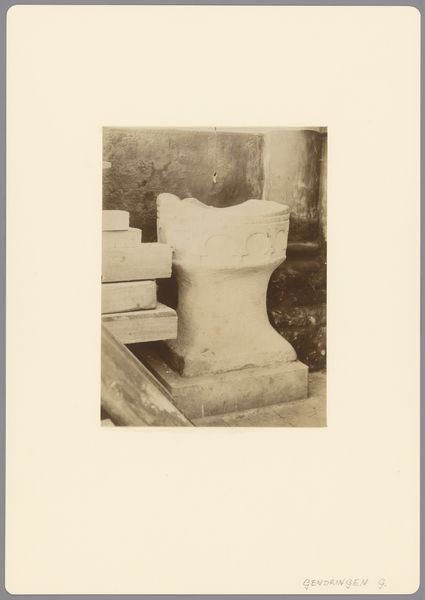

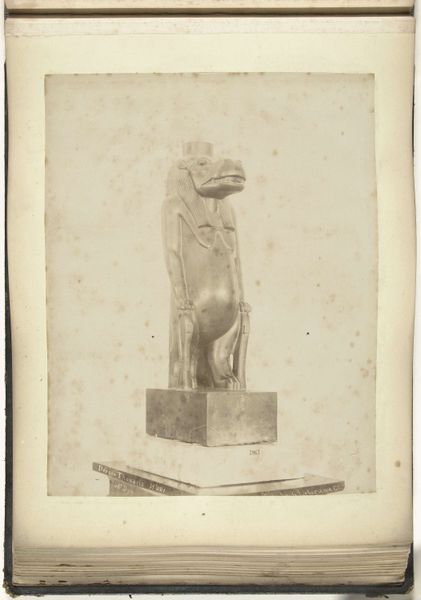

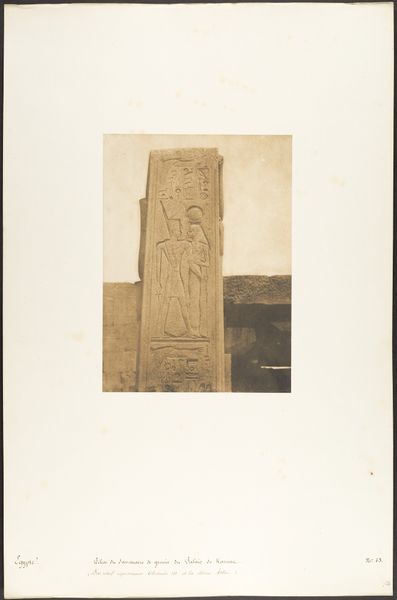

Inscribes slab (Old Javanese language, East Javanese Kawi script) from Candi Lor with a kalamukha on top (rear view); three statuettes (Surya, Nandi, femal dification imade), Residential house. Kediri, Kediri district, East Java province, 900-910 AD. Possibly 1866 - 1867

0:00

0:00

carving, photography, sculpture

#

carving

#

sculpture

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

carved

Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 240 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

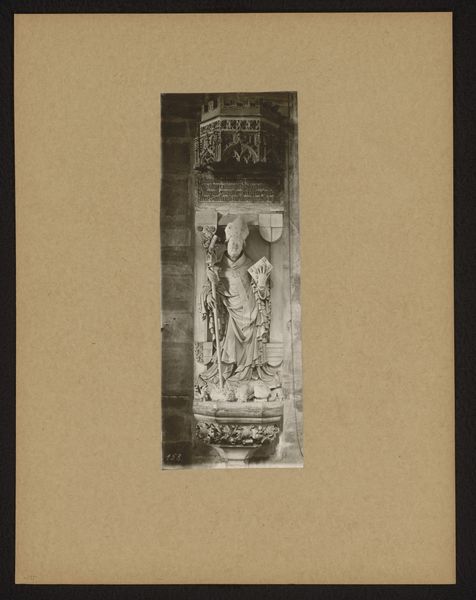

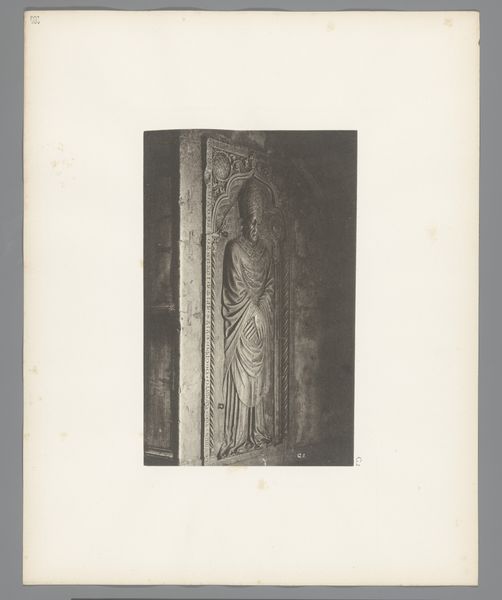

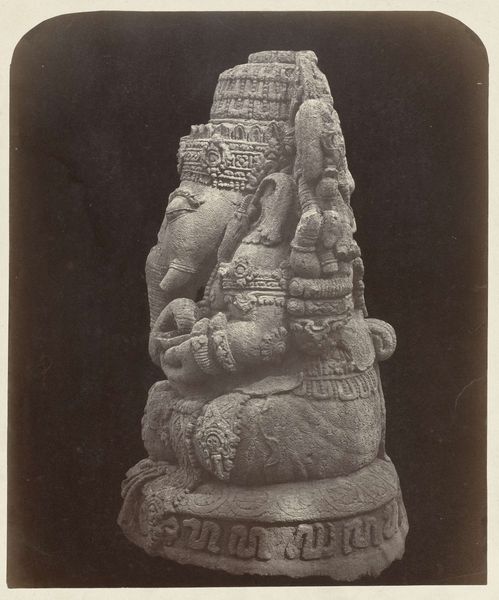

Curator: This image presents an inscribed slab dating from 900-910 AD, originating from Candi Lor in East Java. It’s captured here in a photograph, presumably taken in the late 19th century, alongside a few statuettes. Editor: It looks like it’s made from some kind of stone, probably locally sourced given its context. There’s a certain monumentality to the slab and the statuettes, despite their weathered state. What draws your attention to this particular arrangement of objects? Curator: Consider the labour embedded in the creation of these objects. The quarrying, the carving – each mark is a testament to human effort, and a relationship to natural resources and their manipulation into this slab with East Javanese Kawi script, and these representations of Surya, Nandi, and what looks like a female deification. The photography itself transforms the physical reality, recontextualizing it as an object for a different kind of consumption, accessible to a wider audience through its mechanical reproduction. Editor: So you see the photograph not just as documentation, but as another layer of material engagement? How might the context of 19th-century photography and archaeological study of Java inform that engagement? Curator: Precisely. Kinsbergen, the photographer, was working within a colonial structure that framed these artifacts as both historical relics and resources for knowledge production. Think of the photographer's intervention through staging this array of objects in relation to the natural setting and his process of illuminating them to emphasize texture and form. It all speaks to the broader cultural forces at play in shaping our understanding and perception of ancient Javanese society. The placement seems intentional; were these statues always next to the slab, or were they moved for the sake of composition, to become resources for colonial power? Editor: It's amazing to consider the many layers of "making" – from the carving of the stone itself to the creation of the photographic image. I will never look at historical documents the same. Curator: Exactly, it's the materiality that ties it all together: stone, script, photographic chemicals, each contributing to the artwork’s extended life and meaning through layers of production and reception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.