Dimensions: image: 450 x 582 mm

Copyright: © Thomas Struth | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

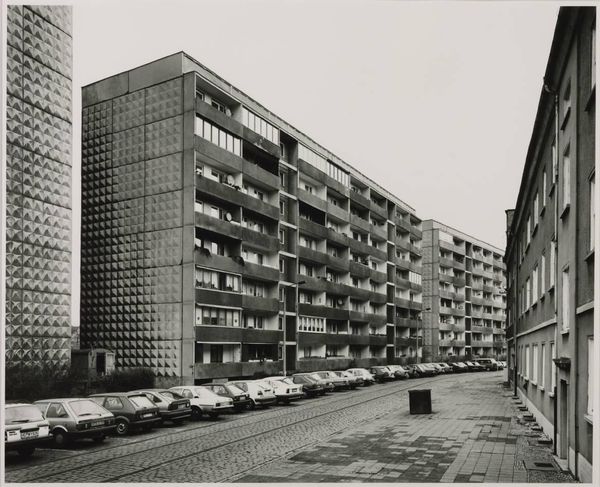

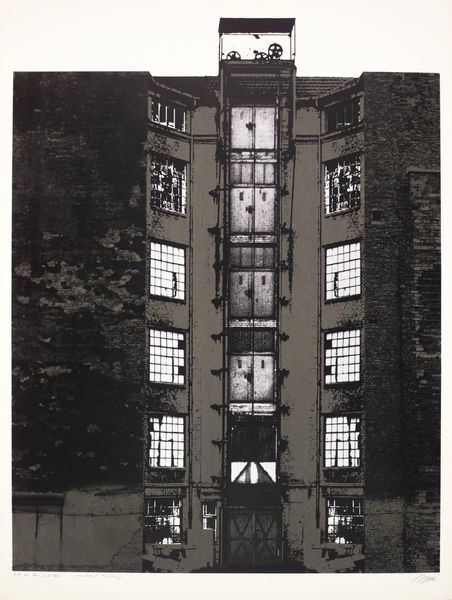

Curator: This is Thomas Struth's "Hermannsgarten, Weissenfels 1991," a photograph held in the Tate Collections. What do you make of it? Editor: Bleak, but with a strange, quiet beauty. It reminds me of those old black and white photos of industrial towns. It looks like a place where time stopped. Curator: Indeed. The symmetrical composition, the aging buildings, even that odd aerial tramway—they evoke a very particular moment in German history. The image captures that feeling of in-between-ness after reunification. Editor: The tramway almost looks like a forgotten symbol, a relic of some outdated technology or ideology. The cars below are also period specific. Curator: Precisely. Struth often explores how history shapes our urban landscapes, and through them, our collective memory. Editor: It definitely makes you think about what stories these buildings could tell. Curator: It’s an invitation to imagine the layers of lives lived within these walls. Editor: And how those structures persist, carrying forward echoes of the past.

Comments

tate 9 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/struth-hermannsgarten-weissenfels-1991-p20158

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 9 months ago

⋮

Thomas Struth began taking photographs of industrialised cities when he was studying under Bernd Becher (born 1931) at the Düsseldorf Academy in the late 1970s. He has continued to explore and develop the theme for almost twenty years, focusing his attention on such cities as New York, Tokyo, Berlin and Naples. Since the mid 1980s he has also produced landscapes, portraits and photographs of visitors in museums. Struth's images of the urban environment concentrate on seemingly unspectacular streets and public spaces. He seeks to record the face of urban space, seeing the architectural environment as a site where a community expresses its history and identity. In interviews he has stated that his images aim to explore what public spaces 'might say about the people who live in these sites.' (Quoted in Gisbourne p.5.) In recording the urban environment, Struth deliberately refers to the tradition of black and white documentary photography, adopting a seemingly objective position. The compositions are simple and the photographs are neither staged nor digitally manipulated in post-production. Struth has said: 'for me it is more interesting to try and find out something from the real than to throw something subjective in front of the audience.' (Quoted in Minelli p.190.) However, in spite of a link to the reportage tradition, Struth avoids both its snapshot approach and its quest for the capture of a fleeting, spontaneous image. Rather he carefully selects the sites where, using long exposures he makes sharply focused images. In 1991, two years after the unification of East and West Berlin, Struth began working on an extensive series of images that sought to record the face of the former East Germany, (of which Tate owns five). He travelled the country, taking photographs in a variety of cities which had previously been inaccessible from the West. In Hermannsgarten, Weissenfels 1991 Struth employs techniques which have characterised the street scenes since the 1970s. He places the camera in the centre of the street at eye level, creating a vertiginous one point perspective that leads the viewer's eye past the severe nineteenth century apartment buildings to the end of the street. Serried ranks of windows punctuate the brick facades. A few cars, a dustbin and a pile of sand can be seen on the pavement. Cables and streetlights hang between the buildings in the overcast sky, yet there are few traces of the domestic lives of the inhabitants. Struth avoids all human activity and incident so that the deserted street appears like an empty stage-set. The central focus of the photograph is an empty space. The image has a melancholic atmosphere of absence, a mood which is enhanced by the neutral grey light of early morning that bathes the scene. The slightly shabby East German world that Struth depicts is one in which time is presented as having stood still. It is a world that is at once recognisable, but also alien because it had been hidden from Western eyes for forty years. It is an image of a world in which time has stood still. The uninflected image gives no hints as to how it is to be interpreted, and the viewer is led to linger over what might otherwise seem an un-noteworthy, everyday vista. As Struth has said, his work is intended to 'give pause', and thus resist immediate consumption. He seeks to bring about a 'move to investigative viewing' which is also a 'call to interact.' (Quoted in Buchloh p.31.) Further Reading: Mark Gisbourne, 'Struth', Art Monthly, no.176, May 1994, pp.3-9Giovanna Minelli, Another Objectivity, exhibition catalogue, Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Paris 1989, pp.189-194Benjamin Buchloh, Portraits: Thomas Struth, exhibition catalogue, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York 1990Thomas Struth, 'Photographs from East Germany', October, no.64, Spring 1993, pp.34-55, reproduced p.41 Imogen Cornwall-JonesJuly 2001