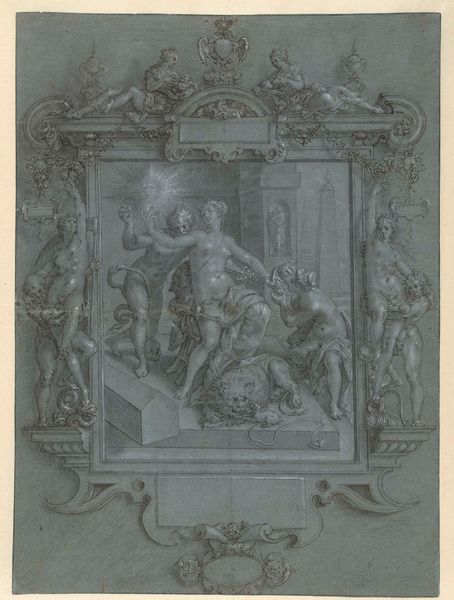

Ontwerp voor titelpagina voor Algemene Historie van het begin der wereld af, deel XIII, 1747 1747

0:00

0:00

jancasparphilips

Rijksmuseum

drawing, etching, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

narrative-art

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

classicism

#

pen

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

miniature

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Jan Caspar Philips’ "Ontwerp voor titelpagina voor Algemene Historie van het begin der wereld af, deel XIII," dating from 1747. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by how busy the composition is, a framed tableau layered with historical figures and decorative elements. The monochromatic palette gives it a somewhat solemn air. Curator: Indeed. Philips produced this as a design for the title page of a historical work, and it is full of allegorical figures, classical architecture, and coin portraits of emperors. Note how these visual cues reinforce the book’s authority. Editor: You can really see the layered approach to production. Pen, ink, etching, drawing. All suggesting meticulous labor. What was Philips’ role in the printmaking community? Was he renowned? Curator: Philips was part of a network of engravers, illustrators, and publishers during the Enlightenment. Prints like these weren’t merely decorative. They visually anchored narratives, disseminating historical knowledge while subtly promoting the values of the period. Editor: I see it! It’s more than just illustration; it's the manufacturing of history itself! What do you make of that scene within the architectural frame? The sacrificial fire, the prostrate figures. Curator: The scene is a classical history tableau, very much of the “history painting” tradition of the era. The ritual and supplicants suggest a plea to the past for insight or legitimation. Consider how the classical style reinforced ideals of order, reason, and civilization that were core to the era. Editor: Yes, a sort of validation through aestheticized historical framing. I’m pondering on what these designs meant for the common person consuming them at that time? Were they for the elite or intended to percolate down the societal echelons? Curator: Broad accessibility was a key function. While luxury versions existed, printed material had growing circulation in society; affordable prints, influencing public perceptions of the past and, consequently, present political ideas. Editor: Seeing the making and labor really highlights that impact, almost like a factory turning the raw ore of the past into gleaming ideological coins. Curator: Exactly. Philips’s piece allows us insight into that relationship—the historical, political, and artistic forces behind knowledge production. Editor: And to trace its social construction in materials and labor...it really makes you think about the many hands involved. Thanks for bringing that to light!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.